I. Introduction to Monopolies

advertisement

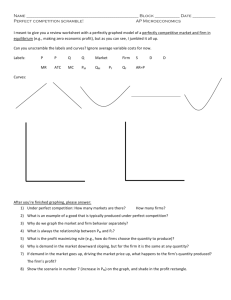

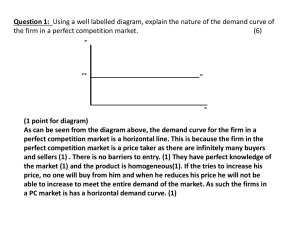

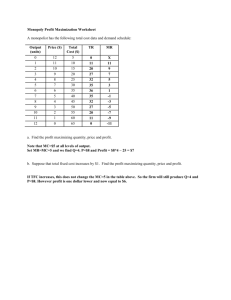

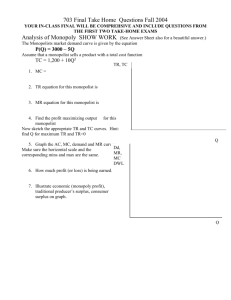

University of Pacific-Economics 53 Lecture Notes #13 I. Introduction to Monopolies As we saw in the last lecture, an industry in which individual firms have some control over setting the price of their output is called an imperfectly competitive industry. Under perfect competition, firms had to accept the price that was set at the market. If perfectly competitive firms set their prices higher they would lose all demand for their product. Imperfectly competitive firms have the feature that they can raise the price of their product without losing all the quantity demanded. A. Characteristics of Monopolies Firms are said to be a pure monopoly if they have the following characteristics (1) The firm is the only seller in the industry (2) The product is unique (3) There exists barriers to entry into the industry B. Decision Process for a Monopolist We saw for firms in a perfectly competitive industry, the price was determined by the market, thus the only decision a firm could make was the level of output. Monopolists on the other hand have to choose both the output level and the price level that will maximize profits. Let’s do a quick review of a firm in a perfectly competitive industry. The market price for a good is determined by the industry (market) supply and demand curves. The point at where the two curves intersects will be where the equilibrium price will be. (This is illustrated in Figure 1(a). At the equilibrium price, the individual firm can sell as much output as it wants. The demand curve for a perfectly competitive industry is horizontal because if the firm tries to raise its price, the quantity demanded would drop to 0. The marginal revenue curve will also be horizontal. The reason why is that when a perfectly competitive firm sells one extra unit, the change in revenue will simply be the price of the good. Thus demand=P=MR which is illustrated in Figure 1(b). One key difference between a monopolists and a perfectly competitive firm, is that there is no difference between the monopolist and the industry. Since the monopolist is the only seller of a product the firm it is also the industry. Thus the downward sloping industry demand curve also happens to be the demand curve for the monopolist. One key similarity between a monopolist and a perfectly competitive firm is that the monopolist will maximize profits where MR=MC. Thus a monopolist will continue to produce output until the MR=MC. In fact for a monopolist, the MR curve will always be below the demand curve. The following example will illustrate these points. Example: Suppose that the Kiev Plutonium Factory is a monopolist in the production of Polonium 210 a radioactive substance used to assassinate spies. It faces the following demand schedule. Table 1 Price $60 $57 $54 $51 $48 $45 $42 Quantity 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Notice that although the monopolist can set its own price, it cannot charge any price it wants. Notice that any price above $60 will result in no demand for the product. Also note that unlike perfectly competitive firms, if the monopolist wishes to increase production and sell more output, it must lower the price of its product. Now using the definitions learned in previous chapters, we can calculate the total revenue and marginal revenue at each quantity level. This is shown in Table 2. Table 2 Price Quantity Total Revenue $60 $57 $54 $51 $48 $45 $42 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 $0 $57 $108 $153 $192 $225 $252 Marginal Revenue $57 $51 $45 $39 $33 $27 Figure 2: Total Revenue and Marginal Revenue $60 $50 Price $40 $30 Demand $20 Marginal Revenue $10 $0 0 2 4 6 8 Output Total revenue is just P x Q. Marginal revenue is the extra revenue generated by selling one more unit. Suppose the monopolist has producing 3 units of good and wanted to increase production to 4 units. The total revenue increases from $153 to $192. Thus the change in revenue due to the production of the extra unit of output was $39. The marginal revenue of the 4th unit was $39. It’s important to note that the marginal revenue of the 4th unit which is $39 is lower than the price at 4 units which is $48. Why is the marginal revenue lower than the price of the good? The reason why the MR curve is below the demand curve is that in order to increase sales, the monopolist must lower the price on all units sold since it faces a downward sloping demand curve. We’re assuming that the monopolist can charge only one price in the market (that is the monopolist can’t price discriminate-charge different prices to different customers). There are two effects when a monopolist cuts prices: (1) The firm gain revenue because it can sell more units (2) The firm loses revenue because the firm must lower the price for units it could have sold at a higher price. Going back to our example, we’ll look