Document 10290713

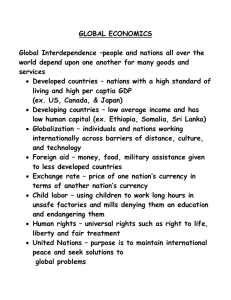

advertisement