Who Blinks First? Legislative Patience and Bargaining with Governors THAD KOUSSER

advertisement

Who Blinks First

55

THAD KOUSSER

University of California, San Diego

JUSTIN H. PHILLIPS

Columbia University

Who Blinks First?

Legislative Patience and

Bargaining with Governors

When legislators and governors clash over the size of American state government, what strategic factors determine who wins? Efforts to address this question

have traditionally relied upon setter models borrowed from the congressional literature

and have predicted legislative dominance. We offer an alternative simplification of

state budget negotiations that follows the “staring match” logic captured by dividethe-dollar games. Our model predicts that governors will often be powerful but that

professional legislatures can stand up to the executives when long legislative sessions

give them the patience to endure a protracted battle over the size of the budget. In

this article, we present our analysis of an original dataset comprising gubernatorial

budget proposals and legislative enactments in the states from 1989 through 2004.

The results indicate strong empirical support for our predictions.

Who is more influential—legislators or governors—when they

bargain over the size of American state budgets? What institutional

features and strategic contexts help to determine each group’s level of

success? In any system of separated powers, understanding the

bargaining process between the legislative and executive branches is

crucial to predicting policy outcomes and uncovering the determinants

of political power. In this article, we explore legislative-executive

conflict across the American states using a bargaining model that differs

from the models utilized in much of the existing literature. A new data

source on gubernatorial budget proposals and legislative enactments

provides the testing ground for our model’s empirical implications.

Efforts to assess the budgetary influence of legislators and chief

executives have traditionally relied upon setter or spatial models of

policymaking. In these models, the outcome of interbranch bargaining

is a function of the various players’ preferences, the order of interactions, and the location of status quo policy (Romer and Rosenthal 1978).

LEGISLATIVE STUDIES QUARTERLY, XXXIV, 1, February 2009

55

56

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

Typically, the legislature is treated as a monopoly proposer, submitting

“take it or leave it” offers to an executive who possesses an absolute

veto. The executive is then forced to choose between the appropriations

figures contained in the bill and the reversionary or status quo point.

This reversion is almost always assumed to be the previous year’s

spending plan maintained, in the absence of legislative-executive agreement on a new budget, through a continuing resolution.

In spatial models, the legislature’s proposal power, combined with

its ability to credibly threaten to keep expenditures at the status quo

level, gives the legislature substantially greater influence over

budgetary outcomes than the executive holds. For instance, using a

spatial model of presidential-congressional bargaining, Kiewiet and

McCubbins (1988) have shown that when the president prefers smaller

expenditures than Congress proposes—the circumstance most favorable to the president—the president exerts only a limited influence

over budgetary outcomes. When the president prefers a higher level of

expenditures, the president has no influence at all. Kiewiet and

McCubbins’s insights have received additional support from a subsequent investigation by McCarty and Poole (1995).

In the study of American states, applications of setter models

also predict legislative dominance. In their influential analyses of state

budgeting under divided government, Alt and Lowry (1994, 2000)

amended the spatial model developed by Kiewiet and McCubbins to

account for the balanced-budget requirements that exist in most states.

In Alt and Lowry’s model, the legislature and governor must reach

agreement on fiscal balance (whether there is a surplus, deficit, or

balanced budget) in addition to fiscal scale. Alt and Lowry also added

an assumption, backed by Lowry, Alt, and Ferree’s (1998) empirical

work, that fiscal imbalance results in significant electoral losses for

the governor’s copartisans in the legislature.

Alt and Lowry’s model, like the Kiewiet and McCubbins model,

suggests executive weakness. When there is interbranch disagreement

over the size of the budget, the legislature can use its monopoly proposal

power to threaten the governor with fiscal imbalance by passing a

continuing resolution rather than a new budget. Since, in this model,

deficits or surpluses put the governor’s copartisans in the legislature

at risk, the governor will be forced to make significant concessions to

the legislature on fiscal scale in return for a balanced budget. After

reviewing the empirical predictions of their model under different fiscal

contexts and configurations of party control, Alt and Lowry concluded

that state legislatures are even stronger than Kiewiet and McCubbins

(1988) predicted Congress to be. Although governors can achieve some

Who Blinks First

57

of their fiscal goals when members of their party control one or both

houses of the state legislature, chief executives must make severe concessions when they bargain with a legislature fully controlled by the

opposition party. When each party controls one branch, according to

Alt and Lowry (2000, 1043), “In no case does the governor achieve a

significant shift in the budget target in the direction of her ideal point.”

While spatial models and their progeny have unquestionably

provided important insights into legislative-executive bargaining, we

believe that these models are not the most appropriate simplification

of budgeting negotiations in most American states. Their portrayal of

gubernatorial weakness contradicts much of the existing scholarship

in the state politics literature. Case studies (Bernick and Wiggins 1991;

Gross 1991), surveys of political insiders (Abney and Lauth 1987;

Carey et al. 2003; Francis 1989), and other qualitative works (Beyle

2004; Rosenthal 1990, 1998, 2004) all point to the extraordinary power

of governors; many even refer to the governor as the “chief legislator.”

According to these analyses, governors can, and often do, dominate

the legislature with respect to the eternal question of how much to tax

and spend.

Additionally, the conclusion that the legislature can force the

governor to accept an unfavorable deal largely depends on the assumption that the reversion point in the absence of a budget agreement is

the status quo preserved through a continuing resolution. Continuing

resolutions, although frequent in federal budgeting (Fenno 1966;

Meyers 1997; Patashnik 1999), are not common or important considerations in state budget negotiations. Only nine states permit some

form of continuing resolution (Grooters and Eckl 1998), and even these

measures are labeled “minibudgets” (Connecticut), “interim budgets”

(New York), or “stopgap funding” (Pennsylvania). None can become

permanent, and the players in budget negotiations do not hope or fear

that they will avoid crafting a new budget.

We would argue that a late budget, with all of the political and

private costs that it entails, is the relevant reversion that drives

interbranch negotiations. In most states, a delayed budget triggers an

automatic shutdown of the government (Grooters and Eckl 1998). In

all states, it generates unfavorable press and usually a special legislative

session. Public polls conducted in California,1 New York,2 and New

Mexico3 have all demonstrated that a late budget cuts deeply into the

approval ratings of both branches. The possibility of voter disapproval

evens the field on which the budget bargaining game is played. Neither

branch likes a delayed budget agreement or a government shutdown,

so both sides face incentives to deal. The legislature’s proposal power

58

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

erodes when legislators cannot fall back on an acceptable status quo.

This legislative limitation should make governors more powerful in

the budgetary process than spatial models predict, a dynamic suggesting

that an alternative model should be sought for describing state budget

making.

In this article, we offer an alternative simplification and discuss

our tests of its main implications. Our theory is based on formal models

devised by Rubinstein (1982, 1985) and Osborne and Rubinstein (1990)

and applied to state budget bargaining by Kousser (2005). Our model

treats the outcome of interbranch bargaining as a function of the institutional capacities and constraints of the legislature. We view budget

bargaining as a “staring match” in which the political and personal

costs of a delayed budget swamp the influences of proposal power and

status quo policies. Because the governor and legislature face shared

costs of delay, they both have incentive to reach an agreement quickly.

