Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

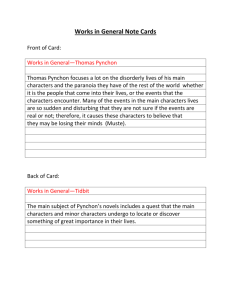

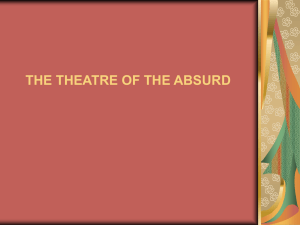

Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice Abstract Little discussion exists regarding the relationship between paranoia, anti-paranoia and the Absurd, and the combined influence they have on Thomas Pynchon’s central characters. This thesis will seek to illuminate to what extent Pynchon instils paranoia within the absurd reality imposed upon the central character in Inherent Vice during his quest. The thesis will begin by discussing the relationship between paranoia, anti-paranoia and the Absurd, followed by the Absurd quest prevalent in Pynchon’s fiction. Then Humour of the Absurd, or Black Humour, central to Pynchon is described. The Absurd quality of the California setting will be elaborated upon next. Finally, the Absurd quest itself is traced extensively throughout Inherent Vice by following its main character, Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello. Along his quest, analysis shows that Doc rarely becomes aware of the absurd, and that his paranoid conviction supplies the pretense of meaning sought after in Absurdist reality, in a similar fashion to how anti-paranoia has been rejected by a number of Pynchon’s previous characters. Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Paranoia, Anti-paranoia and the Absurd p. 3 2 The Absurd Quest p. 7 3 Humour of the Absurd p. 10 4 California Dreaming and the Absurd p. 11 Setting 5 The Quest in Inherent Vice p. 14 Conclusion p. 25 Works Cited p. 27 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Introduction Critics, such as Elaine B. Safer, Leo Bersani and Don Hausdorff, have addressed the occurrence of paranoia, anti-paranoia and also the presence of Absurdist elements within the fiction of Thomas Pynchon. However, there is a lack of discussion concerning the possible relation between these three themes and their relevance to the perception of Pynchon’s characters. Moreover, these aspects are integral to the nature of the quest plot central to most of his novels. However, despite that paranoia and Absurdism contain similar elements, they are not identical. Both paranoia and Absurdism essentially concern the search for meaning in a world that is otherwise unbearable. Relatively little criticism is available on Pynchon’s more recent work Inherent Vice, and therefore a thesis based upon this novel would contribute to academic discussion. This thesis will seek to illuminate to what extent Pynchon instils paranoia within the absurd reality imposed upon the central character in Inherent Vice during his quest. The thesis will consist of three sections: the first will attempt to explain Pynchon’s notion of paranoia and its counterpart, anti-paranoia in previous works by Pynchon and their relationship with Absurdism, described by Albert Camus and Thomas Nagel. The second section will deal with the Absurd quest central to Pynchon, illustrated in light of the previous section. The third section will discuss the humour of the Absurd. Although critics, such as Kellman, label Pynchon as a Black Humour writer, no distinction is apparent. The fourth section will describe the setting of Inherent Vice, which is integral to the absurdity and the consequent humour present. Finally, the fifth section will directly deal with the Absurd quest in Inherent Vice. I: Paranoia, Anti-Paranoia and the Absurd “He understood it to be another deep nudge from forces unseen,” writes Thomas Pynchon about Zoyd Wheeler in the opening lines of Vineland. Implied is that these unseen forces are secretive and capable of influencing Zoyd, prompting the very paranoid thought that they may well be out to get 3 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 him. This introduces the paranoid mentality which possesses most of Thomas Pynchon’s characters throughout his novels. Paranoia is described as “more generally: any unjustified or excessive sense of fear; esp. an unreasonable fear of the actions or motives of others” (OED “paranoia”). However, Bersani argues that in Pynchon, paranoia functions more “as if it were merely synonymous with something like unfounded suspicions about a hostile environment” (99). Therefore, Pynchon’s paranoia essentially stems from the perception of a threatening entity. The paranoid seeks connections and “other orders behind the visible” (qtd. in Bersani 100), which conspire against him. These forces unseen range from having one’s erections monitored as a pre-determiner of V-2 rocket strike sites due to Pavlovian conditioning during childhood, as is the case with Slothrop in Gravity’s Rainbow, to Sportello’s suspicion in Inherent Vice that the theft of his porn magazines is a conspiracy catering to his