B40.2302 Class #10

advertisement

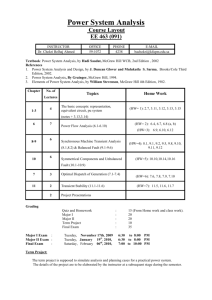

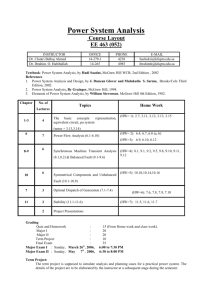

14- 1 B40.2302 Class #10 BM6 chapters 13, 18.4 13: Financing decisions and market efficiency 18.4, non-BM6 material: The effect of asymmetric information non-BM6 material: The effect of market inefficiency Based on slides created by Matthew Will Modified 11/14/2001 by Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Principles of Corporate Finance Brealey and Myers Sixth Edition Corporate Financing and the Six Lessons of Market Efficiency Slides by Matthew Will, Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill Chapter 13 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 3 Topics Covered We Always Come Back to NPV What is an Efficient Market? 3 forms Some supporting evidence Efficient Market Theory Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 4 Return to NPV A basic similarity between investment and financing decisions: Can think about both in NPV terms The decision to purchase a factory (investment decision), or sell a bond (financing decision), each involve valuation of a risky asset Each decision could in principle add value Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 5 Return to NPV Example: the value of a below-market-rate loan As part of a policy of encouraging small business, the government is lending you $100,000 for 10 years at 3%. What is the value of this below-market-rate loan? NPV(loan) amount borrowed - PV of interest - PV of principal Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 6 Return to NPV Example: the value of a below-market-rate loan As part of a policy of encouraging small business, the government is lending you $100,000 for 10 years at 3%. What is the value of this below-market-rate loan? Assume the market return on equivalent-risk projects is 10%. 10 3,000 100,000 NPV(loan) 100,000 t 10 ( 1 . 10 ) ( 1 . 10 ) t 1 100,000 56,988 $43,012 The firm adds over $43,000 in value by accepting the below-market-rate loan. (Thank you Uncle Sam.) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 7 Return to NPV Some differences between investment and financing decisions Number of financing decisions is expanding faster Financing decisions usually easier to reverse Probably easier to add value through investment decisions In investment decisions, firm is competing for NPV>0 investments with other industry competitors In financing decisions, firm is competing for NPV>0 financing opportunities with all firms, governments, investors around the world All of this competition may lead to “efficient markets” in which NPV(financing) = 0 (ignoring tax shields, other financing costs/benefits). Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 8 Return to NPV How does market efficiency affect financing? Think of value of firm as an APV calculation: PV(firm) = PV(investments base-case) + NPV(financing) Under M&M assumption of efficient markets… NPV(financing) = 0 (no “below-market-rate” loans/overpriced stock issues available) (and assuming no tax shields, issue costs, etc. as before) … which leads to M&M conclusion: PV(firm) = PV (investments base-case) while “financing is irrelevant” because it’s NPV=0 Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 9 Return to NPV How does market efficiency affect financing? But in inefficient markets, maybe NPV(financing) >0 Financing may be “relevant” if firm can find ways to finance at “below-market” costs, i.e. ways to finance below its rational cost of capital So market efficiency is central to M&M conclusion Are markets efficient or not? A controversial issue in finance Evidence that markets are approximately efficient However, can find exceptions if one looks carefully at the data These may be important enough to affect financing decisions Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 10 Market Efficiency: 3 versions Weak Form Efficiency Market prices reflect past price information. Prices move as a “random walk” Semi-Strong Form Efficiency Market prices reflect all publicly available information, not just past prices Strong Form Efficiency Market prices reflect all information, both public and private. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 11 Weak Form Efficiency Early discovery: The day-to-day changes in stock prices (or bond prices) DO NOT reflect any strong pattern Instead, prices seem to take a “random walk” up and down Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 12 Weak Form Efficiency In the coin toss game, winnings are a random walk Heads Heads $106.09 $103.00 Tails $100.43 $100.00 Heads Tails $97.50 Tails Irwin/McGraw Hill $100.43 $95.06 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 13 Weak Form Efficiency 5 yrs of S&P 500? or 5 yrs of the coin toss game (with drift)? Level 180 130 80 Month Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 14 Weak Form Efficiency Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 15 Weak Form Efficiency Technical Analysis Idea is to forecast stock prices based on fluctuations in past prices T.A. doesn’t pay if markets are weak form efficient Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 16 Weak Form Efficiency $90 Microsoft Stock Price 70 The idea: 50 Cycles selfdestruct once identified Last Month Irwin/McGraw Hill This Month Next Month ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 17 Semi-Strong Form Efficiency Cumulative Abnormal Return (%) Average “abnormal returns” (returns relative to CAPM benchmark) around the announcement that firm X is a takeover target pattern is consistent with semi-strong efficiency: once news is out, no abnormal returns Irwin/McGraw Hill 39 34 29 24 19 14 9 4 -1 -6 -11 -16 Announcement Date Days Relative to annoncement date ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 18 Semi-Strong Form Efficiency Another situation consistent with semi-strong efficiency: How stock splits affect value 35 30 Cumulative abnormal return % 25 20 15 10 5 0-29 0 30 Month relative to split Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 19 Semi-Strong Form Efficiency Fundamental Analysis Idea is to find undervalued stocks from analysis of the “fundamental value” of cash flows F.A. doesn’t pay if markets are semi-strong efficient Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 20 Semi-Strong Form Efficiency Average Annual Return on 1,493 Mutual Funds and the Market Index, 1962-1992. 