Negotiations are carried out informally, behind closed doors, rather

than in a sequence of bills sent to the governor’s desk. In the staringmatch dynamic that this negotiation creates, the identity of the “winner”

depends on relative levels of patience or endurance. Governors can

prevail in this game if they are willing to endure longer budget negotiations than their legislative opponents can stand.

In our application of the divide-the-dollar game, governors are

patient bargainers, but legislative patience is treated as a function of

professionalization. The governorship, in all states, is a full-time and

well-paid job; governors can afford to engage in long and protracted

negotiations over the budget. State legislatures, on the other hand, vary

widely in session lengths. Legislators receive sizable salaries to meet

nearly year-round in states such as California, New York, Illinois, Ohio,

and Massachusetts, but they meet as briefly as two or three months a

year in New Mexico, Georgia, Utah, and Kentucky and earn only small

salaries or per diems. Legislators in these less-professionalized

chambers usually hold second jobs to which they must return soon

after the legislative session. These individuals pay high opportunity

costs if their governor vetoes their budget and calls them in to a special

session. These costs make “citizen” legislators less patient, relative to

the governor and their counterparts in more-professionalized legislatures, and give the governor a bargaining advantage. Our staring-match

model predicts that the governor will be more successful when

bargaining with citizen, as opposed to highly professionalized, legislatures. And, since relatively few state legislatures are highly

professionalized, governors should generally be quite powerful in the

budgetary arena.

Who Blinks First

59

Clearly we are not the first to argue that full-time legislatures

exert greater influence over budgetary matters than their part-time

counterparts, but our treatment of professionalization differs significantly from the models in much of the existing literature. Traditionally, professionalized legislatures—houses with longer sessions, higher

salaries, and plentiful staff support (King 2000; Squire 1992)—are

considered more powerful because they possess an increased intelligence capacity (Rosenthal 1990). These legislatures usually have a

large staff dedicated exclusively to fiscal policy, a revenue-estimating

capability independent of the executive branch, and a sizeable

contingent of experienced legislators. These features are believed to

reduce the governor’s traditional informational advantages and enhance

legislative independence and assertiveness (National Conference of

State Legislatures 2005). While professionalization may indeed have

these effects, we argue that its real advantage is that long sessions

make legislators willing to endure extended interbranch negotiations

over the size of the budget.

To test the predictions generated by our abstraction of the

budgeting process, we estimated an econometric model of the outcomes of interbranch bargaining over the size of the state budget. We

used an original dataset of annual gubernatorial budget proposals and

the corresponding legislative enactments culled from various issues

of the National Association of State Budget Officers’ Fiscal Survey of

States. We examined data for all states over a 16-year period, fiscal

years 1989 through 2004.

Our analysis revealed striking evidence of gubernatorial strength

in budgetary negotiations. Across all types of states and legislatures,

our econometric estimations show that the chief executive’s proposed

budget has a positive and statistically significant effect on the budget

that is ultimately passed and signed into law. Most important, we found

gubernatorial influence to indeed be inversely related to legislative

professionalization. Among states with citizen houses, there is nearly

a one-to-one relationship between the size of the gubernatorial proposal

and the size of the enacted budget. In states with professional legislative

bodies, the magnitude of gubernatorial influence falls by approximately

half. These results are consistent with the expectations of our staringmatch model and provide systematic empirical evidence that this

simplification of budget bargaining may be more appropriate for the

state context than the more traditionally utilized setter or spatial models.

In the next section, we present our staring-match model of state

budget bargaining in greater detail. We discuss the logic of the game,

its assumptions, and its predictions. Next, we present our estimation

60

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

of an econometric model of the outcomes of legislative-executive

bargaining and interpret the results. We break down the components

of professionalism to show that professional legislatures are generally

more powerful than citizen houses, and it is longer sessions, rather

than higher salaries or more staff support, that grants them this power.

We then consider the potential endogeneity of gubernatorial budget

requests. We conclude by exploring the implications of our analysis

for the study of state politics.

Legislative and Gubernatorial Influence on State Budgeting

A Staring-Match Model of the Appropriations Process

To analyze the outcomes of legislative-executive bargaining over

the size of the budget, we applied the framework of the divide-thedollar games developed by Rubinstein (1982, 1985) and Osborne and

Rubinstein (1990). Our application of their games treats bargaining

between a governor and state legislature as a staring match; “blinking”

means signing or passing a proposal that closely reflects the demands

of one’s opponent. Hereafter, we refer to this treatment as “the staringmatch model.” The winner is determined largely by the relative patience

levels of the players, which, we argue, are functions of their institutional characteristics.

The game we describe here, like its spatial counterparts, is highly

stylized and abstract, lacking the detailed discussion of the appropriations process contained in many descriptive analyses of state budgeting

(cf. Garand and Baudoin 2004, National Association of State Budget

Officers 2002, and Rosenthal 2004). Yet this abstraction is useful for

conveying the logic of our argument in a simple, direct manner.

Furthermore, like the game’s basic intuition, many of the assumptions

made in the game conform nicely to budget bargaining at the state

level and are consistent with observations made by qualitative studies

and in interviews with legislative staff. A more-detailed discussion of

the assumptions necessary to apply the staring-match model to state

budget negotiations, along with proofs of the propositions we present,

can be found in Kousser’s work (2005, ch. 6).

Since this model has been used less frequently than spatial models,

we will review its assumptions and notation. There are two players, a

governor (PG) and a legislature (PL), each behaving as if it were a

unitary actor. Although this assumption ignores important intrabranch

divisions, each branch has rules for aggregating internal preferences

into a final position, justifying the common use of this assumption in

Who Blinks First

61

models of interbranch bargaining (Alt and Lowry 2000; Cameron 2000;

Kiewiet and McCubbins 1988). When both the legislature and the

governor’s office are controlled by one political party, their disagreements may be fewer than under divided government. But because there

is still likely to be interbranch conflict, whether government is unified

or divided,4 we assumed that the branches must agree on how to “divide

the dollar” of the budget. The branch winning the biggest share of the

dollar (in the game) exerts the most control over the size of the state

budget (in our application of the game). The division of the dollar is

represented as an offer of (XL, XG), and XL can fall anywhere in the

interval [0, 1]. Rounds of play are numbered as T = {0, 1, 2, . . .}.

In the most natural application, the game begins with the legislature proposing how to divide the budget’s figurative dollar. (The

governor could also begin these informal negotiations and, as we later

demonstrate, the logic of the game would be the same and the division

of the dollar would remain largely unchanged.) Faced with this offer

of a budget with a given size, the governor either accepts and signs it

or sends the game into its next stage. The governor begins the second

stage with a counteroffer,5 but even if the legislature immediately

accepts it, the agreement has been delayed one round and both sides

receive a payoff that is discounted according to their patience levels.

The discount factor is conventionally denoted by δ.

Rounds of alternating offers continue until one player accepts

the other’s proposal. For every round that a bargain is delayed, the

utility a player receives from her or his portion of the dollar is equal to

that portion multiplied by δ. Assuming that this discount factor remains

constant from round to round, we would designate the value of an

agreement in round t to PL at the beginning of the game as XLδt. When

a player’s patience is set at δ = 0.9, the player will be indifferent between

receiving 45 cents in one round and getting 50 cents in the next, because

50 cents deflated by 0.9 gives the player 45 cents of utility.