sexual tastes. Paranoia is omnipresent in Pynchon’s work, containing “‘every degree of paranoia from the private to the cosmic… a mentality which assumes ‘the existence of a vast, insidious, preternaturally effective international conspiratorial network designed to perpetrate acts of the most fiendish character’" (Sanders 178). Events are suspect for the paranoid and Pynchon describes that this stems from “‘the discovery [note: the ‘discovery,’ not the ‘suspicion’] that everything is connected, everything in the Creation’" (qtd. in Bersani 102). Hindrances are related to a perpetrator, or indeed, as is a frequent joke, to the perpetrator behind the perpetrator, “the mob behind the mob” (Inherent Vice 248). Paranoia desires connections leading to a controlling force, and ultimately, to a global conspiracy. Paranoia “offers the ideally suited hypothesis that the world is organized into a conspiracy, governed by shadowy figures whose powers approach omniscience and omnipotence, and whose manipulations of history may be detected in every chance gesture of their servant” (Sanders 177). Within this context, according to Louis Mackey, Pynchon orders his fictional world along the lines of “all men are either Elect, the handful chosen for salvation, or Preterite, passed over and tacitly 4 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 consigned to damnation” (17). This instils the conviction that the forces unseen strive to realise the individual’s predetermined damnation, and therefore paranoia “substitutes for the divine plan a demonic one” (Sanders 178). According to David Cowart, the notion of conspiracy and the consequent anxiety is engrained within 60s America (7), an atmosphere which Pynchon explores. In lieu of the series of assassinations of the Kennedys, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King “‘the American public began to suspect, like Oedipa Maas in the Crying of Lot 49, that ‘it’s all part of a plot, an elaborate [...] plot’” (Cowart 7). This suspicion seems to be rooted in the inability of the public and Pynchon’s characters to understand society, resulting in a continuous search for a motive or a connection between events that unravels them all. Molly Hite argues that “Pynchon's fiction is driven by the trope of the absent centre, in the form of a central insight illuminating a unitary idea of order” (qtd. in Simons 211). Therefore, “both Pynchon's key characters and his readers become involved in unfulfilled searches for the underlying logic of the world or the novel, or searches for… a total theory” (Simmons 211), stemming from the “the subjective difficulty of representing the power of global capitalism” (211). For Pynchon’s characters, the existence of a global conspiracy depends more on the inability to understand the magnitude of global capitalist society, fundamentally lacking a central guiding entity. Pynchon’s characters, therefore, exist in paranoid reality. However, the opposite may also be true, termed by Pynchon as anti-paranoia: “if there is something comforting-religious, if you want, about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long" (qtd. in Bersani 103). Either everything is related or nothing is, which Brian McHale explains as: “paranoia and anti-paranoia, the world as over-interpretable and as uninterpretable: these are the poles between which Pynchon's characters, plots, represented world, and narrative voice oscillate...” (223). Due to the characters’ inability to understand the driving force within their society they continuously oscillate between two, perhaps equally absurd, conclusions on 5 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 reality. Anti-paranoia is deemed more terrifying than paranoia, because malign reason is preferred by Pynchon’s characters to a lack of reason. "‘Either they have put him here for a reason,’ Slothrop speculates during ‘the anti-paranoid part of his cycle,’ ‘or he's just here. He isn't sure that he wouldn't, actually, rather have that reason’" (qtd. in Bersani 103). Reason is therefore necessary to cope with reality, even if only in the guise of “hidden orders behind the visible” (Bersani 103). Therefore, paranoia is the source of meaning and the “desired structure of thought” (Bersani 103). Pynchon’s characters strive to make sense of the world, yet are unable to do so. Moreover, Pynchon suggests that paranoia is desirable because it at least grants the pretense of meaning in life. Both states of being seem absurd. Thomas Nagel writes that “the sense that life as a whole is absurd arises when we perceive, perhaps dimly, an inflated pretension or aspiration which is inseparable from the continuation of human life and which makes its absurdity inescapable, short of escape from life itself” (718). It is the inherent