Chapter 4 – wilhelm wundt and the founding of psychology

advertisement

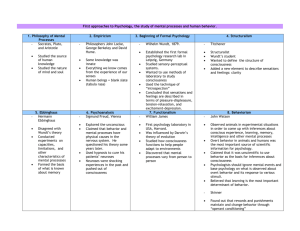

CHAPTER 6 – GERMAN PSYCHOLOGISTS OF THE 19TH & EARLY 20TH CENTURIES Dr. Nancy Alvarado German Rivals to Wundt Ernst Weber & Gustav Fechner -- psychophysicists Hermann Ebbinghaus -- memory Franz Brentano Carl Stumpf Oswald Kulpe Weber & Fechner Ernst Weber (1795-1878) Weber published “De tactu” describing the minimum amount of tactile stimulation needed to experience a sensation of touch – the absolute threshold. Using weights he found that holding versus lifting them gave different results (due to muscles involved). He used a tactile compass to study how two-point discrimination varied across the body. On the fingertip .22 cm, on the lips .30 cm, on the back 4.06 cm. Aesthesiometric compass Just Noticeable Difference (JND) Weber studied how much a stimulus must change in order for a person to sense the change. How much heavier must a weight be in order for a person to notice that it is heavier? This amount is called the just noticeable difference JND The JND is not fixed but varies with the size of the weights being compared. JND can be expressed as a ratio: DR k R where R is stimulus magnitude and k is a constant and DR means the change in R (D usually means change) Gustav Fechner (1801-1887) Fechner related the physical and psychological worlds using mathematics. Fechner (1860) said: “Psychophysics, already related to physics by name must on one hand be based on psychology, and [on] the other hand promises to give psychology a mathematical foundation.” (pp. 9-10) Fechner extended Weber’s work because it provided the right model for accomplishing this. Fechner’s Contribution Fechner called Weber’s finding about the JND “Weber’s Law.” Fechner’s formula describes how the sensation is related to increases in stimulus size: S k log R where S is sensation, k is Weber’s constant and R is the magnitude of a stimulus The larger the stimulus magnitude, the greater the amount of difference needed to produce a JND. He used catch trials to study guessing. Relationship of JND to Stimulus S.S. Stevens modified Fechner’s Log Law to a Power Function in the early 1950’s. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stevens%27_power_law Fechner’s Legacy His methods are still used in psychophysics. Ideas from signal detection theory have been applied to a wide variety of other topics. Threshold for criminal behavior, scenic beauty. Scaling techniques, including rating scales, were placed on a sound scientific basis, especially by S.S. Stevens later work, continued by Luce & Narens. His speculations about split-brain studies were confirmed by Sperry. Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909) Ebbinghaus was inspired by finding a copy of Fechner’s “Elements of Psychophysics.” He wanted to apply Fechner’s methods to study of higher mental processes. In 1877, he began developing procedures for studying memory. His major work, “Fundamentals of Psychology,” is dedicated to Fechner – “I owe everything to you.” Early Academic Career Ebbinghaus had no mentor to teach him techniques so he developed his own, highly original methods. He had no lab, no access to subjects, so he performed most experiments on himself. He followed rigorous experimental rules and spent 4 years replicating his first series of experiments. These were well received and widely recognized. His nonsense syllables were developed to avoid word familiarity, using a permutation formula. 19 consonants, 11 vowels, 11 consonants = 2299 Ebbinghaus Experiments First, he studied the relationship between the amount of material to be memorized and the time needed to learn it to complete mastery. His measure was number of repetitions needed. Second, he studied the effects of different amounts of learning on memory. His measure was savings – repetitions needed to relearn the original items after a delay. As repetitions increase, so does relearning time saved – overlearning helps. Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve His best known experiment studied the effects of passage of time on memory – his forgetting curve. In addition to graphing his data he developed a mathematical model by writing a logarithmic equation and deriving the parameters using the least squares method. He also compared means and variability and tested whether their differences exceeded chance. Other Investigations Ebbinghaus studied the relative effects on memory of spaced versus massed practice, part versus whole, and active versus passive learning. Active, spaced learning was most effective. He found that meaningful material was much easier to learn and remember than material without meaning – Don Juan poem vs nonsense syllables. Lists learned before sleep were better retained. Ebbinghaus’s Contributions This was the first time a higher mental function had been studied experimentally. His book is “one of the most remarkable research achievements in the history of psychology” Roediger. His success established a paradigm for studying memory that was used for the next 90 years. An ecological approach later challenged this: Ulric Neisser challenged validity of lab tasks. Bahrick studied long-lasting memories. Banaji & Crowder defended lab-based studies. An Applied Problem Breslau schools were concerned that children were too tired during an uninterrupted 8-1 school day. Griesbach tested mental fatigue and irritability using a two-point discrimination task. He proposed the day be broken into 2 short segments. Ebbinghaus disagreed because the measurement of sensory discrimination has little to do with mental activity, introducing the concept of content validity. He developed analogy and completion test items to measure intelligence, later included in IQ tests by Binet. Franz Brentano (1838-1917) Brentano was a Dominican priest and lecturer at the Univ. of Wurzburg who left his position after writing a scholarly critique of the doctrine of papal infallibility. During the next 6 years he taught at the University of Vienna and published a textbook:“Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint.” Comparison to Wundt Brentano studied Aristotle and put more emphasis on logical examination than experimental results. As a result, Brentano’s ideas were fixed and did not change, because neither logic nor premises change. Instead of studying the products of mental actions, as Wundt did, Brentano’s act