7 & 8

advertisement

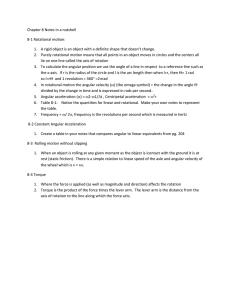

Chap. 7 – Rotational Motion (show slides as you move on) Definition of a radian (rad): 𝜃 𝑖𝑛 𝑟𝑎𝑑 = 𝑎𝑟𝑐 𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑔𝑡ℎ 𝑠 = 𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑖𝑢𝑠 𝑟 𝑚 [ ] 𝑚 Important: rad is dimensionless. Although it is not really a unit, we will use it as our official “unit” for angles, and angular displacement. Not degrees, not revolutions, etc. Remind students that the perimeter of a circumference is s = 2r, and so the angular displacement in radians when you complete a full circle is 2 (use the definition of radians above). radians 2 /4 degrees 360 180 45 revolution 1 ½=0.5 1/8=0.125 Remember the convention: CCW quantities are positive, CW quantities are negative. Practice “conversion of units” to adopt radians. Example: express 3200 rpm in rad/s. 3200 LINEAR/TANGENTIAL ∆𝑥 = 𝑥 − 𝑥0 𝑣̅𝑡 = ∆𝑥/∆𝑡 𝑎𝑡 = ∆𝑣/∆𝑡 [𝑚] [𝑚/𝑠] [𝑚/𝑠 2 ] 𝑟𝑒𝑣 2𝜋 𝑟𝑎𝑑 1 𝑚𝑖𝑛 ( )( ) = 335 𝑟𝑎𝑑/𝑠 𝑠 1 𝑟𝑒𝑣 60 𝑠 ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL ∆𝜃 = 𝜃 − 𝜃0 𝜔 ̅ = ∆𝜃/∆𝑡 𝛼 = ∆𝜔/∆𝑡 [𝑟𝑎𝑑] [𝑟𝑎𝑑/𝑠] [𝑟𝑎𝑑/𝑠 2 ] Important relations between LINEAR and ANGULAR quantities (only works in radians!): ∆𝑥 = 𝑟 ∙ ∆𝜃 [𝑚 = 𝑚 ∙ 𝑟𝑎𝑑] 𝑣𝑡 = 𝑟 ∙ 𝜔 [𝑚/𝑠 = 𝑚 ∙ 𝑟𝑎𝑑/𝑠] 𝑎𝑡 = 𝑟 ∙ 𝛼 [𝑚/𝑠 2 = 𝑚 ∙ 𝑟𝑎𝑑/𝑠 2 ] where 𝑣𝑡 is the linear velocity, and 𝑎𝑡 is the linear acceleration. The subscript “t” comes from the word tangential, because when objects move in circles, it makes more sense to refer to a tangential (coasting) velocity and acceleration, rather than linear. Check the units with the students in these equations, to make them understand that they can always derive these relationships by thinking of the units. Also, highlight that radian is not really a unit, but we write it as a reminder of a neutral angular definition. End of chapter problems: 1, 2, 3, 7, 13, 17 (leads to 𝑎𝑐𝑝 ) 7.4 Centripetal Acceleration ⃗ when moving in a circular path. 𝑎𝑐𝑝 is generated by the change in direction of the velocity vector 𝒗 For comparison, 𝑎𝑡 is generated by the change in magnitude of the velocity vector, in any path. The demonstration of the formula for centripetal acceleration comes from an analogy of triangles (show it quickly in the slides), for 𝑣 of constant magnitude: ∆𝑣 ∆𝑠 = 𝑣 𝑟 𝐶𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑑𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑏𝑦 ∆𝑡: ∆𝑣 ∆𝑠 𝑣 = ∙ ∆𝑡 ∆𝑡 𝑟 ∆𝑣 ∆𝑠 𝑣 = 𝑎𝑐𝑝 𝑤𝑒 𝑔𝑒𝑡: 𝑎𝑐𝑝 = ∙ ∆𝑡 ∆𝑡 𝑟 ∆𝑠 𝐼𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑡 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑛 ∆𝑡 → 0, 𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑛 → 𝑣 𝑎𝑛𝑑 ∆𝑡 𝑎𝑐𝑝 𝑣2 = 𝑟 Notice from the triangle with ∆𝑣 that the direction of ∆𝑣 is radial (inward), and so is the direction of the centripetal “center-seeking” acceleration 𝑎𝑐𝑝 . Relation with other angular and linear quantities: 𝑎𝑐𝑝 = 𝑟𝜔2 2 + 𝑎2 𝑎𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 = √𝑎𝑐𝑝 𝑡 Centripetal Force Newton’s 1st Law, the law of equilibrium, stated that when 𝐹𝑛𝑒𝑡 = 0, then 𝑣 = 0 or 𝑣 = 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡. Well, in a circular path 𝑣 ≠ 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡 because its direction is always changing (even if the magnitude remains constant). Therefore, we are in the realm of Newton’s 2nd Law when moving in a circular path: there will be a net force! The centripetal force will be this net force. The centripetal force is not a new force. It’s just a new name we give to the net force that is pointing in a radial direction (see figure) when a body is moving in a circular path. 