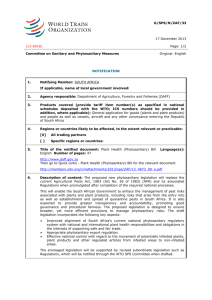

Quantification of Sanitary, Phytosanitary, and John C. Beghin and Jean-Christophe Bureau

advertisement