We employed this deflation because continuing resolutions are

rare in states and a delayed budget deal is costly to both branches.6

When the players fail to adopt a state budget on time, the governor and

legislature’s public images are harmed. Even when the delay does not

run afoul of constitutional requirements, the failure to pass a new budget

is politically infeasible, because it denies the legislature and governor

the chance to create new programs and alter the composition of

spending. In either case, the status quo is a nonstarter, and the reversion point that dictates the players’ incentives is a delayed budget.

Each player is thus willing to give up some of the dollar to reach an

agreement early. Failure to reach any agreement is, of course, the worst

62

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

possible outcome for both players, giving each zero utility. These

features characterize Rubinstein’s basic bargaining game.

Proposition 1. In a game satisfying all of these assumptions and where

both players face the same discount factor δ, there exists

a unique subgame perfect equilibrium.7 PL will always

propose the division (XL*, XG*) and accept an offer only

if it is better than or equal to YL*. Whenever it is PG’s

turn to make an offer, PG will propose (YL*, YG*) and

always accept an offer that matches or beats XG*. In

equilibrium, PL proposes (XL*, XG*) in round t = 0, and

PG accepts.

1

δ

( X L* , X G* ) = (

,

)

1+ δ 1+ δ

δ

1

(YL* , YG* ) = (

,

)

1+ δ 1+ δ

The proof of this proposition is outlined by Osborne and

Rubinstein (1990, 45) and traced out for the state politics application

by Kousser (2005, 233–37). Proposition 1’s implication for state politics

is that governors will not face a severe bargaining disadvantage because

they lack formal proposal power. In contrast with setter models, in

which gubernatorial power depends on a governor’s spatial preferences relative to the legislature’s and the level of fiscal imbalance in a

state,8 in our version of Rubinstein’s model, governors can receive

some of what they want no matter which direction they wish to move

the size of government and no matter who begins the bargaining.

Regardless of which branch makes the first offer, power over the budget

will be divided quite equitably. Both branches bargain in the shadow

of a late budget and the political penalties it can bring. Both are eager

to avoid delay, and whichever branch can move first makes a fair offer

that it knows the other branch can afford to accept. In the most straightforward application of the staring-match model, this offer comes when

the legislature passes a budget bill. But even if the governor’s public

budget proposal, which often receives much media attention and sets

the agenda for later negotiations, is thought of as the first offer, the

theoretical prediction for the division of the dollar does not change

radically. As the payoffs demonstrate, the “first mover” advantage that

accrues to the branch making the initial offer is small when both players

are relatively patient, and not tremendously large even when they are

in a hurry to pass a budget. When both players discount payoffs that

are delayed one round by a factor of 0.9, the first mover receives 52.6

Who Blinks First

63

cents of the dollar and the other branch gets 47.4 cents. Even when the

discount factor equals 0.7, the division of the dollar is still a somewhatequitable 58.8 cents to 41.2 cents. Regardless of which branch is

thought of as making the first offer, Proposition 1 leads to the following

empirical implication:

Hypothesis 1: Governors will exert a powerful influence over the size

of state budgets.

Varying Legislative Patience

The basic model assumes that governors and legislators possess

the same patience level, but this assumption may not always hold true.

In particular, the members of a citizen legislature should be significantly less willing to engage in protracted budgetary disputes with the

governor than their more-professionalized counterparts. The rationale

here is that, in addition to political costs that both branches pay when

there is budgetary gridlock, lawmakers serving in a lessprofessionalized legislature face private costs of delay. These costs

will decrease the legislature’s patience and advantage the governor.

There are, of course, several relatively professionalized state

legislatures. These chambers resemble the U.S. House of Representatives: they meet in lengthy sessions, their members are well paid, and

the legislature employs numerous nonelected staff. In states such as

California, New York, and Michigan, there are few, if any, restrictions

on the number of days the legislature may meet; as a result, lawmakers

are in session much of the year. Furthermore, legislators serving in

these chambers receive annual salaries in excess of $75,000, as well

as generous per diems (Council of State Governments 2005). These

lawmakers can therefore treat legislative service as a career and do not

need second jobs, even as the session length makes holding a second

job close to impossible.

Most state legislatures, however, are notably less professionalized.

In these chambers, the number of days that legislators are allowed to meet

is often constitutionally restricted. On average, regular sessions are limited

to approximately 90 calendar days per year; in extreme cases, sessions are

constrained to no more than 60 or 90 days biennially. Compensation for

service in most chambers is also low or nonexistent. To support themselves and their families, legislators in citizen chambers usually hold

second jobs to which they must return soon after the legislative session.

As a result, members of a part-time body face high opportunity

costs when they fail to reach agreement on a budget with the governor.

64

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

In the absence of such an agreement, legislators are usually forced

into what may be a time-consuming special session and are prevented

from pursuing their private careers or personal lives. The prospect of

leaving their day jobs to resolve budget conflict should make members

impatient. On the other hand, governors pay much lower private costs

when they veto a bill at the end of a session. They may force a special

session, stalling whatever private, travel, or governing plans they might

have,9 but because all governors are paid well to do their job fulltime,10 they can endure round after round of negotiations. Participants

in gubernatorial negotiations with the less-professional legislatures

point out the paramount importance of this dynamic. A senior advisor

to Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber explained that, “As session goes

on, the wait is in our favor.”11 In New Mexico, a special session called

by Governor Gary Johnson to resolve the 2000 budget standoff led

legislators to grouse, take political heat, and ultimately accede to many

of the governor’s demands.12 We therefore expected professional

chambers to be able to match the governor’s endurance, whereas parttime bodies would be vulnerable to threats of a veto and extended

negotiations. One piece of descriptive evidence consistent with our

expectation is that budget standoffs, although rare, occur primarily in

professional, full-time legislatures.13

This potential asymmetry in the patience levels that the branches

possess can be formalized in an extension of the basic Rubinstein model

in which the two players have different discount rates. When a citizen

legislature negotiates, δL will be lower than δG. If the governor’s

advantage in patience is large, then it will swamp the advantage that

the legislature holds from moving first. Proposition 2 is simply a lessgeneral form of Proposition 1 in which discount rates are allowed to vary.

Proposition 2. In a game similar to the basic game but where players

face individual discount factors δL and δG, there exists

a unique subgame perfect equilibrium. PL will always

propose the division (XL*, XG*) and accept an offer only

if it is better than or equal to YL*. Whenever it is PG’s

turn to make an offer, PG will propose (YL*, YG*) and

always accept an offer that matches or beats XG*. In

equilibrium, PL proposes (XL*, XG*) in round t = 0, and

PG accepts.

1 − δ G δ G (1 − δ L )

( X L* , X G* ) = (

,

)

1 − δ Gδ L 1 − δ G δ L

(YL* , YG* ) = (

δ L (1 − δ G ) 1 − δ L

,

)

1 − δ Gδ L 1 − δ G δ L

Who Blinks First

65

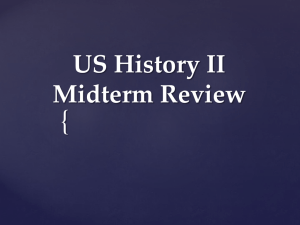

FIGURE 1

Payoffs for Legislatures with Different Levels of Patience

0.6

Le gis la ture makes

M a ke s initial

Initia l P

ro po s a l

Legislature

proposal

0.4

0.3

0.2

Legislature’s Share of the Dollar

0.5

Go ve rno rmakes

M a ke sinitial

Initia lproposal

P ro po s a l

Governor

0.1

0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

Legislature’s Patience Level

The exact payoffs that the legislature receives at different levels

of legislative patience are displayed graphically in Figure 1. One can

see how steeply the legislature’s share of the dollar drops as its members

become less and less patient, assuming that the governor has a discount

rate of δ = 0.9. Although we do not investigate variations in the

governor’s patience level here, it likely changes with such factors as

approval ratings, the timing of the next election, and the governor’s

political ambitions. Investigations of these variables may provide

fruitful further tests of the implications of the model.

