Document 10288827

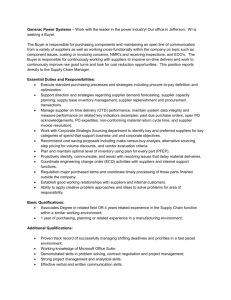

advertisement