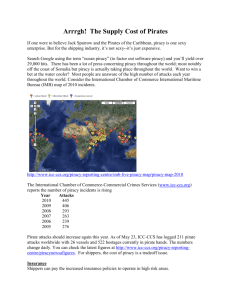

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

advertisement