The solid line maps the payoffs when the legislature begins the

bargaining, and the dotted line shows the results if the governor moves

first. The gap between these lines—the first-mover advantage—is

relatively narrow. What really determines who will control the budget

is the legislature’s patience. A professional legislature that can credibly

threaten to wait the governor out in a special session will win, gaining

52.5 cents if it is equally as patient as the governor. If the private

demands on members of a citizen legislature reduce their discount

rate to 0.5, then they will get a mere 18.2 cents, even when they move

first. Hypothesis 2 states the specific, testable implication of this

theoretical finding.

66

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

Hypothesis 2: The influence that governors exert over the size of their

state budgets will grow as the level of legislative

professionalism in their states declines.

Before discussing the tests our hypotheses, it is worth noting

that the centrality of patience or discount rates in our model is one of

the features that most clearly distinguishes it from existing analyses.

Spatial approaches to legislative-executive bargaining, at both the

national and state levels, rarely consider the potential effects that shifts

in discount rates may have on outcomes (Alt and Lowry 1994, 2000;

Kiewiet and McCubbins 1988; McCarty and Poole 1995; but see Banks

and Duggan 2006). Even when the patience levels of the players are

allowed to vary, spatial models predict no effect. Primo (2002), for

instance, examined how some of these dynamics might affect Romer

and Rosenthal’s (1978) model. He found that, even when spatial models

are extended to multiple stages of bargaining, discount rates do not

factor into the equilibrium. Primo’s results suggest that impatient citizen

legislatures should not face a bargaining disadvantage because

“impatience and time preferences may not be key features of political

bargaining” (421).

Testing Predictions of the Staring-Match Model

We tested our hypotheses by systematically examining the

relationship between the size of the governor’s proposed increase in

total per capita state expenditures (measured as a percentage of the

previous year’s budget) and the size of enacted spending change—

that is, the change contained in the budget ultimately adopted by the

legislature and signed into law (again measured as a percentage of the

prior year’s budget).14 Unlike most of the existing literature, our study

gauges gubernatorial power by directly measuring the policy preferences of governors, rather than assuming that their party affiliations

tell us exactly what they want.

Prior studies of variation in state policy outputs that relied

exclusively on measures of party control as a proxy for gubernatorial

and legislative preferences gained their causal traction from the

assumption that Democrats always and everywhere want government

to expand, or that the magnitude of policy disagreements between the

two major parties is constant across states (Alt and Lowry 2000; Dye

1966, 1984; Garand 1988; Hofferbert 1966; Kousser 2002; Smith 1997;

Winters 1976; but see McAtee, Yackee, and Lowery 2003 for a relaxation of the latter assumption). None of these studies has found that

Who Blinks First

67

governors can move policy in their preferred direction in a statistically significant manner.

Instead of using party affiliations as a proxy, we chose to measure

executive preferences directly, by recording the percentage change in

per capita expenditures that the governor proposes at the beginning of

the year. Our choice is similar to Clark’s (1998) strategy of gathering

gubernatorial recommendations for agency budgets from 20 states and

Canes-Wrone’s (2001) use of presidential budget proposals to analyze

federal bargaining. A dataset that systematically gathered legislative

budget proposals would be ideal, but no such dataset exists. Still, using

gubernatorial proposals for spending changes as an independent

variable and legislative enactments as our dependent variable, we can

see how far different types of legislatures shift policy from what the

governor wants. This is the same empirical strategy that Kiewiet and

McCubbins (1988) employed in their influential study of presidentialcongressional bargaining.

As mentioned previously, we collected our dataset of gubernatorial budget proposals and enacted state budgets from various issues of

The Fiscal Survey of States, a publication of the National Association

of State Budget Officers (NASBO). Each year, NASBO conducts two

surveys of state budget officials to identify trends and changes in state

fiscal policy. The spring survey gathers information concerning the

governor’s proposed general-fund budget, and the autumn survey identifies details of the enacted budget (usually Table A-3 in both reports).

Our analysis includes data for all states over a 16-year period, fiscal

years 1989 through 2004. Data prior to fiscal year 1988 are unavailable. Since NASBO consistently reports data in current dollars, we

converted the values for each year into 2000 dollars using the Consumer

Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U).

Evaluating the predictive power of the staring-match model also

required us to identify an appropriate measure of the professionalization

of state legislatures. A venerable literature in state politics has demonstrated the importance of variation in legislative salaries, session

lengths, staff support, and other resources (Berry, Berkman, and

Schneiderman 2000; Fiorina 1994; Hamm and Moncrief 2004; Karnig

and Sigelman 1975; Roeder 1979; Squire and Hamm 2005; Thompson

1986). Many researchers follow Squire (1992, 72) or King (2000, 329),

combining the components of legislative professionalism into a single

index. To be consistent with the existing literature, we began with this

approach. We employed the widely used trichotomous categorization

developed by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL),

as well as Squire’s (1992) continuous index. Both measures are based

68

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

upon the length of time that legislators spend in session, the amount of

their total compensation, and the number of legislative staff members.

Because levels of state professionalism changed dramatically from the

1960s through the 1980s but were relatively stable during our period

of study, both of our measures are constant in each state across time.

We recast the NCSL’s red, white, and blue categories as “professional,”

“semiprofessional,” and “citizen.” As a report by the NCSL (2005)

details, lawmakers in professionalized bodies dedicate much more time

to legislative service, earn about four times as much, and work with

eight times as many staff members as their counterparts in citizen

legislatures.

We began our analysis by examining, for each type of legislature,

the bivariate relationship between the governor’s proposed budget and

the enacted budget in all states, with three exclusions. We excluded

Alaska and Wyoming because they both rely heavily upon severance

taxes on natural resources. The use of severance taxes results in fairly

dramatic year-to-year variation in tax revenues and thus expenditures.

These variations are driven largely by the global commodities market,

as opposed to the budgetary choices of legislators and governors

(Matsusaka 2004). We also excluded Nebraska because of its nonpartisan legislature.

Our preliminary results, reported in Table 1, are entirely consistent

with the hypotheses derived from the staring-match model. Across all

three categories of legislatures, the coefficient on the variable that

measures the size of the gubernatorial budget proposal is positive and

statistically significant at the 99% level. This result provides support

for our contention that governors are consistently powerful in the

budgetary arena (Hypothesis 1). As predicted in Hypothesis 2, the

magnitude of the effect is inversely related to legislative

professionalization. Among citizen bodies, this coefficient is 0.86.

