Industries, Products and Aggregations: Jack E. Triplett Brookings Institution

advertisement

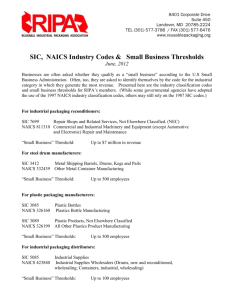

Draft: August 22, 2002 Industries, Products and Aggregations: NAICS Provision of Information for the New Economy Jack E. Triplett Brookings Institution Prepared for IAOS Meetings London, August 2002 Work on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) began in 1992, and it was completed before the term “new economy” came into use. However, NAICS design facilitated improvements in industry and product data that confront many of the issues at the center of the new economy discussion. There is no exact definition of “new economy,” nor need there be. The content of most of the new economy discussion concerns the impact of IT and ICT (Information Technology and Information and Communication Technology) on the economy (Bosworth and Triplett, 2001). Special interest adheres in those services industries and economic activities that are the most intensive users of ICT and where new products, new services and new methods of delivery are facilitated by investment in ICT equipment. In the former U.S. industry classification system (which was called the Standard Industrial Classification System, or SIC), and also in the international system, ISIC, many “new economy” activities were scattered around in different industries or else they were thrown together in one of the miscellaneous SIC “nec” (not elsewhere classified) categories. Failure in the old SIC system to distinguish new economy activities greatly inhibited economic analysis. Improvements in NAICS that facilitate analysis of new economy issues include the following. One example is the creation in NAICS of an “electronics” sub-sector in manufacturing, which brought together in one place most IT and ICT manufacturing. In the old SIC classification system, computers were combined in non-electrical machinery with drill bits, while semiconductors were placed in electrical machinery with Christmas tree lights. If the new economy meant that information technology had become a dominant contributor to economic growth, productivity, and the development of new products and new methods of distribution, then the analysis of the new economy required better and more coherent data on electronics manufacturing, which NAICS provided. A second example was the creation of an “Information” sector in NAICS (“Information and Culture” in Canada was the same NAICS sector, with a slightly different name). The information sector combined in one sector activities that did not fit well in the old and increasingly outmoded “goodsservices” distinction, and that were impacted strongly by information technology. A third example was the emphasis put in NAICS on better definition and finer delineation of services industries. Although many of these were not high tech services, still separating services industries—which are the most rapidly growing sectors of the economy— into finer and more homogeneous groupings provides a better basis for examining what is new. As a final example, the analytic materials released in the construction of NAICS contained a more clearly enunciated distinction between “industry” classification systems and “product” classification 2 systems, compared with the way those grouping systems had been handled in past classification systems, including ISIC and CPC. This distinction indirectly impacted the provision of information on the new economy, and is discussed more fully in a subsequent section of this paper. Actually, these most visible innovations in NAICS were the result of a more fundamental innovation: NAICS was the first industry (or other) classification system to be erected on an economic concept. In NAICS, establishments (productive units) are grouped into industries on the basis of similarities in their production processes. In contrast, in most other systems industries are determined by a mix of demand-side and supply-side reasoning, into which administrative, regulatory, and all sorts of political considerations are all too readily admitted. I. BACKGROUND. Some background provides perspective on the changes that NAICS made to existing industry classification systems, and the reasons for them. Around 1990, the U.S. statistical system came under severe criticism (one might even say assault) from its users and the press. National accounts, price indexes, and industry data were all criticized, but the old SIC system was singled out for special attention. Some press articles, after a citing a litany of complaints about the statistical system, contended that everything wrong with the U.S. statistical system could be laid at the feet of an inadequate industry classification. This, of course, was hyperbole. However, there was also a great amount of truth to assertions that the SIC system was inadequate. Moreover, many within the U.S. statistical system itself agreed that the SIC system needed drastic overhaul, especially for the technological sectors of a modern economy. A Census Bureau international conference (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1992) in late 1991, however, revealed no consensus on what should be done, beyond a strong consensus that the 1987 revision of the SIC system had been a disaster and that something must be done. The 1987 revision managed to break time series in disconcerting ways without creating obvious improvements to the classification system. Indeed, the essence of the SIC system was largely what it had been at its origin in 