Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World

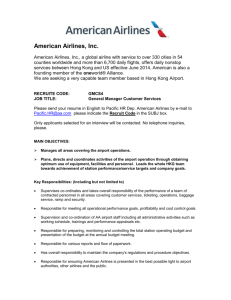

advertisement