at the effects on revenue as the firm increases production from 3 units to 4 units. (1) If the firm was to sell the 4th unit, it would gain revenue from that 4th unit sold. The 4th unit could sell for $48 so the firm’s revenue would increase by $48. ∆TR = $48 (2) However, if the firm sells the 4th unit, it has to lower the price. Before the firm could have sold 3 units for $51 each. In order to sell the 4th unit, it has to lower the price of all the units. Thus the 3 units the firm could have sold for $51, they now sell for $48 as well. Thus the firm loses $9 in revenue because of this effect. ∆TR = -$9 The overall change in total revenue is $48-$9 = $39 which is the marginal revenue. It is this second effect that occurs when the monopolist cuts their prices that results in the marginal revenue curve being below the demand curve. Now that we know that the MR curve will be downward sloping, we can introduce our cost curves (the MC curve and the ATC curve) and see where the firm will produce. Figure 3 shows a hypothetical monopoly. Figure 3: Price and Output Choice for a Monopolist The monopolist will produce where MR=MC. In Figure 3 that is where the quantity=QM=4000. Look at what happens if the monopolist produces less than 4000 units. At low levels of production, the monopolist will find that MR>MC. In other words if the firm produces one more unit, the extra revenue generated will be greater than the cost of producing that good, thus the firm will earn a marginal profit. The monopolist would definitely want to produce more output. Likewise, if the quantity produced was above 4,000 units, the MR < MC. If the firm produces one more unit, the extra revenue generated will be less than the cost of producing the good, the firm will be losing money. The firm will cut back production. The firm will only stop when MR=MC. Now we know the output level the monopolist will produce at. How will the monopolist choose the price? Well the price is determined from the demand curve. We know the quantity, thus we go directly from the quantity to see where it intersects the demand curve (Point A). At Point A the price the monopolist will charge will be $4. Total revenue will be $4 x 4000 units = $16,000. What is total costs? We can see from Figure 3, that when production is at 4000 units, the average cost is $3 per unit (Point B). Thus total cost will be $3 x 4000 = $12,000. Total profits will be $16,000-$12,000=$4,000 which is also the shaded rectangle in Figure 3. Unlike the perfectly competitive firm, a monopolist will keep this profit even in the long-run. C. Monopoly Outcome vs. Perfect Competition Outcome Figure 4 shows our now familiar perfect competition outcome. Firms are price takers in the output market and equilibrium price is determined by the supply and demand curves of the industry. Firms will produce where MR (the demand curve) intersects the MC curve (Point A) In the long-run perfectly competitive firms will earn 0 economic profits so the minimum point of the ATC will also be at Point A. The perfectly competitive firm will charge the market price Pc and produce the quantity qc. Now consider what would happen if all the firms in the industry merged together to form a monopolist. In what ways would the monopoly situation be different from the perfectly competitive situation? Figure 5 shows that if the industry becomes a monopoly, the demand curve will be downward sloping. Point A represents the old perfectly competitive equilibrium. Notice that at Point A price is where demand is equal to supply (the marginal cost curve). We saw from Figure 4 that at Point A the price charged will be Pc and the quantity supplied would be qc. However, a monopolist will produce where MR=MC. In the monopoly situation, not only is the demand curve downward sloping, but so is the marginal revenue curve. The marginal revenue curve is below the demand curve. The monopolist will produce where MR=MC. At that point the monopolist will produce qm units of output. Going up we find the price associated with that level of output on the demand curve (Point B). At Point B, the price charged by the monopolist will be Pm. The shaded red area indicates that the monopolist also earns a profit. Figure 5 illustrates the 3 key differences between the monopoly outcome vs. the perfectly competitive outcome. • The monopolist will produce less output than the perfectly competitive outcome • The monopolist will charge a higher price than the perfectly competitive outcome • The monopolist will earn above normal (economic) profits in the long run D. Barriers to Entry As we saw in the last section one of the key differences between a monopolist and a perfectly competitive firm is that a monopolist can earn positive profits in the long-run. In the perfectly competitive case we saw that the existence of profits would lead to additional firms entering the industry in the long run which will increase supply and lower the price. In the long-run perfectly competitive firms can only earn zero economic profits. The fact that monopolists are able to maintain economic profits in the long run must be due to barriers to entry into the industry. We will now examine several of these barriers. 