1940, and the very language used to describe it had been virtually unchanged for decades. In the face of the substantial turmoil and controversy over industry data, shortly after the Census Bureau conference Hermann Habermann, then head of the U.S. Statistical Policy Office, set up a new mechanism for redoing the U.S. Classification System and commissioned from it a “clean slate” rethinking of the whole system. The U.S., of course, has a decentralized statistical system. This new mechanism, known as the Economic Classification Policy Committee, or ECPC, actually decentralized decision making on the industry classification system, devolving it to the three major statistical agencies – the Bureau of Economic Analysis, represented by myself, the Census Bureau, represented by Charles Waite, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, represented by Thomas Plewes. Habermann also authorized an outreach to Canada and Mexico, which was a substantial break from past U.S. “go it alone” policy on industry classification systems. Inclusion of the other North American countries brought Jacob Ryten and Enrique Ordaz, from Statistics Canada and INEGI, respectively, onto the planning and decision making process and added their valuable and capable staff resources to the task. Additionally, the ECPC was charged with a substantial public outreach program, which we took seriously (outreach existed on paper before, but was more often evaded than honored)—this is discussed in a subsequent section. II. ECONOMIC PRINCIPLES FOR THINKING ABOUT CLASSIFICATIONS. In its “clean slate” approach to industry classifications, the NAICS planning effort did not begin with the hierarchy, as so often has been the case elsewhere. Instead, we began with the detailed industries. We took the position that we must first get the industries right and then group the industries into a hierarchy at the end. The process did not work entirely this way, but it was true that the final hierarchy of NAICS was only decided in a major international meeting at the very end of the project. The hierarchy in an industry classification system is important mainly because many statistical programs cannot support statistics for all of the detailed industries. Because of sampling or budgetary 2 3 reasons or because of disclosure problems if the industry is too small or too concentrated, detailed industries must sometimes be collapsed. When data for all of the industries are available, it is not important where an industry is put in the hierarchy, or even whether a hierarchy exists. An industry’s place in the hierarchy only matters when the industry must be collapsed with other industries into more aggregate groupings. Industries in NAICS are defined by a production concept: An industry (five or six digits in NAICS) is a grouping of productive units with the same or similar production processes. We adopted the production concept for several reasons. First, it makes theoretical economic sense (Triplett, 1990). Second, it made the whole system more coherent, which is more important than the theoretical niceties. I think all of the comparisons of NAICS with its predecessor SIC have concluded that NAICS makes more sense. Third, once understood, the production concept made it much easier to do the work, compared with methods used in previous classification systems (see below). Fourth, it put a stop to the invidious intervention of regulatory and administrative concerns, of union jurisdictions, trade association boundaries and so forth into an industry classification system that was meant for the production of economic statistics. Fifth, as the work proceeded, it turned out that the production side concept reduced greatly the inevitable national positioning and posturing that normally emerges in attempts to consolidate and rationalize international classification systems. International “politics” and other considerations. An example of the fifth point mentioned above is useful. One of the most contentious issues in the development of NAICS concerned the classification of what are known in the U.S. as “retail bakeries.” In the U.S., a small bakery that sells primarily on the premises was always classified in the retail trade industry. The Mexicans contended that all bakeries, including small ones, belonged in manufacturing, and this is where they were placed in the Mexican classification system. Although each country’s participants were no doubt motivated to an extent by the desire to preserve their own classification systems, the use of a production concept in NAICS meant that “we do it this way and you do it that way” was not a permissible way that an argument could be conducted. Instead, the Mexicans contended that the skills, equipment, and resources used in the baking part of the small bakery’s production activities were crucial and should determine its classification; the Americans contended that only a small part of the baker’s time was spent baking, while most of the shop’s resources went into operating the cash register and waiting on the customers. In the end, the Mexican position prevailed. But the point is: The arguments, analysis, and decision all revolved around economic analysis of the bakery industry, what it produced, and how it operated (which encompassed some differences in industry structures among the North American countries). It did not turn on extraneous administrative, legal or regulatory considerations, nor on the “you give us this one and we’ll give you that one” bargaining that reportedly