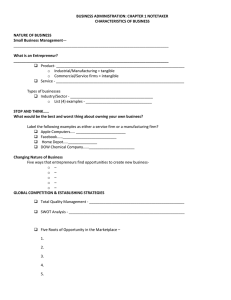

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background

advertisement