𝐹𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑅𝐴𝐷𝐼𝐴𝐿 = 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝑚𝑎𝑐𝑝 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝑚𝑎𝑐𝑝 = 𝑚 𝑣2 𝑟 Instruct students that it is necessary to draw force diagrams again. The way to find the net force is to visualize first all forces acting on a body. Some typical centripetal force problems (draw force diagrams): A pebble spinning in a circle (string is horizontal): 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝑇 Weight spinning in a circle (line is not horizontal; figure): 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝑇 cos 𝜃 Turning a corner with a car: 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝑓 Driving on a banked road (figure): 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝐹𝑁 sin 𝜃 At the bottom of a roller coaster loop: 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝐹𝑁 − 𝐹𝑔 At the top of a roller coaster loop, if upright: 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝐹𝑔 − 𝐹𝑁 At the top of a roller coaster loop, if upside-down: 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝐹𝑔 + 𝐹𝑁 Critical speed: It is when the object is about to lose contact with the surface making 𝐹𝑁 → 0. In general then, 𝐹𝑐𝑝 = 𝐹𝑔 and 𝑣𝑐𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 = √𝑅𝑔 End of chapter problems: 18, 25, 23 (ST), 27 (ST), 31, 32 (ST), 68, 75 (ST) In general, we skip Sections 7.5 and 7.6 in PHY101 because of time constraints. Chap. 8 – Rotational Dynamics (show slides as you move on) Torque LINEAR/TANGENTIAL ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL 𝜏𝑛𝑒𝑡 [mN] 𝐹𝑛𝑒𝑡 [N] torque will describe the describe the change in linear change in rotational motion motion I use a wall cabinet door to demonstrate how the door closes differently when applying the same F in different parts of the door. Highlight that F is not enough to describe rotational motion, 𝑟 is needed. Then I apply the same F at the same 𝑟, but at different angles, to highlight the 𝜃 dependency. Relation between 𝐹 and 𝜏 (no dot or cross products in PHY101): |𝜏| = |𝑟| ∙ |𝐹| ∙ sin 𝜃 To make things straightforward, I instruct the students to search for the smallest formed between 𝐹 and 𝑟 (or the extension of 𝑟), so that 0 90, and sin will always give a positive number. For example, in the figure on the left, I instruct PHY101 students to pick ’ instead of . In my experience, it is easier when they know they should look for angles 90. Students should then assign a + or value to the torque according to the CCW + and CW convention (when looking from above). I teach them how to use the righthand rule by curling the fingers when going from 𝑟 to 𝐹 : if thumb points up, it’s positive, otherwise it is a negative torque. 𝜏𝑛𝑒𝑡 = ∑ 𝜏 We only work with two directions of torque in Chapter 8: either positive (CCW) or negative (CW). It is like 1-d motion in Chapter 2. End of chapter problems: 1, 2, 3, 4 (ST) Center of mass (CM) Why teach this in PHY101? The force of gravity acts in all parts of an extended body, but we can represent it as an arrow coming down from the center of mass. In fact, the center of mass is the natural axis of rotation of bodies, if they are freely falling. If we hold a rigid extended body by its CM, it will not rotate because when you apply a force where r = 0, there is no torque. Explain that this is all about finding the (x, y) coordinate of the average distribution of mass. It is a formula for weighted averages, just like the formula used to calculate students’ final grades. Wherever there is more mass, that point will have a greater weight in the averaging process. 