emerged in other international classification projects. At one point, the head of the Mexican Statistical Agency, INEGI, told us that he was pleased that the NAICS negotiations were “so democratic,” as he put it. I responded that this was the case because we were arguing economic principles. This is an important lesson from NAICS that I believe others outside North America (and some inside it) have not understood. Use of an economic principle for classifications work greatly reduces the intervention of international politics, and facilitates reaching an agreement, one that, moreover, makes economic sense. Retreating to the outmoded bargaining regime in international discussions (convergence between European and North American classifications, for example) is a retrograde step that will diminish the value of everyone’s industry statistics. 3 4 An Economic Principle Makes Classification Work Easier. The operational advantages of constructing an industry classification system around a single, unifying economic concept have also not been understood outside of the people who worked on NAICS. With the NAICS production concept, only one set of issues was on the table: What is this industry’s production process? Information about what the industry does and how it does it was the only relevant information for deciding industry classification boundaries. Such information is not always easy to determine. But statistical agencies have a great amount of information about the nature of the industries they classify; gathering it is part of the task of constructing the statistics themselves, and is also a byproduct of the collection. They have less information about demands for products and about the nature of markets. The production concept had the incidental advantage of maximizing the relevance of exactly the information that the agencies had the most access to. Moreover, in conducting its public outreach program in the U.S., the ECPC asked that people who were proposing new or modified industries explain as part of their proposal how the proposed industry’s production processes differed from those of existing industries. This generated useful information that supplemented internal statistical agency knowledge. In contrast, when industry classifications are not constructed using an economic concept, everything is on the table. When everything is on the table, then every argument must be considered because there is no single classification concept to determine what is relevant and what is not. It is much harder to carry out the analysis because everything, in principle, matters, and it is accordingly much harder to reach agreement. Moreover, when everything is on the table, inevitably one decision gets made on one principle and another decision on some other principle, and the result is an industry classification system that lacks coherence. Many people, including many of those who worked on NAICS, were quite surprised to find that having an economic concept made the work easier, not harder. It is an important lesson that can be extended to other work, especially international work, on industry classifications. An Economic Principle Reduces Political and Administrative Interference in the Classification System. In past U.S. SIC revisions, public proposals were always a part of the process. However, many persons who submitted proposals told me that they felt that their proposals went into a room with the “bureaucrats,” and they never learned why their proposals were rejected. Additionally, private stories abounded of decisions that reflected some political reality or other, though I think those cases were always small as a proportion of the total decisions. I can understand why dialog with users was minimal in the past. Without an economic concept, there was no answer when the XYZ trade association asked why its proposal was not accepted when the proposal from the ABC trade association was. Government representatives were therefore reluctant to enter into detailed discussion with interested parties. The more that was said about the process and the reasons for classification decisions, the more the public dissatisfaction and the greater the controversy, so a minimal amount was said. Lack of dialog caused lack of trust in the SIC administrative process, and lack of respect for the integrity of its product. In NAICS, we did exactly the opposite: We talked with every industry group that would give us a hearing. We actively solicited proposals. We also told them what we would consider and what we would not consider, and why. We would consider proposals for new industries or alterations of existing industries on the basis of differences in production processes between the producing units involved, and we would not consider anything else. Moreover, we published a series of “Issues Papers” that explained our conceptual deliberations, and we published sections of NAICS for comment as they were ready. These publications maximized the public review of the new classification system, rather than minimizing it, as had been previous practice in the SIC 4 5 Outreach to industry and other user groups had two purposes and benefits: First, we were building trust and gaining support for what we were doing. Second, we were obtaining input that could be valuable in constructing NAICS. Not incidentally, however, more public outreach and more public explanation of the production concept adopted for NAICS meant less political and administrative interference in the classification decisions, not