Substantively, this finding indicates that when a governor negotiating

with a citizen legislature proposes increasing the budget by 1%, the

final enacted budget should increase by 0.86%. A proposed cut in

spending—although empirically much rarer—would bring an

analogous decrease in the size of the budget. When a governor

negotiates with a more-professional legislature, however, the governor’s

power to dictate fiscal outcomes declines. A proposed change of 1%

leads to an enacted increase of only 0.73% when the governor negotiates

with a semiprofessional legislature and a 0.46% change when the

governor faces a professional house. These differences, we will later

show, are statistically meaningful and still present when other factors

are held constant. Furthermore, among states with citizen legislatures,

Who Blinks First

69

TABLE 1

Governor’s Influence by Type of Legislature

Variables

Citizen

Semiprofessional

Legislatures

Legislatures

Governor’s Proposal

.86**

(.05)

.73**

(.08)

Professional

Legislatures

.46**

(.07)

All

Legislatures

.90**

(.07)

Squire’s Index of

Professionalism (1992)

__

__

__

.01

(1.68)

Governor’s Proposal × Squire’s

Index of Professionalism

__

__

__

–.83**

(0.20)

1.34**

(.29)

1.98**

(.44)

1.57**

(.56)

1.62**

(0.46)

Constant

N

R2

286

.48

370

.18

178

.19

852

.25

Note: Table entries are regression coefficients. In the “All Legislatures” model, the estimated

coefficient for a governor’s proposal represents the effect that this variable would have in a

hypothetical legislature with a “0” level of professionalism, measured on Squire’s scale.

**p < .01.

the governor’s budgetary proposal alone explains almost half of the

variation in outcomes, but among states with more-professionalized

legislative bodies, the governor’s proposal accounts for less than 20%

of the variation in outcomes.

The last column in Table 1 combines data from all three types of

legislatures with an interaction testing the hypothesis that a governor’s

proposal will have a smaller effect on the final budget outcome when

the legislature is more professional according to Squire’s (1992)

continuous measure. This interaction effect is strongly significant in

the expected direction. To interpret it, we obtained the effect of a

governor’s proposal when the legislature has a given level of professionalism; we added the product of that given level and the interaction

coefficient (–0.83) to the estimated coefficient of a governor’s proposal

alone (0.90). The results indicate that a governor’s proposed 1%

increase in the size of the budget should translate into a 0.88% increase

in spending when the governor negotiates with a legislature like Utah’s,

which is one standard deviation below the mean level of professionalism,

but only a 0.62% increase when the state’s legislative professionalism

registers one standard deviation above the mean, as in Pennsylvania.

70

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

Altogether, these results provide preliminary evidence that governors,

while powerful, are less influential in the face of legislatures that meet

in long sessions, pay high salaries, and provide staff support.

The results reported in Table 1 may of course reflect the influence

of omitted variables. We addressed this problem by conducting a

multiple regression analysis that included a number of potentially

influential political and economic variables. The first of these variables

is the partisan composition of the legislature. Existing research in state

politics has found evidence, albeit weak and oftentimes conditional,

that Democratic control of the legislature leads to a larger state public

sector and larger year-to-year increases in expenditures or revenues

(Alt and Lowry 1994, 2000; Phillips 2005). To allow for this possibility,

we employed a continuous measure of the legislative strength of the

Democratic Party in each state, calculated as the weighted percentage

of Democrats serving in both the state’s lower and upper legislative

chambers, recorded from appropriate editions of the Council of State

Governments’ Book of the States. Smith (1997) has identified this

approach as the most appropriate method for capturing the partisan

makeup of state government. Additionally, we accounted for crosssectional variations in the timing of state budget processes to ensure

that our measure accurately reflects the partisan composition of the

legislature at the time the budget was passed and signed into law.

Because empirical exploration indicated that the power of governors

was not contingent upon the presence of divided government,15 we did

not include any measures of divided government in the models

presented. Similarly, although the results of an unreported analysis

showed that governors who possess more institutional budget powers

according to Beyle’s (2004) index exert more influence over fiscal

changes, we omitted this test from our final models, because the effect

fell short of statistical significance and would have required threeway interactions. We also omitted from the final reported models

potential control factors such as whether a state had an annual or

biennial budget and whether or not it allowed continuing resolutions.

These factors (either entered alone or in interaction with a governor’s

proposal) did not have large or statistically significant effects, and

their exclusion did not substantially change the estimated effects of

our key variables of interest.

Previous research has also shown that economic factors are

important determinants of state budgetary policy (Dye 1966, 1984;

Winters 1976). We allowed for these influences by utilizing, as independent variables, per capita income (measured in thousands of dollars)

and the state-level unemployment rate (both taken from the U.S. Census

Who Blinks First

71

Bureau’s Statistical Abstract of the United States). To control for the

possibility that state expenditures increase during election years (that

is, the presence of a political business cycle), we included a dummy

variable for years in which lawmakers must run for reelection, as

reported in the Book of the States. Finally, following Phillips’s (2005)

work, we also included the previous year’s per capita expenditures, as

reported in NASBO records, to control for status quo fiscal policy and

a lagged measure of the state’s budget surplus or deficit (measured as

a share of the total budget).

All of our econometric estimations also utilize year and state

fixed effects. The year fixed effects control for common shocks that

affect all states in a given year, such as changes in the national or

global economy or changes in the national political environment. The

state fixed effects capture all relevant variables that are idiosyncratic

to individual states or that remain unchanged over the time period of

our analysis, such as culture, voter ideology, and political institutions.

Of particular relevance, fixed effects control for other features of the

bargaining environment that may enhance a governor’s ability to prevail

in battles over the size of the state budget, such as the item veto and

gubernatorial impoundment powers.

The first of our multiple regression results are reported in Table 2.

Model 1 is a baseline estimation that includes all states but does not

account for cross-sectional variation in legislative professionalization.

As in Table 1, the coefficient on the governor’s proposal is positive

and statistically significant, indicating that governors are powerful

actors in the budgetary arena even after one controls for a number of

potentially confounding influences. Model 2 is a direct test of our

second hypothesis. Here the governor’s budgetary proposal is interacted with two dummy variables: one for the existence of a semiprofessional legislature and the other for a citizen body. The reference

category in this regression is professional legislatures. We did not

include separate dummy variables for each legislative type in the

equation because we used fixed effects, which account for the

independent effect of professionalization.16

This new estimation provides the strongest evidence yet for the

staring-match model. Once again, the size of the governor’s proposed

budget has a significant and positive effect on the size of the budget

ultimately adopted by the legislature and signed into law. Most

important, the coefficients on the interaction terms are also positive

and significant at the 99% level: the effect of the gubernatorial proposal

on the final budget increases in a statistically meaningful fashion as

the professionalization of the legislature declines. When the governor

72

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

TABLE 2

Governor’s Influence by Type of Legislature,

Full Multiple Regression

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3a

(Squire 1992)

Model 3b

(Squire 2007)

.50**

(.05)

.29**

(.07)

.80**

(.08)

.92**

(.09)

Governor’s Proposal ×

Semiprofessional Legislature

__

.25*

(.10)

__

__

Governor’s Proposal ×

Citizen Legislature

__

.49**

(.11)

__

__

Governor’s Proposal × Squire’s

Index of Professionalism

__

__

–.96**

(.21)

–1.05**

(.23)

Squire’s Index of Professionalism

__

__

__

5.32

(8.20)

Variables

Governor’s Proposal

% Democrat Legislature

–.06

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

–.08

(.05)

Lagged Expenditures per Capita

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.00

(.00)

Legislative Election Year

1.38

(.77)

1.56*

(.76)

1.58*

(.76)

1.91**

(.83)

Unemployment Rate

–.48

(.36)

–.56

(.36)

–.58

(.36)

–.66

(.40)

Personal Income per Capita

1.01**

(.37)

1.02**

(.40)

1.01**

(.37)

.63*

(.38)

% Lagged Surplus

.07

(.06)

.03

(.06)

.03

(.06)

.03

(.07)

–5.96

(9.49)

–4.02

(9.39)

–3.15

(9.39)

–7.15

(10.31)

787

787

787

787

.30

.32

.32

.30

Constant

N

R

2

Note: Estimated using state and year fixed effects.

