STRUCTURE OF THE CHLOROPLAST AND ITS DNA IN CHLOROMONADOPHYCEAN ALGAE

advertisement

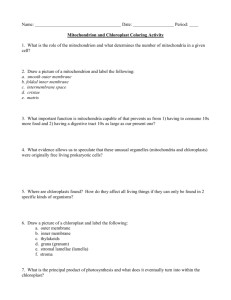

J. Cell Set. 49, 401-409 (1981) Printed in Great Britain © Company of Biologists Limited 1081 STRUCTURE OF THE CHLOROPLAST AND ITS DNA IN CHLOROMONADOPHYCEAN ALGAE ANNETTE W. COLEMAN AND PETER HEYWOOD Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02912, U.S.A. SUMMARY The arrangement and ultrastructure of chloroplasts is described for the Chloromonadophycean algae Gonyostomum semen Diesing and Vacuolaria virescens Cienkowsky. The chloroplasts are present in large numbers and are discoid structures approximately 3-4 /im in length by 2-3 /i-m in width. In Gonyostomum semen the chloroplasts form a single layer immediately interior to the cell membrane; frequently their longitudinal axis parallels the longitudinal axis of the cell. The chloroplasts in Vacuolaria virescens are more than 1 layer deep and do not appear to be preferentially oriented. In both organisms, chloroplast bands usually consist of 3 apposed thylakoids, although fusion and interconnections between adjacent bands frequently occur. External to the girdle band (the outermost thylakoids) is the chloroplast envelope. This is bounded by endoplasmic reticulum but there is no immediately apparent continuity between this endoplasmic reticulum and the nuclear envelope. Electron-dense spheres in the chloroplast stroma are thought to be lipid food reserve. Ring-shaped electron-translucent regions in the chloroplast contain chloroplast DNA. The DNA is distributed along this ring in an uneven fashion and, when stained, resembles a string of beads. Each plastid has 1 ring, and the ring is unbroken in the intact plastid. INTRODUCTION Some features of chloroplast ultrastructure in the Chloromonadophyceae have been described in previously published accounts of these algae (Heywood, 1977, 1980; Koch & Schnepf, 1967; Mignot, 1967, 1976). The purpose of this paper is to describe the chloroplasts of Gonyostomum semen and Vacuolaria virescens in greater detail and to correlate these findings with observations on light-microscope preparations in which the chloroplast DNA has been rendered fluorescent with 4',6-diamidino -2-phenylindole (DAPI). MATERIALS AND METHODS Unialgal cultures of Gonyostomum semen and Vacuolaria virescens were grown at 18 ± 1 deg. C on defined medium (Heywood, 1973), which was aerated with a gas mixture of 4 % C0 2 in air, or in soil/water tubes lacking CaCO3 supplementation. Illumination (2000 lx) was supplied by Ecko daylight fluorescent tubes either continuously or intermittently (16 h light alternating with 8 h dark). Olisthodiscus luteus was grown in f/2 medium (Guillard, 1975) at 24 °C in 1000 lx fluorescent light. 402 A. W. Coleman and P. Heywood Chloromonadophycean chloroplasts 403 For electron microscopy, cells harvested by gentle centrifugation were fixed for 1 h in a 2 % solution of glutaraldehyde buffered with 0-07 M-phosphate buffer at pH6'S. After several washes in buffer they were post-fixed in buffered 1 % osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in Epon. Light microscopy of cells prepared in this manner utilized io-/tm thick sections, which were examined with Nomarski differential interference optics (e.g. Fig. 2). Ultrathin sections were cut with a diamond knife, stained with aqueous uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using a Philips 201S electron microscope (e.g. Figs. 1, 3-18). Ribbons of serial sections were collected on single-hole copper grids coated with Formvar and carbon. Observations of chloroplast DNA were made in situ using fluorescence microscopy of cells stained with the DNA-binding fluorochrome, DAPI, with or without prior enzyme treatment as described by Coleman (1979). Chloroplasts isolated into the H medium of Shepard (1970) were vitally stained with 0-5 /ig/ml DAPI and observed directly with an epifluorescence microscope. Similar staining (0-5-0-1 /tg/ml DAPI in Mcllvaine's buffer, pH 4-0) was applied to cells or isolated plastids, variously manipulated, that had been pressed beneath a cover slip onto gelatin-coated slides, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and fixed in 3 :1 (ethanol: acetic acid) or in 70 % ethanol. OBSERVATIONS Gonyostomum semen and Vacuolaria virescens are biflagellate unicells that frequently