more. Talking about the process--when it is built on an economic concept--does generate more public interest in the classification effort, but does not generate more political pressures; rather, it insulates against political pressure. An anecdote illustrates. At one point, a political appointee in the Department of Commerce decided that he did not like plans for NAICS and asked the numerous industry advisory committees in his part of the department (which did not house the statistical agencies) to intervene. We simply used these industry advisory committee meetings as another forum in which we could explain what we were doing and where we could ask for aid. I recall one such meeting where industry experts explained recent technological changes within their industry, which implied that one proposal that we were entertaining did not meet our objectives. The meetings were valuable to us. In the end, the industry advisory committees agreed with what we were proposing in NAICS and not with the political official who raised questions. It is true that we had to be able to explain the economic concept that was adopted for NAICS and the reasons for it, but we were doing that anyway. Furthermore, it is good practice: No statistical agency should institute changes that it cannot explain to its users. In NAICS, the previous anecdote represented a rare event, not the norm. I am sure the reason why we were subjected to very little political pressure is our adoption of a concept, so we could explain our decisions and why we made them. My impression, from talking to people who do classifications in other countries, is that few industry classifications programs try to get input from user groups. In my experience, this fails to grasp a public input that can be valuable. The CLAMOUR report (UK ONS, 2002) suggests that user input would be valuable in Europe, for example. III. NAICS INFORMATION SECTOR. I have already noted that in the construction of NAICS the hierarchy was mostly established toward the end. The Information sector (NAICS sector 51) was an exception to that rule. A number of problems with the old system that came up early in the NAICS process made it clear that a new hierarchical element needed to be devised that lay between the old “goods and services” categories. In the end, we decided on a new NAICS sector, which we called “Information” (in Canada, Information and Culture), which encompassed a group of emerging and growing industries. One aspect of NAICS that was different from other similar efforts was a decision to publish rationales for what was done, documentations of the analysis that went into definitions of NAICS industries and sectors. These rationales were incorporated into the three country agreements that were published as the work proceeded (another break from the past), and eventually, in condensed forms, in the NAICS manuals (OMB, 1998). A study by Daniel April of Statistics Canada was very influential in the definition of the information sector as finally adopted in NAICS, and revised text from his paper is incorporated into the description of the NAICS Information sector (OMB, 1998, pages 495-96). Some SIC classifications were incredibly out of date. In the old classification system, newspaper reporters were manufacturing workers because the publication of a newspaper was regarded as simply an adjunct to the printing process. That might have made some marginal sense in a day when newspapers were written and printed in the same establishment, but that is seldom the case today. Indeed, newspapers are increasingly accessed online, so that the whole printing process has become irrelevant for a portion of the distribution of news from its producers to its readers. 5 6 We decided that “publishing,” as applied to newspapers, books and magazines, meant the design, creation and bringing to market of an information product. It did not depend on the way the information product was subsequently manufactured, or whether it was manufactured at all, nor did it depend on the precise method for distribution of the information product. Manufacturing, if it took place at all, would be determined by the production process involved, not whether the product was an information product. Similarly, distribution processes would be classified by their own production processes, not whether distribution involved an information product. For example, mail distribution, truck-carrier distribution (for newspapers, for example) and on-line distribution are three different processes for distributing published books and newspapers; in NAICS, they were kept separate in order to provide statistics for tracking changes in distribution technology, they were not combined in some manner on the grounds that they all distributed products having similar end uses. With the definition of publishing adopted for NAICS, we proposed that it also applied to the design, construction and bringing to market of software products. Somewhat to our surprise, when we proposed this to representatives of the software industry, they agreed enthusiastically with us. In the old SIC classification system, software that is put on a disk in a manufacturing plant (that may also produce music records and related materials, which were in manufacturing) was wrenched into business services on the grounds that it served a similar function as custom software. Programming is involved in both cases, of course, but the rest of the production process is quite different. There is very little overlap between establishments in