Implementing and Evaluating a Program of Patient Safety

advertisement

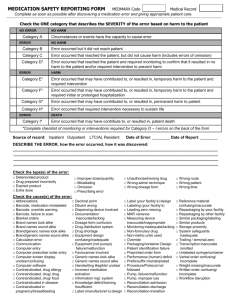

Implementing and Evaluating a Program of Patient Safety Successful Reporting Systems as the Foundation Katherine Jones, PhD, PT Anne Skinner, RHIA Gary Cochran, PharmD Keith Mueller, PhD Supported by AHRQ Grant 1 U18 HS015822 Objectives Explain the role of voluntary reporting systems in a program of patient safety Identify the characteristics of successful reporting systems Identify information necessary for systematic data collection in a medication error reporting program Understand how the NCC MERP Taxonomy of error severity provides a language to describe errors in the context of a system 2 The Problem… “The problem is not bad people; the problem is that the system needs to be made safer . . . Voluntary reporting systems are an important part of an overall program for improving patient safety and . . . have a very important role to play in enhancing an understanding of the factors that contribute to errors.” To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System 3 Reporting is the foundation of a culture of safety “Any safety information system depends crucially on the willing participation of the workforce, the people in direct contact with the hazards. To achieve this, it is necessary to engineer a reporting culture—an organization in which people are prepared to report their errors and near-misses.” 4 Components of Safety Culture INFORMED = SAFE A culture of safety is informed. It never forgets to be afraid… LEARNING FLEXIBLE JUST REPORTING Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 1997. 5 Reporting is supported by just, flexible, and learning cultures The willingness of workers to report depends on their belief that management will support and reward reporting and that discipline occurs based on risk-taking…there is a clear line between acceptable and unacceptable behavior workers—organizational practices support a just culture. The willingness of workers to report depends on their belief that authority patterns relax when safety information is exchanged because managers respect the knowledge of front-line workers—organizational practices support a flexible culture. 6 Reporting is supported by just, flexible, and learning cultures Ultimately, the willingness of workers to report depends on their belief that the organization will analyze reported information and then implement appropriate change— organizational practices support a learning culture. The interaction of practices that support reporting, just, flexible, and learning cultures produces an informed, safe organization that is highly reliable. The organizational beliefs and practices associated with these components of culture are assessed by the AHRQ HSOPSC. 7 Characteristics of Successful Reporting Systems Nonpunitive: reporters do not fear punishment as a result of reporting Confidential: identities of reporter, patient, institution are never revealed to a 3rd party Independent: reporting is independent of any authority who has the power to discipline the reporter Expert analysis: reports are analyzed by those who have the knowledge to recognize underlying system causes of error Timely: reports are analyzed promptly and recommendations disseminated rapidly Systems-oriented: recommendations focus on systems not individuals Responsive: those receiving reports are capable of disseminating recommendations Leape, LL. (2002). Reporting of adverse events. NEJM, 347, p. 1636. 8 MEDMARX® MEDMARX is an anonymous medication error reporting program that subscribing hospitals and health systems participate in as part of their ongoing quality improvement initiatives. Nationally, data from MEDMARX contributes to knowledge about the causes and prevention of medication errors. Over 870 hospitals and health systems have submitted more than 1.3 million medication error records to MEDMARX. Analyses of voluntary medication error reports from large patient safety databases, such as MEDMARX, can identify system sources of error and lead to the establishment of safe medication practices. Stevenson JG. Medication errors: Experience of the United States Pharmacopeia. Jt Comm J Qual Safe 2005;31(2):106-111. 9 www.MEDMARX.com 10 Systematic Data Collection in Medication Error Reporting Error severity based on the outcome to patient Description of the error Phase of the medication use process in which the error originates Type of the error Cause of the error Contributing factors to the error Information about the drug(s) involved 11 NCC MERP Taxonomy of Error Severity A: capacity to cause error B: error occurred, did not reach patient C: error reached patient, no harm D: error reached patient, monitoring and intervention required E: temporary harm requiring intervention F: temporary harm requiring initial or prolonged hospitalization G: permanent harm H: intervention required to sustain life I: error contributed to or resulted in death http://www.nccmerp.org/pdf/taxo2001-07-31.pdf 12 13 Reporting Error Severity Error Severity Jan - June 2007 (31 CAHs submitted 2,799 reports) D (reaches pt, monitoring) 2% E (temporary harm) 0% F (harm, hospitalization) 0% A (potential error) 28% C (reaches pt, no harm) 50% B (near-miss) 20% 14 Reporting Where Errors Originate Phase of Error Origination Jan - June 2007 (31 CAHs submitted 2,799 reports) Monitoring 0% Procurement 1% Prescribing 5% Documenting 26% Administering 58% Dispensing 10% 15 Reporting Types of Errors Jones et al. (2006). http://www.unmc. edu/rural/documents/p r06-08.pdf 16 17 Similar products Dosage form confusion Knowledge deficit Dispensing device 2006 (35 CAHs, 4,197 reports) Reconciliation admission MAR variance Written order Drug distribution system 2005 (25 CAHs, 3,897 reports) Computer entry Workflow disruption Communication Documentation Transcription inaccurate/omitted Performance/human deficit Procedure/protocol not followed Reporting Causes Causes of Errors Errors (B -I) Jan 2005 - June 2007 2007 (31 CAHs 2,799 reports) 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Reporting Contributing Factors Contributing Factors to Errors (B -I) Jan 2005 - June 2007 2005 (25 CAHs, 3,897 reports) 2006 (35 CAHs, 4,197 reports) 2007 (31 CAHs 2,799 reports) 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% Range orders Staff agency, temporary Emergency situation Patient transfer Shift change None No 24 hour pharmacy Staff inexperienced Workload increase Distractions 0% Staffing insufficient 5% 18 What we heard about using MEDMARX as the foundation for reporting in Critical Access Hospitals: “Before the project, we just counted errors. We never went past the type of error.” “Using MEDMARX increased reporting because people had more knowledge that what we are doing is intended to make the system safer.” “Using the lingo of MEDMARX, errors got broken down into categories that even the board could understand so they were more open to thinking about allocating money for an automated dispensing system.” 19 What we heard continued… “Without the language of errors associated with MEDMARX, all we could talk about was who did it and not what happened and why. MEDMARX created a standardized process that allowed us to collect more information. The use of MEDMARX and its graphs and charts contributes to the perception of errors as having a system source.” “Because we were able to visualize the system through the graphs and charts, we could communicate to staff and take action.” 20