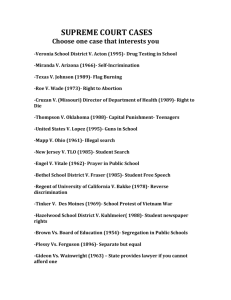

Bakke v. Regents of the University of California

AP Government

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

(1978)

In the 1978 case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the

U.S. Supreme Court ruled that using racial quotas in college admission decisions violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Equal

Protection Clause, included in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution, affirms that "no state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." While this landmark decision eliminated racial quotas, it did allow race to be considered as one of many admission factors for the purpose of achieving a diverse student body.

In a direct challenge to the Bakke decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in the 1996 Hopwood v. Texas case that race could not be a factor in admission decisions. The defendant, the state of Texas, appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, but the appeal was refused. Similarly, in the 2001 Johnson v. University of Georgia case, the U.S. Court of Appeals held that the university's admission policy, which used race as a factor in admission decisions, violated the

Equal Protection Clause. The court ruled that adding a fixed number of points to the admission score of every non-white applicant is not an appropriate mechanism for achieving diversity.

In 1995 and 1996, two lawsuits challenged the constitutionality of using race in the admission processes at the University of Michigan and the University of Michigan Law School. In 1995, Jennifer Gratz was denied admission to the University of Michigan undergraduate program, and a year later Barbara Grutter was rejected from the

University of Michigan Law School. Both plaintiffs argued that their academic credentials and extracurricular activities should have awarded them a spot at the University. They claimed they were subjected to a form of reverse discrimination due to the university's affirmative action policies. The University of Michigan argued that its admission criteria were constitutional, and that the policies fostered a racially and ethnically diverse student body.

1

AP Government

In 2003, the U.S. Supreme Courtruled in the Gratz v. Bollinger case that the point system used by the University of Michigan for undergraduate admissions was unconstitutional. The admissions policy was based on 150 points, and it awarded points based on items such as race (20 points), athletic ability (20 points), depth of essay (up to 3 points), leadership and service (up to 5 points) and personal achievement (up to 5 points). The point system, therefore, automatically awarded admission points to underrepresented minorities. In the majority decision, Chief Justice Rehnquist stated that the University of Michigan had violated the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by using an overly mechanized system as a way to include race in admission decisions.

The Grutter v. Bollinger case of was also decided in 2003. In a 5-4 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly upheld the decision to allow colleges and universities to use race as a component in their admissions policies by ruling in favor of the University of Michigan’s law school admissions policy. Sandra Day O'Connor stated that the

Constitution "does not prohibit the law school's narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body."

The Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger rulings are regarded as the most important since the Bakke decision. Most colleges and universities had previously followed the guidelines set forth by Bakke, stating that diversity is an integral component to a successful institution. They treaded lightly, however, unsure of how far race could be used in the admission's process. The Supreme Court's decisions in the landmark University of Michigan cases clarified this gray area and provided definitive guidance for affirmative action policies. The 2003 rulings also abrogated the Hopwood v. Texas ruling, thus permitting colleges in Texas and other states under the

Fifth Circuit jurisdiction to reinstate affirmative action policies.

2

AP Government

BAKKE SUMMARY

In 1978, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its anticipated decision in the case of the University of

California Regents v. Allan Bakke. There were several cases dealing with the issue of race and education which preceded this case, Bakke was the first in which the judicial system was asked to resolve the issue of affirmative action. The decision handed out by the high court was unsettled and, although temporarily solved that particular case, did very little to resolve the problem or set an order for future cases dealing with the same difficult issue. That decision helped create the current situation and the debate over affirmative action.

The previous case dealing with the racial issue in schools was

Brown v. Board of Education. In 1954, the Supreme Court delivered it's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, declaring segregation illegal and overturning the idea of separate but equal . Allan Bakke was twice denied admission to medical school at the University of California,

Davis. He sued because he said he was a victim of reverse discrimination. Four justices found for the defendant and four for the plaintiff, with Justice Powell split. Because of this unusual split decision, Allan Bakke was admitted to the medical school, but affirmative action was upheld.

Their special admissions program worked by reserving sixteen percent of the entering class for minorities. The minorities entering through this special admissions program were processed and interviewed separately from the regular applicants. The grade point averages and standardized test scores from the special-admissions entrants were significantly lower than the grade point averages and standardized test scores of the regular entrants.

3

AP Government

In 1973, Allan Bakke applied to the medical school at the

University of California. His application was rejected because it was turned in near the end of the year and by the time his application was up for consideration they were only accepting those who had scored 470 or better on their interview scores.

Bakke scored a 468 out of the possible 500. When he learned that four of the special-admissions spots were left unfilled at the time his application was rejected he wrote a letter to Dr.

George H. Lowrey, the associate dean and chairman of the admissions committee, stating how the special admissions system was unjust and prejudiced. When Bakke applied again in 1974, he was again rejected. This time Bakke sued the

University of California.

The Court ruled 5 to 4 in favor of Bakke, striking down U.C.

Davis's explicit set-aside position reserved for minority applicants as unconstitutional. The Court based its decision on its interpretation of individual rights as guaranteed by the 14th

Amendment, which forbids the government from depriving any citizen of due process and equal protection of the laws. As a result of the Supreme Court decision, Bakke was admitted to the medical school and g graduated in 1992. This

Court decision put an end to racial quotas in the admissions process at public universities. The Court did not say that public institutions had to disregard race and ethnicity completely. Instead it stated that race could be considered as long as other factors such as economic disadvantage were considered as well. Thus, the Bakke decision paved the way for the Court and society to continue some affirmative action policies while beginning a discussion of how to better create more diverse representation in university admissions and other aspects of American life.

4

AP Government

The Regents of the University of California v. Bakke was the first Supreme Court decision that directly addressed affirmative action. Because of the split decision, the legal precedent was weak. The Court let existing programs stand. In

1979, it approved the use of quotas in a case of voluntary affirmative action programs in unions and private businesses.

In three cases in 1989, the Supreme Court undercut courtapproved affirmative action plans by giving greater standing to claims of reverse discrimination, voiding the use of minority set-asides where past discrimination against minority contractors was unproved, and restricting the use of statistics to prove discrimination on the grounds that statistics alone do not prove an intent to discriminate.

By the late 1990s, California, and ten other states, banned the use of race- and sex-based preferences in state and local programs. Rather than race or sex, factors as broad as language spoken at home, income level, and parents’ education level are now used to create diversity in schools and the workplace.

5