psychology studied the processes and mental actions themselves. Brentano did not use introspection (inner observation) – it was impossible because the act of observing changes what is observed, retrospection (memory) was possible. Brentano’s Ideas About Mental Acts Three fundamental classes of mental acts: Ideating, judging, loving (versus hating) Mental acts may have as their objects past sensations (an idea of an object not present) using memory and imagination (Locke’s Reflection). It is possible to feel an emotion when the object of that emotion is not present. One mental act may have as its object another mental act – judgments about judgments. Brentano in Perspective Brentano is not as well-known as Wundt because he wrote less and had personal problems. He did very little experimental research. His main importance is his formulation of a rival approach to Wundt’s. His psychology of acts was a precursor to the American functionalists. Two of his students (Stumpf & von Ehrenfels) influenced the later Gestalt psychologists. Carl Stumpf (1848-1936) Stumpf was a talented musician who composed and performed throughout his life, mixing with musicians. Brentano changed his life by teaching him to think logically and empirically. Brentano encouraged him to transfer and study under Lotze, a German perceptual theorist. He became a priest but left the seminary over papal infallibility, but not the church like Brentano. Lotze got him a job at the Univ. of Gottingen where he worked with Weber and Fechner. The Golden Section Two quantities are in the golden ratio if the ratio of the sum of the quantities to the larger quantity is equal to the ratio of the larger quantity to the smaller one: ab a a b Stumpf conducted experiments studying whether this “golden section” ratio was aesthetically pleasing. Stumpf’s Early Work Stumpf gained a reputation for youthful brilliance by publishing a nativist explanation of depth perception. He opposed Berkeley, Helmholtz, Wundt & Lotze. He proposed that although “local signs” contribute to depth perception they are of secondary importance. The interpretive action of a higher center in the brain is most important. He paralleled Kant’s view of the nature of space. Stumpf’s Tone Psychology Like Brentano, Stumpf distinguished between phenomena and mental functions. He called sensory images, tones, colors phenomenology. Seeing, hearing, perceiving, thinking are cognitive acts. He studied sounds of musical instruments, melody, tonal fusion and consonance/dissonance of tones. He compared musical and non-musical people. His volume “Tone Psychology” appeared in 1883. This led to prestigious academic appointments. Debunking Sensational Phenomena In 1903-4, Stumpf challenged the likelihood of a machine that could change photographs of sound waves into sounds. In 1904 he chaired a commission to investigate the claims of Clever Hans, the horse who could count. His student, Oskar Pfungst, tested Hans when his owner knew the answer and again when he did not. The horse was correct 98% of the time in the first condition but 8% correct in the second condition. He was correct 89% without blinkers, 6% with blinkers. Clever Hans & Von Osten Von Osten was convinced that horses had inner speech and thus could do math. Stumpf’s Later Years His later years were sad. WWI emptied the university of young men who left to serve in the armed forces. War also disrupted his relationships with colleagues throughout Europe, including British, American and Russians, and caused his work to be overlooked. He was asked to organize psychologists to support the war effort but his heart wasn’t in the task. He retired in 1921, succeeded by Kohler. Oswald Kulpe (1862-1915) Kulpe studied history but became interested in psychology after hearing Wundt speak at Leipzig. At Wundt’s recommendation he went to Gottingen to study with Muller (Lotze’s successor as chair). Muller followed Fechner’s psychophysics and studied memory (interference) with Ebbinghaus – developing techniques for avoiding experimenter bias & demand. After graduating, he performed experiments challenging assumptions of Wundt & Titchener, although he had warm affection for Wundt. Kulpe’s Experimental Psychology Kulpe was influenced by Mach’s positivist philosophical views – all science is based on experience and naturalistic sensory observation. Mentalistic conceptions and attributions of mental entities are to be avoided. Psych needs objective descriptions of mental events. Kulpe tried to demonstrate that higher mental functions could be studied experimentally. Kulpe’s research provided a foundation for contemporary cognitive psychology. The “Wurzburg School” Founded by Kulpe & his students. Subjects were asked about free associations using a method of questioning called “Ausfrage.” Marbe studied “conscious attitudes” of subjects judging weights – doubt, hesitation, searching. Kulpe & Bryan (Clark University) showed that subjects could abstract features of nonsense syllables as an active mental act “apprehension.” Count the “F”s in a sentence. Investigations of Reaction Time Wurzburg psychologists asked how very fast, volitional reaction times could occur without being part of the subject’s mental experience. Watts used a more precise Hipp chronoscope & broke reaction times into four parts: (1) preparatory period, (2) stimulus presentation, (3) striving for the response, (4) the response itself. Based on introspection, the thinking takes place during the preparatory period (instructions), establishing a subject “set.” More Wurzburg Findings Using systematic experimental introspection, Ach found consistent differences between subjects – called decision types. Binet claimed priority based on descriptions of his kids. Later (1907), Buhler asked questions requiring thoughtful replies, not just “yes/no” answers. Subjects described imageless thought, where answers just came to them. Wundt claimed he was not using introspection correctly. Kulpe & Moore claimed meaning is distinct from image. Lost German Psychologists Why are only Ebbinghaus, Weber & Fechner well known? WWI disrupted others’ work and international contacts. WWII destroyed the German universities. Politics prevented communication between German and American psychologists. Cognitive psychology might have developed much sooner without this interruption. Only Gestalt psychology took root because some fled Nazi Germany and took refuge in America.