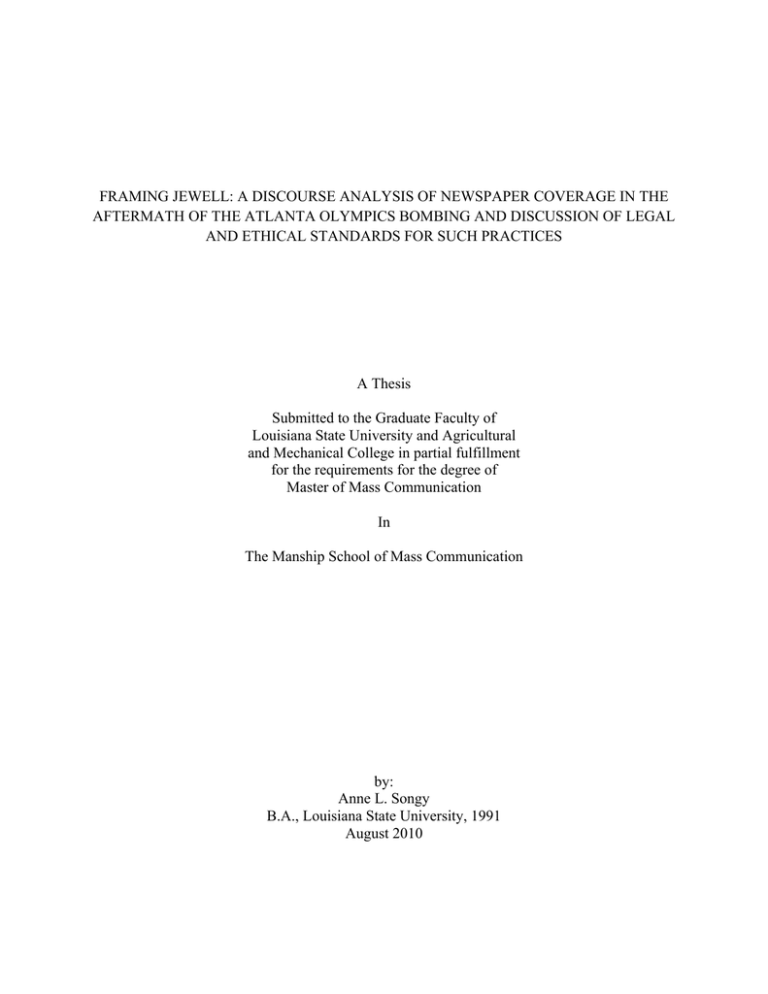

FRAMING JEWELL: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF NEWSPAPER COVERAGE IN THE

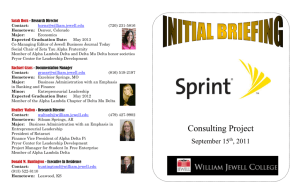

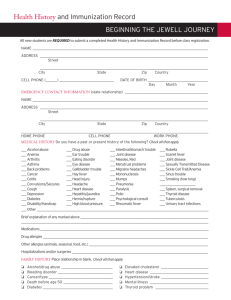

advertisement