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Who Blinks First

73

negotiates with a professional legislature, an executive proposal for

an additional 1% increase in state spending per capita leads to only a

0.29% change in the legislature’s enacted budget, all else being equal.

When the legislature is semiprofessional, this marginal effect grows

to 0.54%. It rises to 0.78% when the governor negotiates with citizen

legislators.

Tests also show that the difference between the coefficients on

our two interaction terms is itself statistically significant at the 95%

level: not only does the governor get significantly more of what she or

he wants when the chamber shifts from professional (our baseline

category) to citizen or semiprofessional, but the governor also gets

significantly more of what she or he wants when the chamber shifts

from professional to semiprofessional. These findings are consistent

with the bivariate results shown in Table 1, as well as with the results

of Models 3a and 3b, which use Squire’s (1992) continuous measure

of legislative professionalism and Squire’s (2007) updated, dynamic

measure17 rather than the trichotomous categorization. Again the

statistically significant coefficient on the interaction between a

governor’s proposal and the level of professionalism suggests that chief

executives have less power when bargaining with full-time legislatures.

Thus far we have discussed a measure of legislative

professionalization that aggregates the various components of this

concept—session length, compensation, and staff—into a single indicator. While there are strong theoretical and empirical reasons for this

aggregation, the staring-match model makes a prediction about which

of these components matter. In particular, it suggests that session length

is the primary factor affecting the legislature’s patience and thus the

governor’s power. By contrast, our application of the staring-match

logic does not predict that increased staffing will affect the balance of

power between the branches because it affects a legislature’s informational capacity rather than its patience. High salaries, which can free

legislators from other obligations, might also affect patience, but

members of houses that regularly meet for full-time sessions should

exhibit the highest levels of patience. To examine this claim and to

further explore the relationship between legislative structure and

bargaining outcomes, we replaced our summary measures with the

separate components of professionalism. The first measure records a

legislature’s level of compensation, including both base salary and per

diem expenses. The second measures session length, in legislative days

per biennium, and the third reflects the ratio of staff per legislator.

Because staff, salary, and session length are not perfectly collinear,18

we estimated their separate effects.

74

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

The results reported in Table 3 explore the effects of each of

these components of legislative professionalism on gubernatorial

power. Models 4, 5, and 6 estimate the influence of each component

separately, and Model 7 tests their combined effects. Whether analyzed

separately or together, the story is the same: session length provides

the link between professionalism and executive power, with the

governor exerting less control over the budget when a house meets for

longer and longer sessions. The interaction between total session days

and a governor’s proposal is statistically significant in the expected

direction, but changes in the other two components do not significantly alter the effect of executive proposals. To gauge the scale of the

effect of session length, we calculated the effect, according to the results

in our fully specified Model 7, of shifting this variable from one

standard deviation below its mean to one deviation above its mean.

Consider two legislatures, both of which pay the average salary in our

sample (about $25,000 a year), provide average staffing levels (3.5

assistants per legislator), and exhibit similar values on all of the control

variables. If one of these legislatures meets for 66 days over a twoyear period (a typical session for North Dakota’s legislature), then

every extra percentage-point increase in spending proposed by the

governor translates into a 0.78% increase in the enacted budget. If a

house is similar in all other respects but meets for 263 days per

biennium, as Wisconsin did for 1997 and 1998, then a change of 1% in

the governor’s proposal yields only an estimated 0.59% change in the

budget that the legislature finally enacts. This finding is consistent

with our conjecture that a full-time house has the patience to strengthen

its bargaining position against the governor, thus supporting the logic

of the staring-match model.

The results presented up to this point suggest that interbranch

negotiations over the size of the state budget are better conceptualized

using a staring-match model than with a setter model. Nevertheless,

one potential counterclaim is that the setter model may still be appropriate for the handful of states in which continuing resolutions are

allowed. We do not see, however, why this would be true. Remember

that continuing resolutions in those states that allow them are (at best)

short-term solutions—none can become permanent. Furthermore, their

use does not insulate the governor and legislature from the high political

and personal costs associated with a late budget. Continuing resolutions

operate quite differently at the national level. Continuing resolutions

are used by Congress and the president on well over half of all budget

bills, and they can be utilized for many months or longer (Meyers

1997). In fact, President Clinton and the Republican-controlled

Who Blinks First

75

TABLE 3

Governor’s Influence by Each Component

of Legislative Professionalism

Variables

Model 4

Model 5

Model 6

Model 7

Governor’s Proposal

.52**

(.07)

.83**

(.08)

.56**

(.07)

.80**

(.08)

Salary (in $1,000s)

.02

(.04)

__

__

.04

(.04)

Governor’s Proposal × Salary

–.001

(.002)

__

__

.005

(.003)

Session Length (hundreds of days)

__

–.002

(.53)

__

–.06

(.53)

Governor’s Proposal × Session Length

__

–.12**

(.02)

__

–.13**

(.02)

Staff per Member

__

__

–.19

(.43)

.02

(.45)

Governor’s Proposal × Staff per Member

__

__

–.01

(.01)

–.017

(.014)

% Democrat Legislature

–.06

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

–.06

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

Lagged Expenditures per Capita

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

Legislative Election Year

1.38

(.77)

1.64*

(.78)

1.44

(.77)

1.71*

(.76)

Unemployment Rate

–.47

(.36)

–.59

(.33)

–.51

(.36)

–.60

(.36)

Personal Income per Capita (in $1,000s)

1.04**

(.38)

.97**

(.36)

1.03**

(.37)

1.01**

(.37)

% Lagged Surplus

.06

(.64)

.02

(.06)

.06

(.06)

.01

(.06)

–6.83

(9.60)

–1.98

(9.36)

–5.39

(9.65)

–3.55

(9.76)

787

.30

787

.33

787

.30

787

.34

Constant

N

R2

Note: Estimated using state and year fixed effects.

**p < .01; *p < .05.

76

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

Congress, unable to reach a budget agreement in fiscal year 1999,

funded the federal government for the entire year using a series of

seven continuing resolutions (Davidson, Oleszek, and Lee 2007).

Still, we empirically tested whether or not the availability of

continuing resolutions affects gubernatorial power in Model 8. To do

so, we reestimated Model 5, this time including an interaction between

the governor’s budgetary proposal and a dummy for whether or not

continuing resolutions are expressly allowed. The results are presented

in Table 4. We found no meaningful effect. The coefficient on the new

interaction terms is negative and small in magnitude, and it fails to

even approach statistical significance. Because some states have no

legal provision regarding the use of continuing resolutions and no test

case (because of the lack of late budgets), we also made use of several

alternative codings. Specifically, we created dummy variables for states

where continuing resolutions may be allowed (those where continuing

resolutions are expressly authorized and those where there is no

provision regarding their use), states where a late budget triggers a

full government shutdown, and states where a late budget triggers either

a full or partial shutdown.19 These dummy variables are used in Models

9 through 11, with the results also shown in Table 4. Again we found

no effect. In each of these estimations, the interaction between gubernatorial budget proposals and legislative session length (the most

theoretically relevant component of legislative professionalization)

remains negative and statistically significant, providing additional

evidence that staring-match models are preferable to setter models for

conceptualizing state budget bargaining.