the custom software business and those in the software publishing business. If the newspaper, or the software, is distributed online, there may be nothing tangible that resembles the normal definition of a “good.” Moreover, if the distribution of newspapers or of software were to become increasingly electronic and not physical, one needed industry statistics to understand that. One could not understand it if the separate production and distribution processes were pushed together (as in the old classification system) on the grounds that they somehow served similar purposes. Having separate information about custom software and “shrink wrap” software—and about software that goes through a manufacturing process to put it on a disk before it gets to the user and software that does not—helps to understand changes in production, in new products, and in distribution. These change are the essence of the “new economy” discussion. An industry classification should be set up to make these changes in the economy clear, and not to obscure them. The description of the NAICS Information sector (OMB, 1998) notes a number of properties in which industries in the Information sector differ from those in either goods or in services. Unlike goods, the commodity produced by information industries does not necessarily take on a tangible form, and unlike services, they do not necessarily require direct contact with the customer. The production processes are quite different, in most cases, because what is at issue is a right, sometimes protected in the form of a copyright or other process. Also, distribution processes for the commodities produced by information industries differ widely and are changing very rapidly. A short time after we made the NAICS Information sector decision, the New York Times began a regular Monday business section special coverage that it called “Information Industries.” It was interesting to us that what the New York Times included in its list of information industries was very similar to what we had included in the NAICS Information sector. We had designed a sector that would be useful. It is also worth emphasizing what we did not put in the Information sector. At the time we were designing the Information sector, it was quite common to read statements such as: “In a modern economy there is a great amount of information in the production of a pair of shoes.” There is some sense in which that is true, information is important nearly everywhere. The NAICS Information sector was not intended to define the industries in which information was important, because that would include nearly everything in the economy. We called it “Information,” but that does not imply that industries outside the information sector do not use information. We constructed a limited sector, deliberately. 6 7 The description of the NAICS Information sector (OMB, 1998, pages 495-96) provides the rationale for this limited sector. “For the purpose of developing NAICS, it is the transformation of information into a commodity that is produced and distributed by a number of growing industries that is at issue.” The text goes on to note: “These activities were formally classified throughout the existing national classifications. Traditional publishing is in manufacturing; broadcasting in communications; software production in business services; film production in amusement services; and so forth. The unique characteristics of information and cultural products, and of the processes involved in their production and distribution, distinguishes the information sector from the goods-producing and serviceproducing sectors.” I frequently hear of proposals to add industries to the NAICS information sector (for example, in international discussions of the future of ISIC). Nothing is set for all time. But some of these proposals seem to have overlooked the published justification and rationale for setting up the NAICS information sector in the first place. We might want to modify those principles in some future classification system. Proposals for adding to the definition of the NAICS Information sector need to be accompanied by statements of how they better fit the rationale than does the existing definition of the sector, or by a modified or updated rationale that is better and into which the new proposals fit. I am not asserting that no improvements can be made, for improvements always come with increased understanding and are necessary to reflect changes in the economy. Rather, I am emphasizing the conceptual nature of the decisions in NAICS and repeating the point that changes in the classifications need to be made in some framework of conceptual reasoning that is comparable to the one used in NAICS. IV. WHAT SHOULD WE HAVE DONE DIFFERENTLY? Andy Wyckoff asked me to reflect on what, in retrospect, I would have done differently. It is nearly ten years since we began the process of constructing NAICS, the economy has changed in that time and of course with changes, an industry classification system must be updated. But that is not what I want to talk about. Rather, what should we have done with the information that was, or should have been, available to us at the time? There are three glaring deficiencies in the implementation of NAICS. The Industries Themselves. In retrospect, we did no go far enough in constructing NAICS on a production concept. For example, there is no biotech industry in NAICS. One critic of NAICS remarked that had Dolly, the cloned sheep, been cloned in North America, there