Norkhalid bin Salimin and Julismah Jani

advertisement

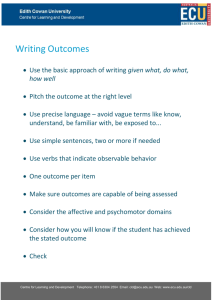

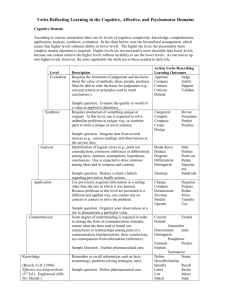

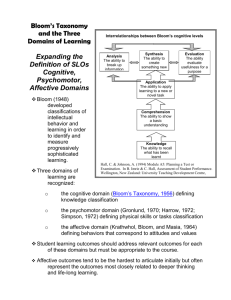

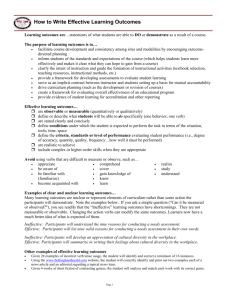

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT FOR BADMINTON IN PHYSICAL EDUCATION Norkhalid bin Salimin¹ and Julismah Jani² ¹Pendidikan Guru, Kampus Ipoh, Malaysia (alittsalimin@yahoo.com) ²Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia (julismah@fsskj.upsi.edu.my) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to identify the extent of student learning outcome within the cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains through the use of the Comprehensive Assessment (CA) for badminton in Physical Education. The study is based on a pre-experimental – the one shot case study design. The study was conducted in secondary schools in the district of Larut, Matang and Selama in Perak. Samplings taken consisted of 15 teachers and 444 Form 2 students in Physical Education classes. The instruments used in the study comprised an assessment scoring rubric in the cognitive domain (r=.75), psychomotor domain (r=.81) and affective domain (r=.81), and teacher agreement questionnaire on the use of CA for badminton (r=.92), with inter-observer agreement percentage for badminton of 70.03% (SD=0.68). The findings showed that the level of students' cognitive achievement (N=432, M=30.35, 75.87%) was good. The learning outcome from psychomotor assessment during training showed hierarchical at manipulation (N=441, M=2.17), and during game sessions was at articulation (N=444, M=3.75). The learning outcome from affective assessment showed hierarchical at characterize (N=444, M=4.29). The study also found that 90.53% of teachers agreed that the use of CA helps to increase the academic performance of students, 88.00% of teachers agreed that it aids in teaching, 95.94% of teachers agreed that the assessment helps to achieve teaching objectives, 79.46% of teachers agreed that the CA meets the features of an assessment, and 58.67% of teachers agreed that the CA is easy to implement. Based on the findings, the CA is suitable as a standard tool for assessing students’ achievement in badminton in the subject of Physical Education. KEYWORDS Comprehensive Assessment, Cognitive, Psychomotor, Affective, hierarchical learning outcome INTRODUCTION Physical Education (PE) is a core and compulsory subject taught under the Integrated Curriculum for Secondary Schools based on the Education Act through Professional Circular No 25/1998 (Ministry of Education of Malaysia, 1998). PE plays an important role in the growth and overall development of students through the learning outcomes in cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains (Darst & Pangrazi, 2006). This study introduces a Comprehensive Assessment (CA) to assess the students' hierarchical in badminton. The CA is developed based on the taxonomies of learning by Bloom et al. (1956) for the cognitive domain, Dave (1970) for the psychomotor domain and Krathwohl et al. (1964) for the affective domain (Figure 1). 1 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Figure 1. Comprehensive Assessment Based on Learning Taxonomies In Malaysia, a formal summative assessment of the PE subject was introduced for the first time (Ministry of Education of Malaysia, 1988) and the assessment comprises two parts, namely examination and national physical fitness standard test (SEGAK) in accordance with Professional Circular No 4/2008 (Ministry of Education of Malaysia, 2008). However, this assessment is not comprehensive enough as students are evaluated only by means of an examination (cognitive) and the SEGAK test (psychomotor) focuses only on the aspect of physical fitness. As such, the existing assessment method for PE subjects is neither complete and holistic nor balanced and comprehensive owing to the unavailability of a standard instrument for use by teachers to assess students, particularly those involving skills in sports (Abdul Manan & Jumalanizon, 2009). OBJECTIVES a. To identify the cognitive, psychomotor and affective students' hierarchical learning outcome based on the Comprehensive Assessment for badminton. b. To identify the extent of teachers’ approval of the use of the Comprehensive Assessment instrument for badminton in Physical Education. METHODOLOGY The study is based on a pre-experimental – the one shot case study design. The study was conducted in secondary schools in the district of Larut, Matang and Selama in Perak. The samples comprised 15 PE teachers and 444 Form 2 students who attended PE classes for