The Population Problem: New Debates, New Ideas, and New

advertisement

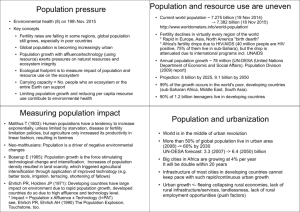

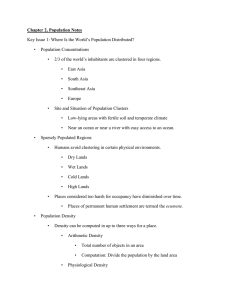

Evidence on how Population and Reproductive Health Impact Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction David Canning Harvard School of Public Health November 2, 2006 Theory and Evidence • Theoretical models tell us what evidence to look for. • There are many mechanisms that potentially link population to growth and poverty reduction. • Evidence of a narrow focus in the past on the effect of population growth rate on economic growth. Theory: Population Effects on economic growth • Malthusian – exhaustible resources (climate) • Neo-classical growth theory – capital dilution • Positive scale effects – technological progress and agglomeration externalities Impact of population growth on economic growth • Use cross-national data. • Standard finding was of little effect of population growth on economics growth (NAS Report 1986). • Result still holds today. The 1986 Report in Historical Context • The report was “revisionist” (Kelley 2001) as opposed to other “population-alarmist” reports. • The authors were economists and allowed for market and institutional mechanisms that may alleviate the negative consequences of population growth. Critiques • We have been looking at the wrong level of aggregation. Many effects may occur only at the global or city level. • Other theoretical models would make us look at different evidence. • Test conflates several different effects. Other Theories • Quality- quantity tradeoff – health and education of children • Maternal health and productivity • Female labor market participation • Transition from family support to saving for old age • Age structure effects – – Labor supply and saving vary with age. • Differential effects of fertility, mortality and migration Components of Population Growth • Population growth can be decomposed into the crude birth rate, minus the crude death rate, plus inward migration. • Looking at effects of population growth as a whole assumes these components have exactly equal effects - the effect of a birth is the same as an inward migrant or a death avoided. • The economic impact of changes the birth rate, death rate, and migration rate are likely to be very different. Mortality and Health • Low death rates are associated with healthier populations; evidence has emerged for such an effect in both the micro and macro literature. • It is common to capture health in growth regressions by life expectancy • This “health productivity” can be separated from the population effect Crude Birth Rate vs. Crude Death Rate, 1800-2000 50 Population grow th rate = 2%/yr Population grow th rate = 1%/yr Population grow th rate = 0%/yr 1950 Crude Birth Rate (per 1,000) 40 30 2000 Sweden 1900 1900 1800 Japan 20 India 10 2000 0 0 10 20 30 40 Crude Death Rate (per 1,000) 50 Demography and Growth • Low birth rate and low death rate are both associated with faster economic growth. • A high (and rising ) ratio of working age to dependent population is associated with economic growth. • The effect is robust in growth models and help forecast economic growth. • Identification – timing. Past demography is uncorrelated with future growth shocks. Age Structure and Accounting • There is an accounting effect of age structure, where we take age specific behavior to be constant and look at the effect of a changing age pattern. • This gives large effects of age structure change on labor supply and saving. • Age structure can be written as a function of past fertility, mortality and migration rates. Total labor force participation rates by age group 90 80 70 Participation rate Bolivia 1996 60 Dominican Rep 1996 50 Ecuador 1995 El Salvador 1995 40 Honduras 1998 Nicaragua 1993 30 Peru 1997 20 10 0 15-18 19-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-45 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 Age cohort 65+ Income and Consumption by Age, Taiwan 1998 500000 400000 300000 200000 100000 0 -100000 0 Income Consumption 20 40 Age 60 80 100 Demography and Saving • Investment rates in most countries are closely tied to domestic savings rates. • Savings rates vary with age. Changing age structure towards the older working age groups (who have high savings rates) tends to increase national savings rates. • Macro effects are larger than those found by calibration based on micro data – perhaps due to the fact that aging populations have longer life expectancy generating higher savings rates for retirement at all ages. Thousands US Foroign Born Population Entered 2000-2003 by Age 1,000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Age 60 70 80 90 East Asia: Age Structure 160 140 120 Population 100 (m illions) 80 2050 60 2025 40 2000 20 0 0-4 1975 1950 10 14 20 24 30 34 40 44 50 54 60 64 Age group 70 74 80 84 90 94 100+ Year Sub-Saharan Africa: Age Structure 180 Population (millions) 160 140 120 100 80 2040 60 2010 40 1980 20 1950 0 0 - 4 10 - 20 - 30 - 40 - 50 - 60 - 70 - 80 - 90 - 100+ 14 24 34 44 54 64 74 84 94 Age group Year Ratio of Working Age to Dependant Population 2.5 2.0 Ratio 1.5 1.0 East Asia USA Sub-Saharan Africa South Asia Europe 0.5 0.0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Year 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Interactions • High rates of growth of the working age population produce an increase in labor supply. • This supply must be met by demand if it is to be employed. • We have evidence that the beneficial effects of age structure change only occur in countries with good institutions and economic policies • Estimation different from calibration Poverty Reduction • Cross country poverty and inequality data is very low quality. • Little evidence of an effect of fertility on inequality in macro data (poor get proportional benefits). • Some evidence that demographic transition occurs first among the better off, widening income inequality. • The poorer families “catch up” later in the transition. Economic Growth, Welfare, and Population Policy • We find that lower fertility promotes growth in GDP per capita. However, GDP per capita is not a welfare measure. A broader notion of welfare is required. • If the benefits and costs of fertility fall entirely on the family, we should aim to achieve desired fertility. We do not have evidence here of externalities (need to compare effect within and across families). Poverty Trap • The temporary boost in GDP per capita due to the demographic transition may help countries escape from a poverty trap. • The feedbacks from income, health and education to fertility are a technical problem for identifying the direction of causality. • They are conceptually important in understanding the process of development since they set up a self reinforcing, positive feedback, system • Points to research on determinants of desired fertility, and the system, as well as the consequences of filling unmet need. Casual Effects in Microdata • Determining the effects of mortality, fertility, and migration pose quite different problems • Desired fertility is a choice and is the product of a joint decision. • Random shocks (unplanned births, infertility) identify the effect of fertility on behavior. • Access to family planning for unmet need is a good instrument as it is also the likely policy intervention. • Changing desired fertility is likely to have different effect from providing services to reduce unmet need. Micro Evidence • Large family size is associated with poverty. • Few studies try to get at causality • Twins and sex composition (with male preference) are not good instruments. Microeconomic evidence: the economic effects of lowering fertility – determining causality • Miller, 2005, quasi-random placement of family planning services in Columbia, effects of women’s education and labor supply. • Joshi and Schultz, 2006, MATLAB family planning experiment in Bangladesh, effect on child health, woman’s health, and income. Focus: Theory • Which mechanism (theoretical effect) is to be focused on? • Can we determine causality rater than association.