is no industry into which she fit. There is no industry in ISIC or NACE either, but the point was well taken. The technological ferment in biotech, nano-tech, and other emerging high tech industries simply did not get into NAICS (some were proposed), for good reasons and for bad. Additionally, I looked at data on medical equipment recently (Triplett and Gunter, 2001). The industry in NAICS is a mess. It was carried over virtually intact from the old SIC, and contains a muddle of demand side and production side groupings in which high tech and low tech production is combined with little coherence, yielding data of minimal usefulness. We should have reconstructed it on a more sensible basis. Other examples no doubt exist. One reason that we did not overhaul as many existing SIC industries as we probably should have was resources and time. The work was exhausting, and for internal reasons in Mexico almost all of the manufacturing work was conducted in Aguas Calientes with many of the U.S. and Canadian participants away from their homes for long periods of time. But there was another reason. Although in principle we started with a clean slate, we really did not. Data for existing industries were published. Breaking time series is costly, and should not be done without strong justification. We said that in the documentation of NAICS (ECPC, 1993a). As the NAICS work proceeded, we came under strong pressure from one U.S. statistical agency in particular to minimize the number of time series breaks in the transition between the old SIC and the new NAICS. We probably over-responded to that pressure. Somewhere in the middle of the NAICS process, we adopted a rough rule that said manufacturing industries would only be changed if there was some outside proposal, formal or informal, to do so, or if change was required to reach international comparability. No 7 8 outside user proposed either a biotech industry or separating medical equipment to more adequately distinguish high tech electronic equipment like scanners from more ordinary devices, and neither industry was prominent in Canada and Mexico. So in the end, the past history of classifications constrained changes, as indeed it should. But in my view, the push from within the U.S. statistical system to retain time series “comparability” of poor quality data got too much weight. Insufficient Overlap. To minimize user disruption because of the inevitable time series breaks, the initial ECPC plan envisioned at least two overlaps (1992 and 1997) for which U.S. industry data would be tabulated on both the old SIC and the new NAICS system. Budget problems in the Census Bureau intervened, and only a 1997 overlap was calculated. Researchers at the Center for Economic Studies are slowly re-tabulating the 1992 Economic Census for research purposes. This 1992 overlap should always have gotten a much higher priority. This was indirectly a consequence of decentralization of the U.S. system, which has no over-arching budgetary authority to review and correct deficiencies such as this one. Uncoordinated Implementation. Finally, the worst problems created by the introduction of NAICS in the U.S. come directly out of its decentralized statistical system. One agency, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, decided to implement NAICS on a much slower schedule than did the others. Indeed, the BLS has still not implemented NAICS. There were indeed some problems that needed to be surmounted, but in the end I believe this was just abysmal decision making. It has imposed substantial costs on users of industry data, including other statistical agencies such as the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which must combine data from different agencies in the national accounts. It never would have happened in a centralized statistical system (it did not happen in Canada or Mexico). It happened in the U.S. because in the U.S. there is no decision-making authority at the center. Frankly, the situation is a scandal and it could have been and should have been avoided. V. COMMODITY OR PRODUCT CLASSIFICATIONS. Finally, I want to add a few words about the topic of product classifications. This topic has become greatly confused. The ECPC made a distinction between industry classification systems, which group producing units by similarities in their production processes, and product classification systems that group the products of those production processes. We called the latter “product grouping systems” for lack of a better word, but it is not a very good term. We explained that what we meant were groupings of products that corresponded to markets (ECPC, 1993b).1 Industry classification systems always contain lists of products that are the outputs of the production processes used in the industry. Industries are defined by similarities in their production processes but we know what they produce by the list of products that accompanies every industry classification system. The lists of products are important, both for their own purposes (much data is collected on products, price indexes for example) and for classifications work itself. Indeed, NAICS set in motion a project to define the products of services industries, because product lists in those industries were quite backward and underdeveloped, compared to those for goods-producing industries, which had many years’ head start. For many purposes, one needs output data on the products of each industry, not just the aggregate industry output, so defining the products of services industry was a vital step toward improving information about services production. From the ubiquity of product lists in industry classifications, it is sometimes thought or said that industry classification systems group products. That is not correct. Industry classification systems group producing units, that is, they group units for purposes for which outputs and inputs must be used together. “Commodities or services that serve similar purposes, that are used together, or that are functionally related in use, are grouped together.” ECPC Issues Paper No. 1, page 12 (ECPC, 1993b). 