badminton. The selection of subject teachers was done using the purposive sampling method, whereas the students were selected intact whereby the teachers would pick a Form 2 PE class and all the students in that class would automatically be used as subjects for the study. The research instrument used was by means of an assessment using a scoring rubric based on the learning hierarchical in the cognitive (r=.75), psychomotor (r=.81) and affective (r=.81) domains. The questionnaire on teacher agreement on the use of CA for badminton was (r=.92) while the percentage of inter-observer agreement for badminton was 70.03% (SD=0.68). The assessment on cognitive learning for badminton consisted of 40 questions arranged according to taxonomic, namely 10 questions on knowledge (25%), 4 questions on 2 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia comprehension (10%), 14 questions on application (35%), 8 questions on analysis (20 %), 2 questions on synthesis (5%) and 2 questions on evaluation (5%). This assessment was based on Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) using the written test method and cognitive achievement rating scale as shown in Table 1. TABLE 1. Cognitive Assessment Rating Scale for Badminton Scale 80 and above 60 to 79 40 to 59 20 to 39 19 and below Rating Excellent Good Satisfactory Fair Poor The psychomotor learning assessment for badminton was divided into 15 sub-skills during training and game sessions. The training session skills included high serves, low serves, backhand serves, forehand stroke, backhand stroke, lob stroke, smashes, basic footwork, backward footwork, forward footwork, and side footwork. While the game session skills included serves, strokes, smashes, and foot works. This assessment was based on Dave’s taxonomy (1970) through the teacher observation method using the rating scale with the rubric classification as shown in Table 2. The affective learning assessment for badminton involved sportsmanship comprising two sub-values, namely accept defeat and respect for opponents. The teacher observation method based on the taxonomy of Krathwohl et al. (1964) was used with scoring rubric as shown in Table 2. TABLE 2. Psychomotor and Affective Assessment Scoring Rubric for Badminton Hierarchical Scale 5 Naturalization 4 Articulation 3 Develop Precision 2 Manipulation 1 Imitation Psychomotor Assessment Evaluation Criteria Unconscious mastery and related basic skills Adapt and integrate basic skill Develop precision basic skill Manipulation basic skill Imitation basic skill Adapt and integrate basic skill Develop precision basic skill Manipulation basic skill Imitation basic skill Develop precision basic skill Manipulation basic skill Imitation basic skill Manipulation basic skill Imitation basic skill Imitation basic skill Affective Assessment hierarchical Scale Evaluation Criteria Adopt belief value system Organize value system 5 Attach values Characterize Participate with value Receive value 4 Organize 3 Value 2 Respond 1 Receive Organize value system Attach values Participate with value Receive value Attach values Participate with value Receive value Participate with value Receive value Receive value The duration of this study comprised four teaching sessions involving two periods (80 minutes) in one school semester. The cognitive assessment consisted of four sets of tests carried out in four teaching sessions. The psychomotor assessment was divided into two 3 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia sessions, namely training and game sessions, while affective assessment was conducted throughout the teaching process. A teacher agreement questionnaire on the use of the CA for badminton was distributed to 15 PE teachers upon completion of the teaching process on badminton skills. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION TABLE 3. Achievement Levels of Learning using Comprehensive Assessment for Badminton Domains N M SD % Achievement Level Cognitive Psychomotor 432 30.35 5.20 75.87 Good Training Session 441 2.17 0.40 72.33 Good Game Session 444 3.75 0.82 75.00 Good 444 4.29 0.70 85.80 Excellent Affective The study showed that the use of CA can help teachers identify the level of achievement based on cognitive, psychomotor and affective domain in teaching and learning. CA became an instrument of assessment to help teachers assess student performance, identify weaknesses, achieve the goals and objectives and assist in teaching and learning process. This study also found out that by using CA, teachers can facilitate the process of student assessment and it is user friendly, time-saving, while the rubric complies with the