1. Economies of Scale Recall from Chapter 9, that economies of scale was defined as a situation where average costs decreases as production increases. We saw that firms should produce at the minimum efficient scale (MES) in the long-run to be competitive. MES is the minimum point on the LRAC curve. Firms that are not producing at that point have higher costs than other firms and will be at a severe disadvantage. Figure 6 illustrates the economies of scale for an industry Figure 6 Figure 6 shows that at production below 500,000 units the industry has economies of scale. That is to say that increasing output production will lower costs for firms. The optimal point for a firm is to be at the minimum of the LRAC which is at 500,000. A firm that produces at a smaller scale (Scale 1) with 100,000 units will face higher costs and will not be able to compete against the firms who are at Scale 2. Gaining scale however, is not easy in some industries. For example think about the electric industry. It takes vast resources to set up power poles, electric grids, etc but once the infrastructure is in place, the power company can provide electricity at low average costs (Scale 2). Think about another firm who wants to try to compete with PG&E. That firm would have to spend huge resources to set up its own electric grid and infrastructure. Initially, it could only produce a smaller amount than PG&E (Scale 1). But at that scale it wouldn’t be able to compete very long against PG&E whose costs are only $1 per unit of electricity while the start-up has average costs of $5 per unit. The start-up will soon find itself out of business and PG&E will be the only seller. Instances where economies of scale leads to only one firm in the industry is called natural monopoly. 2. Patents Another barrier to entry that leads to monopoly power is a government patent that gives a firm exclusive right to produce a product for 20 years. The ability of the government to issue patents was written explicitly in the U.S. Constitution. Patents provides incentives for firms to conduct research and innovation in the form of monopoly profits on the new product over the period covered by the patents. If the monopoly profits are large enough to offset the high research and development costs of a new product, a firm will develop the product and become a monopolist. Patents maybe be useful from a society’s perspective because it may encourage the development of products that otherwise might not have developed. Example: Suppose a pharmaceutical company is thinking about developing a drug called Flexjoint that will cure arthritis. They’ve done some research and determined that: • The economic cost of research and development will be $14 million (includes the opportunity cost of the project) • The estimated annual economic profit from a monopoly will be $1 million (in today’s dollars). • If Flexjoint is not protected by a patent, it will only take competitors three years to figure out the formula behind Flexjoint and will thus be able to produce their own competing drug. Thus the monopoly would only last three years. Based on these numbers, the pharmaceutical company won’t develop the drug unless the firm receives a patent for it. If they get a patent, they’ll be able to enjoy a $1 million annual profit as a monopoly for 20 years which will pay off the initial high R&D costs. 3. Government Monopolies There are examples when governments set up their own monopolies. The book provides a couple of examples. First and best known example are state lotteries. The state is the only seller of lottery tickets and thus enjoys above-normal economic profits. Many state governments are in the lottery business as it is an easy revenue source for their budget. 4. Ownership of a Source Factor of Production Obviously, if only one firm owns a critical factor of production to produce a good then only that firm will be able to produce that good. A good example are diamonds. You need to have access to diamond mines in order to produce diamonds. DeBeers Company of South Africa controls approximately 90% of the world’s diamond mines, and thus not surprising is the largest seller of diamonds in the world. 