The Potential Endogeneity in Gubernatorial Budget Requests

It is also important to consider the extent to which state chief

executives have an incentive to misrepresent their preferences when

they submit their proposed budgets and whether or not this misrepresentation would bias our econometric results. Governors may, for instance, foresee legislative strength and adjust their budgetary proposals

accordingly. According to this logic, governors facing professional

legislatures would weaken their initial offers, moving closer to their

legislatures’ ideal points. Governors negotiating with citizen

legislatures would have no incentive to adjust their proposals, since

they should be able prevail in budgetary negotiations, given the institutional weakness of citizen legislatures.

We doubt, however, that governors frequently “game” their

budgetary proposals in this manner. When governors present their

Who Blinks First

77

TABLE 4

Governor’s Influence by Legislative Professionalization

and Status Quo Point

Variables

Model 8

Model 9

Model 10

Governor’s Proposal

.81**

(.08)

.85**

(.08)

.83**

(.09)

.81**

(.09)

Session Length (hundreds of days)

–.02

(.53)

–.03

(.53)

–.02

(.53)

–.01

(.53)

Governor’s Proposal × Session Length

–.10**

(.03)

–.10**

(.02)

–.12**

(.02)

–.12**

(.02)

Governor’s Proposal × Continuing

Resolutions Allowed

–.14

(.14)

__

__

__

Governor’s Proposal × Continuing

Resolutions May Be Allowed

__

–.15

(.10)

__

__

Full Shutdown

__

__

.002

(.10)

__

Full or Partial Shutdown

__

__

__

.03

(.09)

% Democrat Legislature

–.07

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

–.07

(.05)

Lagged Expenditures per Capita

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

–.01**

(.002)

Legislative Election Year

1.63*

(.76)

1.64*

(.76)

1.65*

(.76)

–1.64*

(.76)

Unemployment Rate

–.56

(.35)

–.57

(.35)

–.55

(.35)

–.55

(.35)

Personal Income per Capita (in $1,000s)

.97**

(.36)

1.00**

(.36)

.97**

(.37)

.97**

(.37)

% Lagged Surplus

.02

(.06)

.02

(.06)

.02

(.06)

.02

(.06)

–1.94

(9.36)

–2.04

(9.36)

–1.99

(9.38)

–2.06

(9.37)

787

.33

787

.33

787

.33

Constant

N

R2

787

.33

Note: Estimated using state and year fixed effects.

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Model 11

78

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

budgets, they send a signal to voters, interest groups, and campaign

contributors about their governing philosophy and legislative priorities.

Surely governors realize the signaling role of their actions and make

proposals accordingly. Moreover, the public is not likely to understand or appreciate complicated strategies, and officials may not be

able to explain them effectively. Such considerations should attenuate

any impulse the governor may have to game the proposed budget

(Denzau, Riker, and Shepsle 1985).

If, however, governors facing highly professionalized legislatures

do systematically move their initial budget proposals closer to their

legislatures’ ideal points, then the observed effect should be a stronger

relationship between executive proposals and enacted budgets. In other

words, the possibility of strategic misrepresentation should bias our

results against finding that governors are less powerful in states with

professionalized legislatures. This result is, of course, the opposite of

what our econometric estimations actually reveal. We have strong

evidence that governors are least powerful in states with these

legislatures. Thus, we are even more confident that the insight provided

by the staring-match model is correct and that initial gubernatorial

budget proposals are sincere.

To further satisfy skeptical readers, we empirically tested for the

possibility that gubernatorial budgetary proposals are gamed. These

results appear in the Appendix, available on the LSQ website <http://

www.uiowa.edu/~lsq/KousserPhillips_Appendix>. We examined

whether or not Democratic and Republican governors systematically

alter the size of their proposals when facing professional (that is, strong)

legislatures controlled by the opposition party. We did not uncover

any evidence suggesting that governors’ initial offers are shaped by

the strategic situations they face. Thus, we are confident that executive

budgetary proposals are not endogenous to states’ institutional

configurations.

Conclusion and Implications

Attempts to assess the budgetary influence of state legislators

and governors have traditionally relied upon spatial or setter models

of policymaking imported from studies of the U.S. Congress. In these

models, legislators, through their monopoly on proposal power and

their ability to credibly threaten to keep expenditures at the status quo

level, have substantially greater influence on budget making than

governors wield. This result contradicts numerous qualitative analyses

in the state politics literature that find that governors are the chief

Who Blinks First

79

legislators in the budgetary arena. We proposed and tested an alternative

simplification of state budgeting modeled on the games developed by

Rubinstein (1982, 1985) and Osborne and Rubinstein (1990) and

applied to states by Kousser (2005). Governors are quite potent in this

staring-match model, and the power of legislators declines when shorter

sessions or lower salaries make them impatient and willing to make a

deal.

Using an original dataset of gubernatorial budget proposals and

legislatively enacted state budgets, we explored the model’s predictions.

Overall, we found striking evidence of gubernatorial influence. Our

econometric estimations show that, across all types of legislatures, the

chief executive’s proposed budget has a positive and statistically

significant effect on the budget that is ultimately passed and signed

into law. Most important, however, the influence of legislators is closely

linked to levels of legislative professionalism. Legislators can drive a

particularly hard bargain when they typically hold long sessions; session

length is the component of professionalism most closely linked to the

theoretical concept of bargaining patience. This empirical relationship may be driven by something other than variation in patience: fulltime legislators might acquire more policy knowledge or political

acumen during their longer sessions, or full-time work might attract a

different type of legislator. Still, this finding is consistent with our

theoretical model and shows the importance of separating the session

length component from the staff and salary components. Just as Alt

and Lowry’s (1994, 2000) work demonstrated the centrality of state

institutions and party control in determining fiscal outcomes, our

empirical analysis reveals the power of governors and the important

mediating effect of legislative professionalism.

We believe that these findings yield three more-general lessons

for the study of bargaining between governmental branches. First, when

researchers apply formal models of bargaining, one size does not fit

all legislatures. Although setter models may capture the key dynamics

of federal budget bargaining in the U.S. Congress, where a continuing

resolution is a realistic reversionary outcome, these models do not

appear to fit well with states that demand that a new budget be passed

every year. Second, while variation in legislative professionalism

clearly determines legislative power, it is session length—more than

salary or staff—that appears to drive this trend. Isolating the theoretically distinct components of legislative professionalism can yield new

insights into this variable’s importance. Finally, directly measuring

governors’ preferences, rather than inferring them from party affiliations, demonstrates the significant influence that these preferences exert

80

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

over state policy. Overall, by closely examining the way that institutional contexts shape the strategies available to political actors, we

can uncover links between rules, political reforms, and bargaining

outcomes that may have implications for broader comparative studies.

