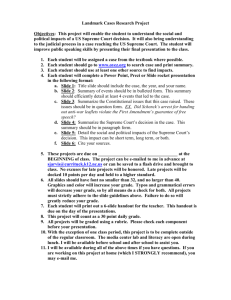

The US Supreme Court and 21st Century Freedom

advertisement

The U.S. Supreme Court & 21st Century Freedom Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University New Ideas in History Conference October 22, 2007 The U.S. Supreme Court & 21st Century Freedom • We will review the 2006-2007 Term of the Court via statistics and some controversial decisions. • We will then look ahead to the current Term and see what issues the Court will be deciding in the coming months. • Throughout, I will suggest that Justice Anthony Kennedy is perhaps the most powerful person and the Supreme Court is the most dangerous branch in America. Number of Dissenting Votes: 2006-2007 Term 30 25 20 15 10 5 Th om as Sc al ia Al ito St ev en s G in sb ur g Br ey er So ut er Ke nn ed y Ro be rts 0 The Court’s four liberals dissent most often. Kennedy followed by Roberts and Alito are less extreme than their colleagues. Percent in Majority in 5-4 Decisions: 2006-2007 Term Th om as Sc al ia Ro be rts Al ito Br ey er Ke nn ed y So ut er St ev en s G in sb er g 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Justice Anthony Kennedy is the decider, regardless of whether the majority includes Conservatives or liberals. 5-4 Decisions: 1995-2006 Terms 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 20 06 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 98 19 97 19 96 19 95 0 The Court has never been more divided in terms of 5-4 decisions. It’s Justice Kennedy’s World and You Just Live in It • Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was often considered the “swing vote” during her tenure (1981-2005). But she was only in 5-4 majorities about 2/3 of the time. • Kennedy had been in 5-4 majorities ½ to 2/3 of the time. • Now Kennedy is in all of them. • Let’s look at some issues from the last Term and the current one to see how Kennedy makes the difference. Gonzales v. Carhart (2007) • • • • • In Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), the Court struck down, 5-4, a state law that banned, so-called “partial-birth” abortion—a specific method of late-term abortion where part of the fetus enters the birth canal before it is aborted. Doctors testified that they only used this procedure when it ensures the health and safety of the woman. Justice O’Connor agreed and struck down the ban as Roe v. Wade (1973) requires exceptions for maternal health. The federal Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 also banned the procedure. But unlike the Nebraska statute, the legislation included lengthy sections explaining how the procedure was unnecessary for maternal health. By a vote of 5-4 the Court upheld the law—the first time the justices upheld a prohibition on a specific method of abortion. Justice Kennedy wrote the opinion, deferring to the congressional findings on the procedure. O’Connor’s replacement, Justice Alito, voted to uphold the ban demonstrating how judicial appointments can have an important effect on judicial policymaking. President George W. Bush and Judge Samuel Alito Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007) • • • • • By a vote of 5-4 the Court struck down voluntary school integration plans which use a student’s race to govern the availability of a place at a desired school, even for the purpose of preventing resegregation. Chief Justice Roberts said that while governments may take race into account under certain circumstances, such as making up for specific past discrimination and as one of many factors to achieve diversity, race cannot be determinative as it was in this case: “under each plan when race comes into play, it is decisive by itself.” Justice Kennedy, a member of the conservative majority, refused to sign the more far-reaching parts of the chief justice’s opinion that he felt would have barred even more general considerations of race. Reading his dissent from the bench, Justice Breyer remarked on the Court’s shift to the right with the appointments of Roberts and Alito: “It is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much.” Alito voted to invalidate the schemes, while it is likely that O’Connor would have upheld them. Chief Justice John Roberts Panetti v. Quarterman (2007) • In a 5-4 decision the Court held that a mentally ill convicted murderer who was delusional and lacked a “rational understanding” of why the state had sentenced him to death could not be executed. Therefore capital defendants can challenge their sentences on mental illness grounds at any point prior to their execution. • Kennedy wrote the opinion and joined the four liberals in yet another example of his skepticism about the reach of the death penalty. • This coalition also struck down the death penalty for juveniles and the mentally ill in two previous cases. Justice Anthony Kennedy 2007-2008 Term: Baze v. Rees • • • • • • Do death sentences carried out by lethal injection violate the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment? The Kentucky Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of lethal injection last year, noting that of the 38 states that permit capital punishment, the majority use the injection method because it is "universally recognized as the most human method of execution and the least apt to cause unnecessary pain." The lethal injection method calls for the administration of four drugs: Valium, which relaxes the convict, Sodium Pentathol, which knocks the convict unconscious, Pavulon, which stops breathing, and potassium chloride, which essentially puts the convict into cardiac arrest, ultimately causing death. Two inmates are challenging Kentucky's four-drug lethal injection protocol. The Kentucky Supreme Court noted that only one person has been put to death under the state's lethal injection method. It observed that the convict went to sleep within a minute of the first injection and did not move or show any evidence of suffering during the remainder of the process. The Court has been issuing stays on pending executions since it granted the case on September 25, 2007. Therefore, states that use the lethal injection method will have to wait until the Court’s decision is announced sometime before July 2008. • • • • • • In 2006, 53 persons in 14 States were executed -- 24 in Texas; 5 in Ohio; 4 each in Florida, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Virginia; and 1 each in Indiana, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, California, Montana, and Nevada. Of persons executed in 2006, 32 were white and 21 were black. All 53 inmates executed in 2006 were men. Lethal injection accounted for 52 of the executions and electrocution for one. Currently lethal injection is the method used or allowed in 37 of the 38 states which have the death penalty. Nebraska requires electrocution. Other states also allow electrocution, the gas chamber, hanging and firing squad. The gas chamber was last used in Arizona in 1999. A convict chose death by firing squad in Utah in 1996 (Idaho and Oklahoma also allow firing squads as the backup method to lethal injection. The last public hanging (and also the last public execution) occurred in 1936 in Kentucky. 