1 Benedict E. DeDomincis, “Globalization versus Americanization: The Case of the

advertisement

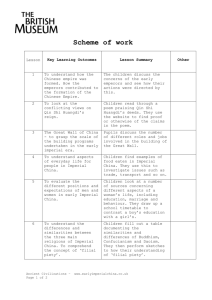

1 Benedict E. DeDomincis, “Globalization versus Americanization: The Case of the American University in Bulgaria”1 Types of Imperial Control.2 Covert Overt Direct Indirect Imperialism Colonialism Formal Nonformal Imperialism Colonialism Covert Overt Direct Indirect The method by which the external imperial power attempts to control another community will affect drastically its subsequent political development. One idealtypical form of colonial rule is direct, formal rule. The imperial power appoints a governor or high commissioner with troops from the metropole. This form of imperial control is probably the least detrimental to a community’s subsequent political development. This kind of colonial experience unifies the native political elite of different ethnies in the community in the course of resistance to this imperial control. Indirect, formal rule is another kind of imperial control. Local, traditional ruling elites rule in the area with the "advice" of the imperial power in the form of the formal presence of advisors, as well as security arrangements, etc. Pathological stereotypical legacies or indirect forms of imperial intervention are more likely to include majority identification of a collaborating minority as having a predisposition to treason. Not surprisingly, the minority will have a greater predisposition to fear the nationalism of the majority, making them more sympathetic to external intervention. 1 The views which this synopsis contains are the author’s and do not express the policy or position of any group or constituency at the American University in Bulgaria (AUBG). 2 From Richard W. Cottam: Foreign Policy Motivation: A General Theory and a Case Study (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1977), p. 28. 2 Indirect, informal control is maintained without the overt presence of imperial personnel, although the imperial power continues to exercise the dominant form of control over the local ruling aristocratic elite. It exists today, for example, among the Sheikhdoms of the Arabian peninsula, with the British and particularly the US playing the informal-indirect imperial role. Informal rule means that the imperial power does not admit that it rules the country; it has only an embassy and it works through the local bureaucracy. In the informal direct ideal-typical case, the people of the imperial power actually become the ruling class. Historical cases include the Normans conquering England and the Arabs conquering the Egyptians. In the contemporary world, these cases are rare. Neocolonialism is informal control. Following decolonization after the Second World War, the Western intelligentsia does not like to admit that this control. Today’s prevailing formal ideological principles of democratic self-determination do not permit it. In colonialism using formal means of control, the local actors do know who their enemies are. Yet, as noted, in direct forms of control, the colonial invader appoints a governor. In indirect, it rules through a puppet government. Bulgaria’s History of Imperial Control Direct Indirect Formal 1) Ancient Macedonians/Greeks 2) Romans 6) Ottomans (14th –19th cent.) 5) Byzantine Greeks 7) Russians (1878-88) Informal 3) Slavs (5th-6th century) 4) Proto-Bulgarians (7th century) 8) Soviets (1944-1989) The history of imperialism should be looked at in terms of the temperament and the forms of control. Partly through shaping images of self and other during this critical process of group political awakening, the legacies of these imperial experiences affect the process of national value formation and expression, which includes both the prevailing community basis for nationalism as well as the prevailing ideology which associates with it. Application of images to stereotypical prevailing view ideal types in international relations: View of Object of Challenge3 Resultant, "ideal Perceived Perceived Perceived Threat/ Opportunity from the Cultural Distance of the Capability Distance of the typical" Stereotype of the target target in relation to self target in relation to self target "Diabolical Enemy" Similar Similar Threat "Bully" Superior Similar Threat "Barbarian" Superior Inferior Threat "Colonial" Superior Superior Threat "Degenerate" Similar Similar Opportunity "Proxy Degenerate" Inferior Similar Opportunity "Imperial" Inferior Inferior Opportunity 3 Richard W. Cottam, The Return of Politics to International Strategy (unpublished manuscript), p. 184. 3 Political Images and Social-Identity Strategies4 Social-Identity Patterns of in-group behavior which result from holding In-group’s image held the group image of the policy target regarding a policy target out-group; creativity, competition when possible Enemy out-group; creativity, indirect competition Barbarian out-group; mobility, creativity, competition when relationship is unstable Imperial Out-group; maintain status quo Colonial Out-group; competition Degenerate Out-group; competition, destroy Rogue Ingroup; mobility, creativity Ally Transition Bulgaria and the American University in Bulgaria (AUBG) The prevailing view of AUBG is that it is a representative of the US’ political commitment to Bulgaria and to Southeast Europe. AUBG has received around $60 million of financial support from the United States Agency of International Development from 1991 to the present. Today, the US is a source of perceived opportunity to overcome poverty and any lingering threat of Russian revanchism. On the AUBG micro-organizational level, however, polarization over the academic market pay differential between Western and SE European regional faculty generates a perception of threat as well as opportunity. Regional faculty salaries at AUBG are typically three, four, or five times what these faculty members would receive at Bulgarian institutions. Also, affiliation with AUBG provides status outside of AUBG in the Bulgarian and regional context as well as providing access to additional external material resources, i.e. grants and fellowships, even western jobs. Still, their relevant comparison set appears to be the expatriate Western faculty. Bulgarian faculty concentrate in the