Thad Kousser <tkousser@ucsd.edu> is Associate Professor of

Political Science, 9500 Gilman Drive, #0521, SSB 369, University of

California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0521. Justin H. Phillips

<jhp2121@columbia.edu> is Assistant Professor of Political Science,

IAB 7th Floor, 420 West 118th Street, Columbia University, New York,

NY 10027.

NOTES

1. The time series of legislative and gubernatorial approval in California reported

by the Field Poll reveals how severe these penalties can be. In the first two years of

Governor Gray Davis’s administration, 1999 and 2000, the branches reached budget

deals before the start of the new fiscal year. During Davis’s last two years, 2002 and

2003, negotiations dragged into September and August (Wilson and Ebbert 2006, 276).

In 1999 and 2000, the governor’s and the legislature’s approval ratings remained

essentially constant over the summer. But the legislature’s approval ratings dropped

from 45% to 35% from July to September of 2002 and from 31% to 19% from April to

July of 2003 (Field Poll 2004, 2). Davis’s already-low ratings edged downward as well

in each of those summers (Field Poll 2003, 3).

2. When the 2001 budget deal in New York was delayed, 84% of survey respondents were “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about the budget, and 63%

blamed both Governor Pataki and the state legislature (Quinnipiac 2001). In 2004,

81% of polled New Yorkers voiced concern over the state’s late budget, and 46% said

that it made them more willing to vote out incumbents (Caruso 2004).

3. When New Mexico’s budget was delayed in 2000, Governor Gary Johnson

and the legislative leaders all polled poorly and “New Mexico voters faulted Johnson

and lawmakers almost equally for their failure to reach agreement during the session

on a $3 billion budget” (“Voters Unimpressed with Johnson, Lawmakers,” Albuquerque

Journal, 19 March 2000, A1).

4. Unified government does not guarantee executive-legislative agreement over

the budget. In Massachusetts, for instance, Democratic governor Michael Dukakis

consistently had his budget rewritten by the legislature, which was overwhelmingly

controlled by his own party (Beyle 2004; Rosenthal 1990).

5. Our application of this model operates as a metaphor for the informal negotiations between the governor and legislative leaders—such as California’s “Big Five”

or Illinois’s “Four Tops”—that take place behind closed doors and allow either side to

initiate negotiations or to make detailed counteroffers. We believe that ignoring these

negotiations and focusing solely on budget bills and vetoes neglects the key dynamics

that drive interbranch bargaining.

Who Blinks First

81

6. By contrast, Alt and Lowry (1994, 813) specify the reversion point of their

model as follows: “If the legislature fails to make a proposal or if a proposal is vetoed

and the veto is sustained, then we assume that the budget is set equal to its reversion

level, which is the previous year’s expected levels plus any persistent effects of the

unforeseen shock.” Indeed, as we note, nine states explicitly permit continuing resolutions that would preserve the status quo in this way. But, we argue, even in these states,

preserving the status quo is no more attractive to the legislature than it is to the governor.

Whatever happens when a budget is late, whether it is a shutdown or a continuing

resolution, imposes high costs on both branches of government. The payoff that both

branches receive from the ultimate deal is eroded, preventing legislators from credibly

threatening to live with the status quo if the governor rejects their offer.

7. Since the Nash prediction is quite vague in this case—any division of the

dollar can be reached in the first round in equilibrium, because players can make threats

that are not credible—Osborne and Rubinstein (1990) employed Selten’s (1975) notion

of a subgame perfect equilibrium, which requires that best responses be played at

every point in the game that begins a subgame (see Morrow 1994). Subgame perfection generally refines the set of acceptable equilibrium strategies and, in this case,

generates a unique prediction.

8. Governors can exert influence over the size of government even in setter

models, as Alt and Lowry describe: “Divided cases produce target levels somewhere

between those of the parties” (1994, 820) and “In neither case does the legislature get

all it wants . . . as it must consider the threat of a veto” (2000, 1042). Nevertheless, the

power that governors have in a setter model is primarily negative; the veto gives them

the ability to put a break on high-spending legislatures. In our staring-match model,

the governor’s ability to make an offer to the legislature regarding the size of government gives the governor positive power to shape spending levels.

9. Legislatures in 30 states have the authority to call their own special sessions

(Council of State Governments 2000), but they are often forced to do so by a governor’s

veto. Although special sessions are not often called to resolve legislative-executive

conflicts, the threat of a special session is not unimportant. Delayed bargains are off

the equilibrium path of Rubinstein’s basic model, but they are weapons that do not

need to be unsheathed to be powerful.

10. Even the lowest-paid governor, Maine’s chief executive, earns $70,000 a

year (Council of State Governments 2005).

11. Interview by Thad Kousser, Salem, Oregon, July 8, 2001.

12. More than a month after New Mexico’s one-month session came to a close

without a budget deal, the governor called the state’s citizen legislators back to Santa

Fe for a special session. One legislator opined that such meetings “[C]ertainly are not

special. They are absolutely routine and, in my opinion, very annoying” (“Only Thing

Special about These Sessions Are Lessons,” Albuquerque Tribune, 4 April 2000, C-2).

In addition to exacting private costs, the session cost the legislature $45,000 a day to

run and generated political controversy. One legislator said, “I think it would behoove

all of us to be out of here by Saturday. I can just see a lot of really ugly newspaper

stories . . . if we’re still in session on April Fool’s” (Mark Hummels, “They’re Back,”

Santa Fe New Mexican, 28 March 2000, A-1). Perhaps because of their hurry, the

legislators passed a budget that was a “political home run” for the governor (“Vetoes

Enact Tax Reduction,” Albuquerque Journal, 22 April 2000, E-3).

82

Thad Kousser and Justin H. Phillips

13. In 2007, five of the six states in which a budget standoff dragged on past the

beginning of the next fiscal year—California, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and

Wisconsin—had professional legislatures that typically met at least 20 months in a

two-year biennium (personal communication between the authors and Arturo Perez of

the National Conference of State Legislatures). Historically, New York and California,

both of which have highly professionalized legislatures, have been plagued by late

budgets. As of fiscal year 2005, 20 of the last 21 budgets in New York were adopted

well after the legal deadline (McMahon 2005). Similarly, the governor and legislature

in California have failed to adopt a budget on time since fiscal year 1987 (California

Department of Finance 2007).

14. We tested a parallel set of models that used changes in real per capita spending,

rather than changes as a percent of past spending, to measure both the governor’s

proposals and final outcomes. The models yielded substantively identical results to

those presented here.

15. In a separate analysis, we interacted the governor’s proposal with the presence

of divided government, measured first by whether or not the party opposing the governor

controlled both houses of the legislature and second by whether or not the opposing

party controlled one legislative house. Neither interaction was statistically significant.

See analysis by Bowling and Ferguson (2001) and Ferguson (2003) for explorations of

the contingent effects of divided government on state legislative gridlock and the fate

of gubernatorial proposals.

16. Because we used fixed effects, we identified the effect of professionalization

in Models 2 and 3 by the variation in the size of the governor’s proposal.

17. Model 3b uses the dynamic professionalism scores reported by Squire (2007,

220–21). For observations up to fiscal year 1996, we used Squire’s 1986 scores. For

fiscal years 1996 through 2003, we used Squire’s 1996 scores. For the remaining years,

we used Squire’s 2003 scores. We also included professionalism by itself in this model