40 30 Return (%) 20 10 0 -10 Funds Market -20 -30 Irwin/McGraw Hill 19 92 19 77 19 62 -40 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 21 Strong Form Efficiency • Strong form efficiency says that market prices properly reflect all public and private information • This is an extreme version of efficiency, nobody believes it • Proof that markets do not reflect all private information: -- illegal insider trading is profitable Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 22 Theory of efficient markets When should market efficiency hold? Case 1. All investors are rational • Rational investors value securities for the present value of their future cash flows. • So if P =/= PV(cash flows), they will buy or sell until it does. Case 2. Some investors are irrational, but their misperceptions are uncorrelated • Optimistic and pessimistic investors will “cancel out” Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 23 Theory of efficient markets When should market efficiency hold? Case 3. Many investors may be irrational, but the rational investors offset their effect with arbitrage trades • The most general, most powerful argument • Arbitrage: “the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same, or essentially similar, security in two different markets at advantageously different prices” • For example: If McDonald’s is overpriced, arbitrageurs can short-sell McDonald’s, buy Burger King to hedge their risk, and hold on for a low-risk (hopefully riskless) profit • This forces McDonald’s price back down to the efficient value • Argument is less compelling when there are costs/risks to this sort of arbitrage Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Principles of Corporate Finance Brealey and Myers Sixth Edition How Much Should a Firm Borrow? Slides by Matthew Will, Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill Chapter 18.4 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 25 Topics Covered Pecking Order Theory Theory of financing decisions Theory of capital structure Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 26 Pecking Order Theory Pecking Order Theory of Incremental Financing Decisions - Theory that uses asymmetric information to argue that firms prefer to fund their investments using internal finance, then (if internal finance is insufficient) by debt issues, then (as a last resort) by equity issues. Pecking Order Theory of Capital Structure – Theory in which capital structure evolves as the cumulative outcome of past incremental financing decisions, each of which is taken using the above rule. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 27 Pecking Order Theory Where does the POT of financing decisions come from? Starting point is that managers know more than investors about firm value -- and that investors recognize their disadvantage I.e., there is “asymmetric information” I.e., the market is semi-strong form efficient but not strong-form efficient This seems reasonable … E.g., when a company announces a dividend increase, price goes up This is because investors interpret the increase as a sign of managers’ confidence in future earnings So the dividend increase carries information only if managers do indeed know more in the first place Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 28 Pecking Order Theory How does asymmetric information affect the choice between debt and equity? - Imagine two companies, O and U. To investors, they appear identical. But O’s managers know that O’s stock is Overpriced … And U’s managers know that U’s stock is Underpriced … Both O and U have an investment project and need to raise $. Should they issue equity or debt? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 29 Pecking Order Theory Managers of O are thinking: Our products were popular for a while, but the fad is fading. It is all downhill from here. How are we going to compete with the new entrants? Fortunately our stock price has held up – we’ve had some good short-run news for the press and security analysts. Now’s the time to issue stock. Managers of U are thinking: Sell stock at our current low price? Ridiculous! It’s worth at least twice as much. A stock issue now would hand a free gift to the new investors – the old investors would be selling a big piece of the pie for a small price. I just wish those stupid, skeptical investors would appreciate the true value of this company. Oh well, the decision is obvious: we’ll issue debt, not underpriced equity. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 30 Pecking Order Theory So O wants to issue stock, but U wants to issue debt. Investors (in the pecking order theory) are not stupid – they understand these motives They view stock issues as a sign of overvaluation They view debt issues as a sign of undervalution So O’s stock price will drop if it announces a stock issue, presumably eliminating the overvaluation (semi-strong efficient) In practice, stock prices do fall upon announcement of a new stock issue Thinking this through, even O will prefer debt over stock issues. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 31 Pecking Order Theory Thus, asymmetric information favors debt over equity issues Debt is higher on the “pecking order” than equity In practice, debt issues are more common than equity issues, consistent with the P.O. prediction Internal finance is even better It is highest on the pecking order Investing with internal finance sends no signal about the firm’s true value; it avoids issue costs and information problems completely May therefore be worth accumulating internal finance Thus, ‘pecking order of incremental financing choices’ A theory of day-to-day financing decisions ‘Internal finance preferred to debt issues preferred to equity issues’ Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 32 Pecking Order Theory ‘Pecking order theory of capital structure’ Says that ‘capital structure is just the cumulative outcome of past, pecking-order-driven financing decisions’ No “grand plan” or “optimal” debt-equity ratio Each firm’s debt-equity ratio just reflects its cumulative requirements for external finance Fits empirical fact: Profitable firms have lower D/E ratios P.O. theory is consistent with this fact: more profits more internal finance available don’t need outside money. (Whereas less profitable firms issue and accumulate debt because they don’t have internal funds) Tradeoff theory predicts the opposite: more profits more value to tax shields should have more debt Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Market Inefficiency and Corporate Finance Slides by Jeffrey Wurgler Not in book 14- 34 Topics Covered Evidence of market inefficiency? Market timing theory Theory of financing decisions Theory of capital structure Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 35 Evidence of market inefficiency? Our theoretical arguments for market efficiency are strong, but have some holes In practice, “arbitrage” is usually costly and/or risky It is costly to short-sell overpriced stocks Individual stocks don’t have perfect substitutes; e.g., the “short McDonalds, hedge with long Burger King” trade has risk Real “arbitrageurs” may be capital-constrained: they can’t pursue all the good opportunities (NPV>0 trades) that they perceive And so forth … Bottom line is that theoretical argument for market efficiency is strong, but not overwhelming: There is some evidence of inefficiency when one looks carefully at the data Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 36 Evidence of market inefficiency? Calendar effects [refer to appendix slide 1] January effect: Small stocks do well in January [2] September effect: Stocks in general do badly in September [3] Turn-of-month effect: Stocks do well around the turn of the month Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 37 Evidence of market inefficiency? Firm characteristics effects [4] Size effect: Small-cap stocks do better than large-cap stocks [5] Book-to-market effect: Stocks with high book-to-market equity ratios (“value stocks”) do better than stocks with low ratios (“growth stocks”) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 38 Evidence of market inefficiency? Overreaction to non-news? [6] Is there real information driving all the major market moves? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 39 Evidence of market inefficiency? Underreaction to genuine news? [7] Post-earnings-announcement drift: stocks seem to underreact to earnings announcements [8] Momentum: stocks that have gone up in past 3-12 months keep going up, and vice-versa. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 What should managers do in inefficient markets? 14- 40 Remember the pecking-order logic: In markets that are semistrong but not strong efficient, managers try to avoid issuing equity, since it sends a bad signal, stock price drops instantly But if (as some evidence suggests) markets are not even semi-strong efficient, then investors may underreact to the bad news (overvaluation) inherent in a new stock issue If so, managers may be able to “time the market” – get an overpriced equity issue out without a big price drop Effectively, they can obtain equity at an irrationally low cost This benefits incumbent shareholders at the expense of the new ones Can they do this? Do they? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 41 Market timing Evidence of successful “market timing” – firms seem to issue equity when its price is too high (cost of equity is low), repurchases when price too low (cost of equity is high) [9] IPOs underperform the market index [10] SEOs underperform the market index [11] When aggregate equity issues are high relative to aggregate debt issues, subsequent equity market returns are low [12] Repurchases outperform (beat) the market index Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 42 Market Timing Theory ‘Market timing theory of financing decisions’ Financing theory when markets are not semi-strong efficient, e.g. when investors underreact to the bad news in equity issue or the good news in a repurchase Says raise whatever form of finance is currently available at the lowest risk-adjusted cost. (In M&M efficient markets, this makes no sense, since all forms of finance are efficiently priced at the same risk-adjusted cost.) For example, issue equity if it is relatively overpriced, or long-term debt if it is relatively overpriced, or short-term debt if it is relatively overpriced Consistent with empirical evidence that firms can “time the market” Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 43 Market Timing Theory ‘Market timing theory of capital structure’ Says capital structure is just the cumulative outcome of markettiming-motivated financing decisions No “grand plan” or “optimum” debt/equity ratio Capital structure just the cumulative outcome of past efforts to time the markets Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000