reach 60-80 /tm in length. The cells contain 200-500 chloroplasts, which are approximately 3-4 /tm in length by 2-3 /tm in width and are disk-shaped or plano-convex (Fig. 1). In Gonyostomum semen the plano-convex chloroplasts usually have their flattened surface adjacent to the cell membrane (Heywood, 1968; Hovasse, 1945); in this organism the chloroplasts form a single layer immediately interior to the cell membrane (Fig. 2) and frequently their longitudinal axis parallels the longitudinal axis of the cell (Heywood, 1968; Hovasse, 1945), but this is not always the case (Mignot, 1976). In Vacuolaria virescens the chloroplasts are several layers deep and do not appear to be oriented in any particular direction (Fig. 1). Chloroplast bands are arranged approximately parallel to the longitudinal axis of the chloroplast; frequent interconnections exist between adjacent bands (Fig. 3). Each band consists of 3 thylakoids. The girdle band, which forms the periphery of the chloroplast, has the same structure as the other bands and is often in continuity Fig. 1. Section through a cell of Vacuolaria virescens. Chloroplasts occur between the cell membrane and the layer of cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus (n). Also present is an extensive Golgi region (g), which is adjacent to the contractile vacuole (cv). x 4000. Fig. 2. Two cells of Gonyostomum semen photographed using Nomarski differential interference microscopy. The cell on the left is in oblique longitudinal section while the cell on the right is in transverse section. The chloroplasts (c) occur as a single row immediately interior to the cell membrane and a nucleus (n) is also present, x 1000. Fig. 3. A chloroplast of Gonyostomum.semen. Note the lipid droplet (/) and the interconnections between bands (1) and between bands and the girdle band (arrowheads). External to the girdle band (g) are the chloroplast envelope and endoplasmic reticulum (ce/er). x 25 000. An electron-translucent region of the chloroplast occurs immediately adjacent to the girdle band; this region (solid arrow) is shown at higher magnification in the inset. It contains fine fibrillar structures (open arrow) which are presumptive chloroplast DNA. The second inset (from another chloroplast) also shows this same type offibrillarstructure. Inset magnification is x 80000. A. W. Coleman and P. Heywood 8 Chloromonadophycean chloroplasts 405 with them. The chloroplast stroma contains large numbers of small electron-opaque structures, which are assumed to be chloroplast ribosomes. Also present in the stroma are osmiophilic spheres (Fig. 3), which are thought to be a lipid food reserve. Pyrenoids occur in Chattonella subsalsa (Mignot, 1976) but they appear to be absent in Gonyostomum semen and Vacuolaria virescens. Eyespots have not been observed but the cells are positively phototactic towards light of moderate intensity (Chapman & Haxo, 1966; Poisson & Hollande, 1943) and a diurnal movement has been reported in natural populations of Gonyostomum semen (Cowles & Brambel, 1936). External to the girdle band is the chloroplast envelope, which is bounded by endoplasmic reticulum (Figs. 3-15). Presumably the latter helps to maintain the chloroplast in position and also ensures some degree of membrane contact between the chloroplast and other organelles, but a direct continuity between the nuclear envelope and this endoplasmic reticulum is not apparent. Longitudinal sections through chloroplasts frequently reveal the presence of an electron-translucent region immediately interior to the girdle band (Figs. 3-18). This region lacks chloroplast bands and resembles the ring-shaped chloroplast nucleoids in the Bacillariophyceae, Chrysophyceae, Phaeophyceae and Xanthophyceae (Bisalputra, 1974; Gibbs, 1970; Taylor, 1976). Serial sections (Figs. 4-15, Figs. 16-18) confirm that this electron-translucent region is a continuous structure, and indicate that its width is variable (compare Figs. 6, 7 with Fig. 8 and Figs. 11—13 with Figs. 14, 15). The electron-translucent region contains irregularly arranged fibrils, which resemble DNA in morphology and dimensions (Fig. 3). Confirmation of the presence of chloroplast DNA is provided by examining Vacuolaria (Fig. 19) and Gonyostomum (Fig. 21) cells stained with DAPI, a fluorochrome with high affinity for double-stranded DNA. Both in