1 8 9 A product grouping system is not the same as the list of products that go into the industry classification system. An example illustrates. One often hears calls for a “tourism industry.” We heard it in the construction of NAICS. Tourism is not an industry as we used the term “industry” in NAICS. An industry system groups producing units, it groups both the outputs of the industry and its inputs. A restaurant may serve tourists, and we might determine from some source how much tourists spend on restaurants in a particular city or area. But there is no way that one can go to a restaurant and ask: What part of the chef’s time is spent satisfying demands of tourists? Moreover, no one (or nearly no one) is interested in such a statistic, and if there were interest, it is properly satisfied with an analytic statistic or estimate, not with a collected statistic. Tourism is instead a product grouping system. Finding out the products that go into a tourism grouping is a sensible activity and estimating the expenditures by tourists on those tourism products is also a sensible activity, which provides useful information for some purposes. Rather than saying to this valid statistical need that it could not be provided because “tourism” was not an industry (which had been said before), the ECPC said that information on tourism should be provided in the U.S. as part of a product grouping system. There are many product grouping systems. Unlike the industry system in which each producing unit goes into one and only one industry (for reasons that I cannot elaborate here but that are obvious ones), product grouping systems can readily overlap. One might put restaurant meals in a tourism product grouping system and at the same time into an entertainment product grouping system and (perhaps) a healthy living product grouping system. An individual product can go into many different product groupings, if it is appropriate to do so. Product grouping systems can cut across industries; they are not constrained in any way by industry boundaries. Product grouping systems conform to markets, not to industry boundaries. Moreover, there is no need to have product grouping systems that exhaust the output of the entire economy. The objective of a product grouping system is not the same as the objective of an industry system. Indeed, the ECPC proposed that product grouping systems would be constructed in the U.S. only in response to requests of users (at the time the NAICS work was underway, Canada and Mexico did not commit to provide product grouping data). Because of the exigencies of completing NAICS, work on product grouping systems was pushed off. It has been revived in North America. But it should not be revived as some sort of mirror image of an industry grouping system. The two are not connected; they have different purposes and requirements, and different structures. A product grouping system, or really a group of product grouping systems, needs to be thought through from the standpoint of the marketing use of the data they provide. That process is, regrettably, some way off. 9 10 References Bosworth, Barry P. and Jack E. Triplett. 2001. “What’s New About the New Economy? IT, Economic Growth, and Productivity.” International Productivity Monitor. Number 2, Spring. Economic Classification Policy Committee. 1993a. “The Impact of Classification Revisions on Time Series.” Issues Paper Number 5. Available at: http://www.census.gov/epcd/naics/issues5 Accessed August 20, 2002. Economic Classification Policy Committee. 1993b. “Conceptual Issues.” Issues Paper Number 1. Federal Register, March 31, 1993. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, pp. 16990-17004. Available at: http://www.census.gov/epcd/naics/issues1 Accessed August 20, 2002. Office of Management and Budget. 1998. North American Industry Classification System: United States, 1997. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President : Office of Management and Budget. Triplett, Jack E. 1990. “The Theory of Industrial and Occupational Classifications and Related Phenomena.” Bureau of the Census 1990 Annual Research Conference: Proceedings. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, August. Triplett, Jack E. and David Gunter. 2001. “Medical Equipment.” Presented at the Brookings Workshop on Economic Measurement: The Adequacy of Data for Analyzing and Forecasting the High-Tech Sector, October 12. Available at: http://www.brook.edu/dybdocroot/es/research/projects/productivity/ workshops/20011012.htm United Kingdom Office of National Statistics. 2002. Clamour Final Report. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/methods_quality/clamour/downloads/final_reportv1.doc Accessed August 22, 2002. United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. 1991 International Conference on the Classification of Economic Activities--Proceedings, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1992. 10