2007-2008 Term: Boumediene v. Bush • • • • • • The Suspension Clause of Article I of the Constitution says “The privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” In Rasul v. Bush (2004) the Court held that the Constitution’s habeas corpus statute extends to noncitizen detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Congress responded to the Rasul decision by passing the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 (DTA), which essentially stripped courts of jurisdiction over habeas cases filed by Guantanamo detainees. The detainees insisted that the DTA did not apply to their cases, which were pending before its passage. The Supreme Court ultimately agreed, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006). Congress went back to the drawing board and passing the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA). The Act eliminates federal courts' jurisdiction to hear pending habeas applications from detainees. In the current case, the detainees argue that the MCA is unconstitutional under the Suspension Clause. 2007-2008 Term: District of Columbia v. Parker? • • • • • • • • The District of Columbia has asked the Supreme Court to uphold its strict 30year ban on keeping handguns in the home, setting up what could be a test of the Second Amendment with broad ramifications. The Second Amendment states: "A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed." The last Supreme Court ruling on the issue, Miller v. the United States (1939), is considered by many to define the right to bear arms as being given to militias, not to individuals. Initially U.S. District Judge Emmet G. Sullivan dismissed the lawsuit several years ago, ruling that the amendment was tailored to membership in a militia. But in a 2 to 1 decision in March 2007, a panel of judges for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled that the city's prohibition against residents keeping handguns in their homes is unconstitutional. Two judges said that while the District has a right to regulate and require registration of firearms it could not ban them in homes. The ruling also struck down a section of the law that required owners of registered guns, including shotguns, to disassemble them or use trigger locks. If the Court takes the case and strikes down the ban, similar gun laws in major cities, including New York, Chicago and Detroit, may be vulnerable. "Any accurate, unbiased reading of American history is going to come down to this being an individual right," said Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of the National Rifle Association. "To deny people the right to own a firearm in their home for personal protection is simply out of step with the Constitution." Former acting solicitor general Walter E. Dellinger III, who would argue the case before the Court, said, “This is not a law which takes away the rights to keep and bear arms. It regulates one kind of weapon: handguns.” Wayne LaPierre Walter Dellinger The Most Activist Supreme Court in History • • • • The Court is unafraid to decide the great issues of the day—even taking a presidential election away from the political process. In an August 11, 2007 speech to the American Bar Association, Justice Breyer explained that even when the Court makes unpopular decisions, the nation abides by them. In the 2000 election case of Bush v. Gore, Breyer noted, "there were no paratroopers, no rocks. ... People accepted it.“ Commenting on the 2006-2007 Term, Breyer said, “I had a difficult year. I was in dissent quite a lot, and I wasn’t happy.” In talking about the school decision, he said: “I wish I had won.” But he said that he was proud that this and other divisive issues are decided “in the courts, not in the streets.” Is Breyer right? Is it good that the Courts decide issues rather than the people? Consider… The Most Activist Supreme Court in History • • Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote a plurality opinion in the case of American citizen Yasser Hamdi who was captured in Afghanistan, designated an enemy combatant, held in a military brig in the U.S., and denied due process—despite the government’s failure to declare war or suspend habeas corpus. In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2006), O’Connor said that Hamdi could be held as long as hostilities continued in Afghanistan, but he must be granted an attorney and given the opportunity to go before a “neutral decision-maker” and given a chance to prove his innocence. Justice Scalia railed against what he saw as blatant judicial activism: “There is a certain harmony of approach in the plurality's making up for Congress's failure to invoke the Suspension Clause and its making up for the Executive's failure to apply what it says are needed procedures--an approach that reflects what might be called a Mr. Fix-it Mentality. The plurality seems to view it as its mission to Make Everything Come Out Right, rather than merely to decree the consequences, as far as individual rights are concerned, of the other two branches' actions and omissions. Has the Legislature failed to suspend the writ in the current dire emergency? Well, we will remedy that failure by prescribing the reasonable conditions that a suspension should have included. And has the Executive failed to live up to those reasonable conditions? Well, we will ourselves make that failure good, so that this dangerous fellow (if he is dangerous) need not be set free. The problem with this approach is not only that it steps out of the courts' modest and limited role in a democratic society; but that by repeatedly doing what it thinks the political branches ought to do it encourages their lassitude and saps the vitality of government by the people. Further Reading • • • Keck, Thomas M., The Most Activist Supreme Court in History (University of Chicago Press, 2004). Rosenberg, Gerald N., The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? (University of Chicago Press, 1993). Tushnet, Mark, Taking the Constitution Away from the Court (Princeton University Press, 2000).