5. -etwork Effects Network effects (sometimes called network externalities) is the idea that the value of a product increases with the number of consumers who use it. One good example are video game consoles. Suppose a new video game console is being developed to challenge Nintendo, Xbox and Playstation 3. If only a few consumers purchase this new game console, there will be little incentive for software manufacturers to develop game titles for the new console. Thus the new game console will be of little value to the consumers who purchase it. Network effects provide an advantage to existing firms who have already built up a large network and may inhibit the entry of new firms. II. The Social Costs of Monopoly Why should society be concerned about the development of a monopoly? As we saw monopolies can use their market power to charge a relatively high price compared to a perfectly competitive firm. If that was the only effect, then the story would be about redistribution as a monopolist would gain at the expense of consumers. However, the social costs go beyond this. Monopolies causes inefficiency by producing less than optimal and reduces the size of the combined economic gain to consumers and producers (total surplus). A. Deadweight Loss from Monopoly In Chapter 4 we introduced some concepts that were used to measure efficiency: consumer surplus, producer surplus and total surplus. Recall that consumer surplus is the difference between consumers’ willingness to pay and the price they actually paid. It is the area below the demand curve and above the price line. Producer surplus was the difference between the firm’s willingness to supply and the price they actually receive. It is the area above the supply curve and below the price line. Total surplus is just consumer plus producer surplus. If any of this is unfamiliar, you should do a quick review of Chapter 4. To make our graphical analysis much easier we’re going to assume that marginal cost and average total cost are constant. That is if we increase production of a good by one more unit it will have the same marginal cost and total cost. Figure 7 shows the monopoly situation with a constant marginal cost and average total cost curves. Point c reflects the perfectly compeititive case. Perfect competitive outcome would have been the production of 400 units of output at a price of $8. Under the perfectly comeptitive situation the consumer surplus would have been the entire triangle composing of Areas A+B+C. Using some simple geometry that area would be $16 x 400 x ½ = $3200. Now the presence of a monopoly means the monopolist would produce where its MR curve intersects the MC curve. This results in lower output (200 units) and higher price ($18) point b. What is consumer surplus now? Consumers now pay a price of $18, there are still some consumers who would have been willing to pay more than $18 and thus would have had consumer surplus (Area A) but as you can see the area of consumer surplus is smaller than before. Consumer surplus is now $6 x 200 x ½ = $600. The new monopoly would have a surplus. It would have been wiling to supply the good at $8, but now receives $18 for it. The area of producer surplus is $10 x 200 = $2000. This is also the area of producer profit. The producers gained at the expense of consumers since consumers had to pay $10 extra on the 200 doses resulting in a loss of $2000 for the consumers. However, note that the consumers had lost a total of $2600. Because the monopolist recoveres only part of the loss experienced by consumers there is a net loss from switching to monopoly. Consumers lose rectangle B and traingle D, but the monopolist only gain rectanble B. That leaves triangle D as the net decrease in the total surplus. This is the deadweight loss from monopoly. The deadweight loss comes about because the monopolist produces less output than a perfectly competitive market. The monopolist prevents consumers from getting surplus from consuming between 200 and 400 units and this creates inefficiency. B. Rent-Seeking Behavior Another social cost associated from a monopoly is the use of resources to maintain their monopoly power. As we know, monopolies can earn an economic profit as long as they can prevent new firms from entering the market. Firms are willing to spend money to persuade the government to erect barriers to entry that would prevent new entrants. As we saw in our last example, the monopolist was able to earn $2000 in above normal profits if new firms were able to enter the industry it would be reduced to 0 economic profits. Thus the firm would be willing to spend up to $2000 in lobbying efforts to protect its profits. Rent seeking is the process of taking actions to preserve economic profits. Rent seeking is a social cost, because it uses resources that could have been used in other ways. For example, the money spent on lobbyists a firm hired to protect its profits, could have been used to hire workers to actually produce goods and services. III. Price Discrimination Up until now we’ve assumed a monopolists charges the same price to all its customers. However, there are numerous examples of firms charging different prices to different individuals for essentially the same product. If a firm is able to divide customers into two or more groups and sell the good at a different price to each this is called price discrimination. In essence the firm has figured out that different groups have higher willingness to pay than others and will charge those groups a higher price. Here are some examples of price discrimination: • Discounts on Airline Tickets: Airlines often offer lower prices to fliers who stay overnight on Saturday because they are more likely to be tourists not business travelers. A typical