What happens at the shoulder during throwing?

advertisement

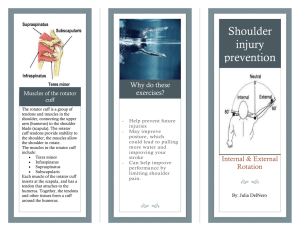

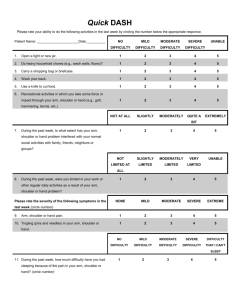

Shoulder Health and Throwing Take a moment and think of the fastest motions that occur in all of sports. There’s kicking a soccer ball with full power, taking a slap shot in ice hockey, or even taking a shot in lacrosse. All of these are no doubt very fast, but they all take a back seat to throwing a baseball. Throwing a baseball is without a doubt the single fastest motion that occurs in ALL of sports. Elite level pitchers are able to produce rotational arm speeds of up to 7,000 degrees per second! But do you know exactly what goes on at your shoulder to produce this type of movement? Before we dive into the details of what’s occurring at your shoulder during the throwing motion, let’s review some basic anatomy. There are three bones that make up your shoulder. Two of these bones, the clavicle and the scapula, make up what’s called your shoulder girdle. Your shoulder girdle connects your upper limb to the rest of your skeleton via the sternoclavicular joint (right below your neck). The third bone, your humerus, interacts with your scapula to form your actual shoulder joint. Here’s a picture to clarify things a little bit. The picture on the left is your right arm viewed from the front. The picture on the right is your right arm viewed from behind. ^ The Lovely Bones (any Mark Wahlberg fans reading this? It wasn’t one of his best films, but Marky Mark is the man and I will not hesitate to use a reference that involves him. Mooooving on…) Now I’m sure everyone is aware that we have muscles that attach to these bones that cause all of our movement. In trying not to turn this article into an excerpt from my college kinesiology text book, I won’t name them all here. But some of the major muscles include the trapezius, rhomboids, deltoids, pectorals, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and the infamous rotator cuff. Here’s a visual. (FYI, the rotator cuff is composed of your supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis (not pictured)) View from the back. So what actually happens at your shoulder when you throw a baseball? Well, a lot really. This isn’t Rookie of the Year where you can just cock back your arm at 90 degrees and throw some serious heat… quite the contrary. Throwing a baseball requires the coordination and synchronized motion of all the joints and muscles previously mentioned, and some that weren’t! When you move your arm, especially during overhead movements, there needs to be appropriate movement of the scapula to allow the humerus to move freely. At various stages during a throw, your scapula may be tilting forward or backward, shifting closer or further away from your spine, or rotating upward or downward. This might not seem like a big deal, but if your scapula doesn’t move adequately, there’s a good chance your arm won’t either. Scapular upward rotation is vital to any overhead athlete. Without proper upward rotation from your scapula, you likely will not be able to raise your arm overhead without compensations from other parts of your body (ex: arching your low back, shooting your head forward). Compensating for this faulty movement pattern can lead to other negative issues in the future such as improper throwing mechanics, or worse, injury. During throwing, the arm needs to move throughout a pretty big range of motion at incredible speeds, especially during acceleration and deceleration. As you can see, there’s overhead motion occurring which is why appropriate movement patterns at the scapula and humerus are necessary to complete a throw. In addition to this, there’s internal and external rotation of the humerus. External rotation occurs during the loading or cocking action of the arm, while internal rotation occurs during the forward motion or acceleration portion of the throw. For this reason, the rotator cuff needs to work very hard throughout this entire motion. First, it needs to stabilize the humeral head within the glenoid fossa (socket). This prevents the humerus from sliding too far forward or up which can lead to issues such as pain. Second, the cuff needs to decelerate the internal rotation of the humerus after the ball is released. This is where injuries to the rotator cuff tend to happen, mainly because the cuff is not strong enough to handle the load of decelerating this rotation. Ideally we’d like to avoid this, so we want to make sure the rotator cuff has ample strength. But if a few things go wrong within this motion, or if compensatory patterns are needed to complete them, injuries can occur. They can be acute, meaning sudden, or they can be chronic, meaning they have gradually built up over time. Regardless, they can definitely be avoided with proper training. One of the most common issues that can arise with regards to shoulder issues is tightness in the surrounding muscles. For example, if the lats, pecs, or upper traps are tight, it can limit the movement of the scapula which in turn will limit total arm range of motion. Since these muscles are used quite a bit during the throwing motions, overworking them in the weight room can lead to more problems (assuming they’re already tight). Another issue could be weakness of the scapular stabilizing muscles. If the scapula is unstable, you’re setting yourself up for less than optimal shoulder movement. Try to remember the phrase “you can’t fire a cannon from a canoe” when thinking of the shoulder. You can’t expect your arm (cannon) to produce tremendous amounts of force when your scapula (canoe) can’t maintain stability. Lack of mobility in the thoracic spine (think middle of your spine, right in between your shoulder blades) will also limit shoulder mobility as the thoracic spine impacts the positioning of your ribcage. Conveniently, the ribcage also happens to interact with and affect scapular positioning. And would you believe me if I told you the positioning of your pelvis affects your shoulder? So when you have one or a combination of these issues, continually performing overhead work on the field or weight room might not be the best option for you. Continually utilizing compensatory movement patterns to achieve full shoulder range of motion is not something you want your athletes to be doing, as there is a good chance injuries may be a result of this. Take some time to fix these issues and avoid any unnecessary trips to the physical therapist, doctor, or disabled list. In a follow up article, I’ll go over some guidelines to follow that ensure the shoulder stays healthy and functioning efficiently. Chris Sanchez, CSCS