LATINOS, ANGLOS, VOTERS, CANDIDATES, AND VOTING RIGHTS J N

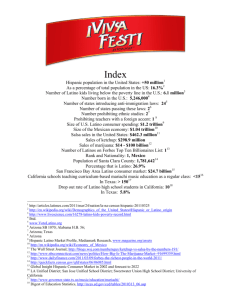

advertisement