tourist would not be willing to pay as much for air travel as the typical business traveler. Additionally, people who purchase tickets 14 days in advance will pay a lower fare than a person who purchase their tickets at the last moment. • Senior discounts on movie tickets: Which group would you think would have a higher willingness to pay to see the latest Hollywood blockbuster: Young adults or senior citizens? Theaters know that young adults are more likely to want to see the hottest new film, while seniors are more content to wait for the movie to come out on DVD. Thus they will charge a higher price to adults than to seniors. Price discrimination is legal as long as the firm doesn’t use it to drive rival firms out of business. A firm has an opportunity for price discrimination if the following conditions are met. 1. Market Power: The firm must have some control over its price. A monopolist certainly would meet this condition, while perfectly competitive firms cannot. 2. Different Consumer Groups: Consumers must differ in their willingness to pay for the product and the firm must be able to identify these different groups of customers. It’s quite easy for movie theaters to distinguish senior citizens by asking them to provide an ID as verification of age. 3. Resale is not possible: It must be impractical for one consumer to resell the product to another customer. Airlines have strict rules which prevent one person from buying the ticket and then reselling that ticket to another individual. Figure 8 shows an example of price discrimination for a monopolist. The top panel of Figure 8 shows a monopolist who charges a single price of $4 per unit for its product. Customer B who was willing to pay $5.50 would have enjoyed a consumer surplus of $5.50-$4.00=$1.50. Likewise Customer A would have a surplus of $1.75. The area shaded in blue indicates the consumer surplus that would exist if the monopolist charged $4 per unit. The bottom panel of Figure 8 shows a monopolist who knows exactly the willingness to pay for each consumer of their product and has the ability to charge them different prices. This situation is called perfect price discrimination. As an example, the monopolist would know that Customer A would be willing to pay $5.75 for the product and would charge them that amount. In such a case, there will be no consumer surplus as it all will be captured by the monopolist. It’s important to note that a firm that can perfectly price discriminate will see that MR=P. Unlike our initial assumption, the firm doesn’t have to lower the price on all goods sold previously in order to sell an extra unit. Thus the demand curve and MR curve will be the same. Also note that the equilibrium condition where MR=MC occurs at the perfectly competitive outcome. Thus when a monopolist can perfectly price discriminate, there will be no deadweight loss and the firm will produce at an efficient level. On the other hand, there will be no consumer surplus and the firm will reap all the benefits. IV. Anti-Trust Policies We’ll take a brief look at two major pieces of legislation in the United States that was aimed directly at monopolies. A. Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 The Sherman Act of 1890 was the first legislation that was aimed at monopoly power. It made it illegal to monopolize a market or to engage in practices that result in a restraint of trade. The language of the legislation was very broad and it left it to the courts to try to interpret the law. In 1911, in a major case by the Supreme Court, the Standard Oil Company was broken up using the statutes of the Sherman Act. Standard Oil controlled 90% of the market of refined petroleum products, and the Supreme Court found that the owner John D. Rockefeller had used “unnatural methods to maintain his monopoly power and drive his rivals out of business. He coerced railroads to give him special rates for shipping and he spied on his competitors. The government broke up Standard Oil into 34 separate companies. The American Tobacco Company was also broken up in that year for also engaging in unfair trade practices. American Tobacco would drive rivals out of business by agreeing to exclusive contracts with wholesalers that prevented them from purchasing cigarettes from other companies. The Supreme Court did however in its rulings made clear that being big was not necessarily bad. Violation of the Sherman Act would be based on whether a firm engaged in unreasonable tactics to maintain their status. B. The Clayton Act of 1914 Many of the ambiguities surrounding the Sherman Act was resolved by the Clayton Act of 1914. The Clayton Act outlawed specific practices that discouraged competition such as tying contracts (forcing a customer to buy one product to obtain another), mergers that would substantially reduce competition, and price discrimination that would significantly reduce competition. Congress also created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate companies to ensure compliance with the existing anti-trust laws.