lack of meaning that is absurd and unbearable for Pynchon’s characters. Absurd is defined as “the chaotic and purposeless nature of the universe, and the futility of human attempts to make sense of it” (OED). Albert Camus describes the absurd struggle for meaning in a world that is inherently meaningless in “The Myth of Sisyphus”: “this world in itself is not reasonable... But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart” (7). The desire for reason is similar to Pynchon’s paranoia. Moreover, Nagel writes that “if there is a philosophical sense of absurdity, however, it must arise from the perception of something universal-some respect in which pretension and reality inevitably clash for us all” (718). Anti-paranoia shares similar doubt, wherein significant connection becomes arbitrary. However, Slothrop chooses paranoia and so does Absurdism advocate not succumbing to the futility of the individual. Instead, the individual applies meaning, even if only as a pretense to make the situation of life bearable. Therefore, paranoia and Absurdism concern the 6 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 means with which to cope in world that is otherwise unbearable, if only essentially by means of pretension. II: The Absurd Quest in Pynchon Paranoia, then, seeks connection in the world in order to establish meaning and reason in the form of forces unseen. Absurdism is a consequence of the futile search for meaning in a meaningless world. Similarly to anti-paranoia, Absurdism expresses the disconnection between the individual’s relation to the world and arbitrariness in action. As a consequence of this awareness, paranoia and Absurdism share the theme of a quest for knowledge and of being. This quest is undertaken even if only as a pretense to distract the individual from succumbing to the realisation that truly no forces are at work. Safer writes that: Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, like Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), and V. (1963), directs attention, with sharp-edged humor, to people’s quest for meaning and fulfilment in the twentieth century, a time when many have become upset by the repeated failure of their dreams and aspirations. This continued yearning and frustration helps set up an absurd perspective, absurd by Camus’ definition, which focuses on a “divorce between the mind that desires and the world that disappoints, [the] nostalgia for unity, this fragmented universe and the contradiction that binds them together.” (107) The continued yearning and frustration are central to the absurd quest. Camus writes in the Myth of Sisyphus that the "mind's deepest desire is an insistence upon familiarity, an appetite for clarity”. Within Absurdism, the individual seeks knowledge in order to understand and Camus continues, “Understanding the world for a man is reducing it to the human, stamping it with his seal”. The inhumanity of the world and its consequent incomprehensibleness is that which causes frustration within the Absurd. Moreover, Camus states, “the mind that aims to understand reality can consider 7 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 itself satisfied only by reducing it to terms of thought”. This echoes Pynchon’s paranoia, wherein events in the world are reduced to humanised intent because that is understandable within the structures of capitalist society. The Absurd quest consists of consists of a journey in which epistemological and ontological questioning is integral. According to Brian McHale, epistemological and ontological questioning is central to Pynchon’s fiction, due to “an increasing perception that the world and reality are unstable, and therefore there is no point in questing for reliable knowledge” (McHale). Pynchon’s characters are nearly always wound up in a quest to uncover, or to discover, but of which the goal degrades into abstraction and only questions of being remain. Safer states that “in Pynchon’s earlier novels, the main characters, and the reader as well, search for life’s meaning and for hope. Slothrop (in Gravity’s Rainbow), Oedipa Maas (in The Crying of Lot 49), and Stencil (in V.) quest for some form of order (no matter what kind) and fulfilment in the face of absurdity” (107). The absurd quest is manifested within Herbert Stencil in V.. Herein, Stencil quests after V., an elusive entity he comes across in his father’s secret intelligence papers, believing V. to be connected to global conflict. Herbert’s father, Sidney, notes that “there is more behind and inside V. than any of us had suspected. Not who, but what: what is she” (qtd. in Hausdorff 259). In the style of the absurd quest, Pynchon’s “‘single central image is abstract, the letter ‘V.,’ which subsumes multiple meanings… and undergoes a number of transformations in the course of the narrative’” (259). In the end, perhaps the most viable explanation for V.’s elusiveness is that V. is simply non-existent. Integral to the quest is the problem of interpretation. According to Hite “Pynchon exploits the idea that ‘things ought to add up to’ such an ordinary signified in order to motivate the quest for unity and meaning amidst chaos... what Pynchon exploits is the cultural determination of the desire for complete certainty in all things” (qtd. in Madsen20). The quest for unity and meaning requires interpretation to find it: all connections must add up to some form of unified truth. 