scoring and the procedure is easy to follow. The results coincided with the assessment criteria of Ryan & Miyasaka (1995) in that the assessment should be designed based on the actual situation and according to the students’ ability, thus encouraging the students to be more interested, motivated, to strive harder and improve on their achievements. TABLE 4. Results Based on Highest Level of Taxonomies using Comprehensive Assessment for Badminton Domains Skills Cognitive Psychomotor Affective N % Achievement Level of Taxonomy 437 88.45 Evaluation Serves Stroke Smashes Foot Works 285 271 209 241 Training Session 64.30 61.30 47.30 54.30 Precision Precision Manipulation Precision Serves Stroke Smashes Foot Works 170 203 195 216 Game Session 38.30 45.70 43.90 48.60 Articulation Articulation Precision Precision 215 48.40 Organize Based on the finding, the CA was related with Fitts and Posner (1967) in the three-stage model of skill acquisition (cognitive stage, associative stage and autonomous stage), which suggested that the novice individual uses the cognitive processes in the early stages of 4 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia learning. In this study, students' cognitive learning achievement was at an evaluation hierarchical level. While students' psychomotor learning achievement on training session was at precision and on game session was at articulation and precision hierarchical level, the results showed that individual differences influenced the level of student achievement on learning skills in PE, in line with the Arnold Gesell theoretical developments (Sultan Idris Teachers' Institute, 1994). In relation to affective domains, students' learning achievement was at organize hierarchical level. This shows that students' create value system in sportsmanship during the PE lesson. Brett & James (2006) stated that the teacher decides which affective behaviors he/she wants students to exhibit and learn. Ladda et al. (1999) suggested that the following 17 behaviors be taught and assessed: 1) altruism, 2) communication, 3) risk-taking, 4) respect, 5) cooperation, 6) effort, 7) followership, 8) goal setting, 9) honesty, 10) initiative, 11) leadership, 12) participation, 13) reflection, 14) commitment-contract, 15) compassion-sympathy, 16) safety, and 17) trust. Most educators often ignore the affective domain owing to the difficulty in making an assessment (McLeod, 1991). However, studies showed that students tend to be more appreciative of teaching strategies that emphasize affective learning outcomes (McTeer & Blanton, 1978). The researcher also analyzed the level of agreement of teachers on the use of the CA instrument in terms of five aspects. The result analysis in Table 5 showed that 90.53% of teachers agreed that CA is able to improve student performance and that students are more attentive and motivated. The findings also showed that 88.00% of teachers agreed that the use of CA can help teachers assess student performance and identify weaknesses, assist in teaching and learning as well as facilitate the management of teaching. About 95.94% of teachers agreed that the use of CA helps achieve the goals and objectives of PE and that it provides simple, clear and appropriate scoring criteria according to the topic in accordance with the learning outcomes. A total of 79.46% of teachers agreed that the use of CA is able to facilitate the process of student assessment, is user friendly, time-saving, while the rubric complies with the evaluation scoring and the procedure is easy to follow. From the aspect of accountability, 58.67% of teachers agreed that the cognitive, affective and psychomotor assessments can be easily implemented, the contents not too heavy, and teaching time will not restrict the assessment process. TABLE 5. Teacher Agreement on the Use of Comprehensive Assessment Agreement Scale Item f Agree Quite Agree Improves student performance 74 90.53% 9.46% Aids in teaching 75 88.00% 4.00% Attains teaching objectives 74 95.94% 2.70% Conforms with the features of an assessment 73 79.46% 15.09% Accountability aspects 75 58.67% 22.67% Disagree 8.00% 1.35% 2.74% 18.67% The results of this study coincided with the assessment criteria of Ryan & Miyasaka (1995) in that the assessment should be designed based on the actual situation and according to the students’ ability, thus encouraging the students to be more interested, motivated, to strive harder and improve on their achievements. In addition, the finding also showed that the problem of the lack of students’ interest in PE (School Inspectorate and Quality Assurance, 5 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia 2009) can be resolved. Accordingly, the CA can provide a systematic way to assess the thinking and reasoning skills of students and assess the results which cannot otherwise be measured through objective tests and essays (Bhasah, 2007). Thus, the CA can help teachers assess and identify students' strengths and weaknesses as well as explain students’ efficiency in performing a skill or activity. The features of the CA are based on performance, greater focus, complex skills, application of specific strategies, problem solving, individual-based, freedom to choose and standards (Marzano et al. 1993). The contents of the evaluation items in the CA are in line with the goals and objectives outlined in the Form 2 syllabus for PE. The scoring criterion was simple and consistent with the taxonomies of Bloom (1956), Dave (1970) and Krathwohl (1964). The scoring rubric used in this study can be used as an evaluation reference based on skills and checklist for describing the performance of each level and as a guide or format (Bhasah, 2007). The construction of the scoring rubric contains features as outlined by Popham (1997), namely selection criteria, quality description and scoring strategy, as well as specific descriptions on what needs to be measured. Thus, the CA is considered user-friendly, facilitates the teachers and has an implementation procedure that is easy to follow. CONCLUSION Based on the results of the study, the Comprehensive Assessment (CA) is suitable for teachers as a standard tool for assessing student performance in the PE subject of badminton. The use of CA is more realistic, holistic and able to assess students in a comprehensive manner in terms of cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains in line with the National Philosophy of Education. The CA is also compatible with school-based assessment and its use indicates the power of knowledge and restores the status quo of PE subjects in schools throughout Malaysia. REFERENCES Abdul Manan Yahi & Jumalanizon Mohamad Rasid (2009). Personal communication. 30 July. Bhasah Abu Bakar (2007). Testing, measurement and evaluation educational. Kuala Lumpur: Prospecta Printers Sdn. Bhd. Bloom, B.S., Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives the classification of educational goals handbook I: cognitive domain.New York: David McKay Company, Inc. Brett, J.H. & James, C.H. (2006). Teaching in the affective domain. Strategies, Sept/Oct 2006, 20, 1113. Darst, P. W. & Pangrazi, R. P. (2006). Dynamic Physical Education for Secondary School Student 5th ed. Massachusetts : Allyn & Bacon. Dave, RH. (1970). Psychomotor levels developing and writing behavioral objectives. Tuscon, Educational Innovators Press. AZ: Fitts, P.M., & Posner, M.I. (1967). Human performance. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole. 6 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., & Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives the classification of educational goals, handbook II: affective domain. New York: David McKay Ladda, S., Demas, K., & Adams, D. (1999). Standard-based, affective assessment for a project adventure unit. Teaching Elementary Physical Education, 10, 18-21. Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D., & McTighe, J. (1993). Assessing student outcomes. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. McLeod, S. H. (1991). The affective domain and the writing process: Working definitions. JAC, 11(1). McTeer, J. H,&Blanton, F. L. (1978). Comparing views of students, parents, teachers, and administrators on objectives for the secondary school. Education, 96, 259–263. Ministry of Education of Malaysia. (1988). Education act through professional circular No 17/1988: syllabus and allocation of time for subjects ICSS. Kuala Lumpur: School Department. Ministry of Education of Malaysia. (1998). Education Act through Professional Circular No 25/1998. Kuala Lumpur: School Department. Ministry of Education of Malaysia. (2008). Education act through professional circular No 4/2008: examination and national physical fitness standard test (SEGAK). Kuala Lumpur: School Department. Popham, W. J. (1997). What’s wrong and what’s right with rubrics. Educational Leadership, 55(2), 72-75. Ryan, J. M., & Miyasaka, J. R. (1995). Current practice in testing and measurement: What is driving the changes? NASSP Bulletin, 79(537), 1-10. School Inspectorate and Quality Assurance (2009). Annual Report in meeting department heads of physical education IPG Malaysia.Mac 2009. Kuala Lumpur. Sultan Idris Teachers’ Institute, (1994). Theories of teaching and the implications. Kuala Lumpur: Academe Art & Printing . 7