physical, mathematical and computer science disciplines. Receiving their formal education during the Communist era, these faculty typically have a prestigious national reputation. Moreover, their skills are highly valued in today’s transition Bulgaria. Recent news reports highlight the IT sector as a focus of foreign direct investment.5 The justification for paying expatriate faculty a salary comparable to the US market is to attract and keep such faculty at AUBG. Of course, this pay differential will equal out over time as the Bulgarian economy grows at a rapid pace. In the mean time, a well-developed faculty evaluation system is essential in order to differentiate among the faculty individually, partly in order to avoid this difficult differentiation between “us” and “them,” i.e. “we Bulgarian faculty” versus “the Americans” (anybody coming from the Western market). The threat is not to economic interests, but rather, to individual national identity dignity interests. The inadvertent, implicit statement that the local faculty have second class status by earning a fraction of an American expatriate’s salary is an evident if unintended one. 4 Martha L. and Richard W. Cottam, Nationalism and Politics: The Political Behavior of Nation States (2001, Lynne Reinner Publishers), p. 100. 5 Kerin Hope, Raphael Minder and Theodor Troev, “Crime a black mark for thriving Bulgaria,” Financial Times, 26 April 2005, at www.ft.com on 7 May 2005. This article notes the importance of Soviet-era generated expertise in IT in Bulgaria in attracting much of today’s foreign direct investment there; the old Communist Europe regional economic orchestration regime, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, designated Bulgaria as the center of the block’s computer industry. 4 Meanwhile “Writing Across the Curriculum” (WAC) no longer receives support from all AUBG academic disciplines, partly because native fluency in English is viewed as an illegitimate justification for this national market pay differential. To help overcome these stereotyping tendencies, the AUBG faculty evaluation procedure needs to provide opportunities for social creativity in comparison. Its development began in earnest in 1997 with the adoption of a Total Quality Management approach at the time within the entire AUBG institution. The crisis which generated the institutional push to overhaul the evaluation procedure was a radical disjuncture between the student course evaluations and actual faculty member performance in the classroom and overall. The focus was on “continuous improvement” through the requirement of an annual goal-setting letter. From a positive perspective, it allowed the individual faculty member to have her or his own opportunities to explain what she or he was doing and to justify it convincingly. Feedback from the Provost ensured that the Faculty Evaluation Team would ideally highlight the unique contributions of an individual faculty member to the Mission of the institution, focusing specifically on teaching. The result ideally would be greater creative dynamism throughout the institution. Of course, Total Quality Management approaches require that the commitment to this approach be institution-wide. It also requires good faith on the part of all parties participating. In the worst case scenario, goal-setting letters can become means by which to penalize; failures at creative initiatives can become a source of political weakness. Faculty members who viewed the Administration as targeting them viewed the feedback from the Administration as a means by which to que the Faculty Evaluation Team (FET) to respond negatively towards a particular faculty member. The Admininstration could choose to put in a faculty member’s evaluation dossier any item it wished, including the goal-setting letters and feedback, should the faculty member under evaluation himself choose not to include this material. Among the problems: a number of regional faculty refused to submit a goal-setting letter. The reasons include discomfort with their proficiency in English. Conflict with the administration over the expectation to be at AUBG at least 4 full working days per week also has been an ongoing issue. Some of the American expatriate faculty felt that the administration was using the goal setting letter to bias the Faculty Evaluation Team against the faculty member undergoing evaluation. It also required a significant amount of time and effort from the Chief Academic Officer of the institution to review and comment on the goal-setting letters. In the course of institutional administrative change at AUBG, AUBG has evidently decided not to continue with the TQM approach. At the behest of interim administrators, AUBG chose not to continue with the goal-setting letter requirement in terms of formative evaluation. The Faculty Assembly chose to remove the goalsetting letter requirement in November 2003, and the AUBG Board of Trustees agreed to remove it from the AUBG Faculty Handbook in May 2004. The justification for doing so was evidently that it instigated greater conflict between faculty and administration. The administration would consequently make its personnel decisions on its own terms while the role of the FET would decline. One of the consequences of this decision is that Faculty oversight of faculty development has deteriorated. The Faculty Evaluation Team has less information with which to make its judgments. Given that evaluation now occurs once every three or five years for permanent faculty, critical institutional feedback for development in terms of faculty development has declined. Partly as a consequence, the latent nationalist resentments between American and Bulgarian faculty have become more intense. Administrative 5 consideration of faculty along national lines has become more pronounced as in-group formation has strengthened among the Bulgarian faculty. As a consequence, the latent tension between expatriate and local regional faculty has become more intense. In sum, for the TQM approach with formative and summative evaluation to succeed, goodwill must characterize the relationship among the different units of the institution. The ongoing administrative turmoil at AUBG has made generating such an institutional atmosphere difficult.