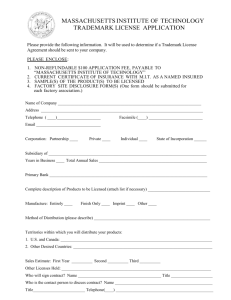

MAKING A MARK IN THE INTERNET ECONOMY: A ADVERTISING

advertisement