𝑥𝐶𝑀 = 𝑥1 ∙ 𝑚1 + 𝑥2 ∙ 𝑚2 + 𝑥3 ∙ 𝑚3 + ⋯ ∑ 𝑥𝑖 ∙ 𝑚𝑖 = 𝑚1 + 𝑚2 + 𝑚3 + ⋯ 𝑚𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑦𝐶𝑀 = 𝑦1 ∙ 𝑚1 + 𝑦2 ∙ 𝑚2 + 𝑦3 ∙ 𝑚3 + ⋯ ∑ 𝑦𝑖 ∙ 𝑚𝑖 = 𝑚1 + 𝑚2 + 𝑚3 + ⋯ 𝑚𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 Important: emphasize that the denominator is the total mass, regardless of the fact that you may not be using all masses in the numerator: they all need to go in the denominator (must be the absolute total mass). End of chapter problems: 11, 13 Rotational 1st Law LINEAR/TANGENTIAL 𝐹𝑛𝑒𝑡 = 0 condition for linear equilibrium ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL 𝜏𝑛𝑒𝑡 = 0 condition for rotational equilibrium Use both together for COMPLETE condition of equilibrium in problems from now on. End of chapter problems: 7, 12, 19, 21 (ST), 22 (ST). Moment of inertia and rotational 2nd Law LINEAR/TANGENTIAL m [kg] mass 𝐹𝑛𝑒𝑡 = 𝑚𝑎 2nd Law: linear form ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL 𝐼 = ∑ 𝑚𝑖 ∙ 𝑟𝑖2 [kgm2] moment of inertia or rotational inertia 𝜏𝑛𝑒𝑡 = 𝐼𝛼 where 𝛼 = 𝑎 𝑟 2nd Law: rotational form Use a disk and a hoop with the same mass to demonstrate that one will always roll faster than the other (improvise a ramp, ask students to catch objects). Highlight to students that mass is not enough to understand how objects rotate or roll, we need I. We talk about the fact that I represents the distribution of mass in respect to the axis of rotation. We have other devices (e.g. inertia blue and red rods) to demonstrate that the rotational inertia also changes depending on the position of the axis of rotation. In summary, I depends on both a) shape of body, b) location of axis of rotation. For extended bodies, students are instructed to look for formulas at the Table in their textbook (it will be made available during test). For punctual bodies, students must calculate the rotational inertia directly by: 𝐼 = ∑ 𝑚𝑖 ∙ 𝑟𝑖2 (examples in the slides) End of chapter problems: 31, 32 (ST), 35 (like Example 8.11 – emphasis because this application is very challenging to students), 36, 39 Rotational kinetic energy LINEAR/TANGENTIAL 1 𝐾𝐸𝑡 = 2 𝑚𝑣 2 [J] ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL 1 𝐾𝐸𝑟 = 2 𝐼𝜔2 [J] of the center of mass about the axis of rotation Use both KE from now on: 𝐾𝐸𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 = 𝐾𝐸𝑡 + 𝐾𝐸𝑟 It takes energy to make a body move forward, but it also takes energy to make it rotate. When a body rolls, there’s a combination of linear (forward motion as visualized by looking only at the center of mass) and rotational (spin about the center of mass) motions. Thus, both KE’s need to be taken into account. End of chapter problems: 44, 51, 49, 45 (ST), 52, 47 Angular momentum LINEAR/TANGENTIAL ANGULAR/ROTATIONAL |𝐿| = |𝑟𝑝𝐶𝑀 | = |𝐼𝜔| 𝑝 = 𝑚𝑣 [kgm2/s] about the axis of rotation [kgm/s] of the center of mass ⃗ = 𝐼𝜔 𝐿 ⃗ for a punctual mass: |𝐿| = 𝑟 ∙ 𝑚 ∙ 𝑣 ⃗ is also conserved in rotational Just like 𝑝 was conserved in an isolated system, 𝐿 motion when 𝜏𝑒𝑥𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑛𝑎𝑙 = 0 ∑ 𝐿⃗𝑖 = ∑ 𝐿⃗𝑓 or ∑(𝐼𝜔 ⃗ )𝑖 = ∑(𝐼𝜔 ⃗ )𝑓 Demonstrations: ⃗ : use rotating platform or stool, and dumbbells. Open and close arms while spinning. Conservation of 𝐿 ⃗ is a vector: step on the rotating platform carrying a bicycle wheel spinning horizontally (so that 𝐿 ⃗ 𝐿 ⃗ on the blackboard, and highlight that it must stay points up or down: draw the arrow of the initial 𝐿 constant in the isolated platform environment). Flip the wheel 180, and you will start to spin as well (you were initially at rest on top of the platform). Draw on the board the arrows that represent the ⃗ 's, combining the motions of the wheel and yours. Refer to the use of gyroscopes in spacecrafts. final 𝐿 Spin the bicycle wheel as fast as possible and show how it is easier to hold it with a finger or two when it is spinning (stability when riding a bike). Students may notice the precession, which can be introduced at this point. In general for PHY101 we skip precession. There would be more to say, but in general at this point we are out of time. Besides, this really covers what is important and what is necessary. End of chapter problems: 57, 56, 60, 61, 58, 72 Test 5.