isolated, unfixed chloroplasts and in fixed material there is 1 ring of DNA per plastid (Fig. 22). The normal, nodulated appearance of the ring is shown clearly in Figs. 19-21. The physical continuity of this complex nucleoid is apparent when a ring isolated from a plastid is stretched before fixation (Fig. 23). Fixed preparations treated with DNase and then stained fail to reveal any such rings, while pretreatment with RNase or trypsin leaves the rings intact, as detected by DAPI staining. Similar brightlystaining rings can be observed in Olisthodiscus (Fig. 24). Figs. 4-15. Serial sections through one end of a chloroplast of Vacuolaria virescens. Fig. 4 is a section close to one side of the chloroplast while Fig. 15 is an approximately median longitudinal section. The asterisk in Fig. 4 has been placed in the electrontranslucent structure adjacent to the girdle band. Successive sections indicate that the electron-translucent region is a continuouus structure whose width is variable. Chloroplast DNA is not distinguishable in these micrographs. The chloroplast envelope and its surrounding layer of endoplasmic reticulum (ce/er) occur exterior to the girdle band (g) and are usually in close apposition, but these layers can be distinguished in Fig. 14. x 23 300. Figs. 16-18. Serial sections through one side of a chloroplast of Vacuolaria virescens. The asterisks in Fig. 16 have been placed in the electron-translucent structure adjacent to the girdle band. A few chloroplast bands are present in Figs. 16, 17 but these are absent in Fig. 18, which is a glancing section through the girdle band and the electron-translucent region immediately interior to it. x 18000. A. W. Coletnan and P. Heywood 406 19 Fig. 19. Montage of squashed Vacuolaria virescens cell, fixed and treated with RNase prior to staining with DAPI. Fluorescence photomicrograph reveals a large, pawshaped structure, the broken nucleus, and many chloroplast DNA rings spread about, some slightly stretched. Bar, io/(m. x 700. Fig. zo. Fluorescent chloroplast DNA rings from isolated Vacuolaria plastids, pretreated with RNase and then stained with DAPI. Beaded aspect is characteristic, x 1700. Fig. 21. DAPI fluorescence photomicrograph of squashed, stained cell of Gonyostomum semen, illustrating bright centrally-located nucleus and surrounding plastid DNA rings. Bar, 10 fim. x 1400. Fig. 32. A (fluorescence) and B (phase contrast) photomicrographs of a field of isolated Gonyostomum chloroplasts, fixed in 70 % ethanol to retain the characteristic plastid phase density, and stained with DAPI. Each plastid contains one DNA ring, seen here either in face or edge view, x 2000. Fig. 23. Fluorescence photomicrograph of stretched DNA rings from isolated Gonyostomum plastids, fixed and stained with DAPI. Longest ring visible is 55 fim in circumference, x 1000. Fig. 24. Whole cell of OHsthodiscus, slightly squashed, fixed and stained with DAPI. x 1200. Chloromonadophycean chloroplasts 408 A. W. Coletnan and P. Heywood DISCUSSION Chloromonadophycean chloroplasts are often a distinctive bright green colour (Drouet & Cohen, 1935; Poisson & Hollande, 1943). The presence of chlorophylls a and c has been demonstrated by Guillard & Lorenzen (1972), and features of their structure are shared by 4 of the 5 other major algal groups that possess these chlorophylls, the Bacillariophyceae, Chrysophyceae, Phaeophyceae and Xanthophyceae. In particular, the Chloromonadophyceae resemble these algae in the possession of a ring-shaped electron-transparent region immediately inside the girdle band. Fibrils that resemble DNA in morphology and dimensions (Fig. 3) occur in this region. The presence of 1 ring of DNA per chloroplast has been demonstrated in both Gonyostomum semen (Figs. 21, 22) and Vacuolaria virescens (Fig. 19). Similarly, there is one ring of DNA per chloroplast in Olisthodiscus (Fig. 24), an organism which may be a member of the Chloromonadophyceae (for a discussion of this point see Gibbs, Chu & Magnussen, 1980, and Loeblich & Fine, 1977). Fluorochrome staining has revealed similar rings in diatom and brown algal cells (Coleman, 1979). Biochemical evidence suggests that the chloroplast nucleoid in Olisthodiscus is multiploid (Cattolicco, 1978; Aldrich & Cattolicco, 1979), and preliminary microspectrophotometric evaluation of the Gonyostomum plastid DNA ring suggests