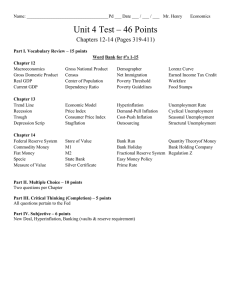

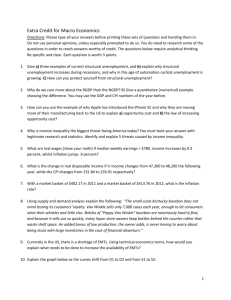

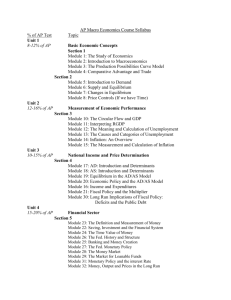

Responses Price Shocks Macro

advertisement