a similar situation (Coleman, unpublished observations). This multi-genome state of the plastid in organisms with ring-shaped DNA nucleoids is analogous to the situation in green algae and higher plants, where the plastid DNA is also multiploid (reviewed by Herrman & Possingham, 1980). In this latter situation, DNA aggregates can be seen irregularly dispersed among the thylakoids stacks; the possible continuity of the various DNA centres within a single plastid has not yet been established. We are grateful to Dr R. R. L. Guillard for the gift of an Olisthodiscus luteus culture, and to Mr Mark Maguire for his dedicated assistance. This investigation was supported by a Biomedical Sciences Support Grant from Brown University and by NSF Grants DEB-76-82919, PCM 78-15783 and PCM-79-23054. REFERENCES J. & CATTOLICCO, R. A. (1979). Characterization of chloroplast DNA from Olisthodiscus luteus. J. Phycol. 16, 6A BISALPUTRA, T. (1974). Plastids. In Algal Physiology and Biochemistry (ed. W. D. P. Stewart), pp. 124-160. Oxford University Press. CATTOLICCO, R. A. (1978). Variation in plastid number: effect on chloroplast and nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid complement in the unicellular alga Olisthodiscus luteus. PL Physiol. 62, 558-562. CHAPMAN, D. J. & HAXO, F. T. (1966). Chloroplast pigments of Chloromonadophyceae. J. Phycol. 2, 89-91. COLEMAN, A. W. (1979). Use of the fluorochrome 4',6-diamidine-2-phenylindole in genetic and developmental studies of chloroplast DNA. J. Cell Biol. 82, 299-305. COWLES, R. P. & BRAMBEL, C. E. (1936). A study of the environmental conditions in a peat bog with special reference to the diurnal vertical distribution of Gonyostomum semen. Biol. Bull. mar. biol. Lab., Woods Hole 71, 286-298. DROUET, F. & COHEN, A. (1935). The morphology of Gonyostomum semen from Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Biol. Bull. mar. biol. Lab., Woods Hole 68, 422-439. ALDRICH, Chlorotnonadophycean chloroplasts 409 S. P. (1970). The comparative ultrastructure of the algal chloroplast. Ann. N.Y. AcadSci. 175, 454-473GIBBS, S. P., CHU, L. L. & MAGNUSSEN, C. (1980). Evidence that Olisthodiscus luteus is a member of the Chrysophyceae. Phycologia 19, 173-177. GUILLARD, R. R. L. (1975). Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. In Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals (ed. W. L. Smith & M. H. Chaney), pp. 29-60. New York: Plenum. GUILLARD, R. R. L. & LORENZEN, C. J. (1972). Yellow-green algae with chlorophyllide c. J. Phycol. 8, 10-14. HERRMAN, R. G. & POSSINGHAM, J. V. (1980). Plastid DNA-the plastome. In Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation (ed. J. Reinert), vol. 10, pp. 45-96. New York: Springer. HEYWOOD, P. (1968). Studies on the Chloromonads. Ph.D. thesis, London University. HEYWOOD, P. (1973). Nutritional studies on the chloromonadophyceae: Vacuolaria virescens and Gonyostomum semen. 3- Physcol. 9, 156-159. HEYWOOD, P. (1977). Chloroplast structure in the Chloromonadophycean alga Vacuolaria virescens. 3- Phycol. 13, 68-72. HEYWOOD, P. (1980). Chloromonads. In Phytoflagellates (ed. E. R. Cox), pp. 351-379. New York: Elsevier/North-Holland. HOVASSE, R. (1945). Contribution a l'etude des Chloromadines: Gonyostomum semen Diesing. Archs zool. exp. gen. 84, 239-269. KOCH, S. & SCHNEPF, E. (1967). Einige elektronemikroskopische Beobachtungen an Vacuolaria virescens Cienk. Arch. Mikrobiol. 57, 196-198. LOEDLICH, A. R. & FINE, K. E. (1977). Marine chloromonads: more widely distributed in neritic environments than previously thought. Proc. biol. Soc. Wash. 90, 388-399. MIGNOT, J. P. (1967). Structure et ultrastructure de quelques Chloromonadines. Protistologia 3. 5-23MIGNOT, J. P. (1976). Complements a l'6tude de Chloromadines. Ultrastructure de Chattonella subsalsa Biecheler flagell6 d'eau saumatre. Protistologica 12, 279-293. POISSON, R. & HOLLANDE, A. (1943). Considerations sur la mitose et les affinities des Chloromonadines. litude de Vacuolaria virescens Cienk. Ann. Sci. not. Zool. (ser. II) 5, 147-160. SHEPARD, D. C. (1970). Photosynthesis in chloroplasts isolated from Acetabularia mediterranea In Biology of Acetabularia (ed. J. Brachet& S. Bonotto), pp. 207. New York: Academic Press. TAYLOR, F. J. R. (1976). Flagellate phylogeny: a study in conflicts..7. Protozool. 23, 28-40. GIBBS, (Received 13 October 1980)