8 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 The absurd quest may then be nothing more than the search for order within disorder. As Cowart writes “Pynchon ultimately reveals nothing more than the entropic acceleration of disorder. No pattern palliates our plight” (7). Yet, despite the apparent futility, the characters persist on their quest. It is in this that the absurdity of the quest may be recognised. The quest is futile: Herbert will never find V. as a tangible and satisfying resolution to his searching. However, Hausdorff writes that, though “meaningless the search may be, it is self-propelling, providing its own rationale. Most terrifying is the possibility that he might discover V.; in that event, the search and the activity would end, and he would be forced to lapse into inertness” (263). Echoed here is Camus and his myth of Sisyphus, wherein Sisyphus persists in lifting the rock up the mountain as that task gives temporary him purpose. According to Hausdorff, it is this sense of purpose that is important, whether in terms of survival or the search for individual meaning. This is “‘the legitimate alternative to the ‘inertness’ of modern man in a mechanized world” (268). The act of questing in itself grants meaning and purpose to life. Therefore, the absurd quest is also a personal undertaking, wherein Pynchon describes numerous individuals who, in the face of a meaningless society, embark upon a purpose of their own. “God knows, how many Stencils have chased V. about the world” (qtd. in Hausdorff 266). However, Pynchon also suggests that this quest is not a viable solution, as it is “no more and no less a depersonalized obsession than all the others” (266). Obsession still does not grant Pynchon’s characters any real purpose in life. When the quest is over, the world will again become meaningless. The notion of pretense, as discussed earlier in paranoia and Absurdism, is therefore present within the nature of the absurd quest. Pynchon suggests that the quest is a privilege, “the world doesn’t care” (qtd. In Hausdorff 266). The opposite reality would be unbearable, and indeed Hausdorff writes “viable delusion thus becomes a survival tactic in a world running out of alternatives” (268). The 9 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 absurd quest, therefore, involves the futile desire of unity and order, and yet this personal undertaking becomes the only viable alternative, or delusion, to a meaningless world. III: Humour of the Absurd In Inherent Vice, humour plays a central role in depicting the absurdity that Pynchon’s characters encounter during their quest. Their environment is constantly distorted by absurdity, causing the characters to struggle with disorientation. Moreover, the absurd situations force not only the characters, but more so the reader to rethink their stance on what is accepted as normative and what is real. The presented absurdity is often humorous and therefore, in this section, the relevance of Pynchon’s humour to the Absurd quest and the humour ingrained in the absurd environment will be discussed. Pynchon’s writing tends to be categorised as Black Humour, a movement in which “the novels and stories written by such authors as Pynchon, John Barth, Joseph Heller, Bruce Jay Friedman, and Gilbert Sorrentino, among others, tended to present events that were grim and terrifying but to deal with them in a wildly humorous manner” (Kellman). The more tragic and confrontational realities of the world are coupled with humour and Jerome Klinkowitz explains that black humour writing arose as “an accommodation by laughter to the world's insanity and a deliberate refusal to find any new forms in fiction appropriate to the strange new worlds they described” (271). Black humour writing explores the inherent absurdity of man’s place in the world, thereby depicting its senselessness and the disorientation caused for its characters. The absurd, therefore, is prevalent within black humour and indeed O’Neil writes, “the absurd finally, insofar as it is a comic rather than a tragic mode, is always an expression of black humour, and even in its tragic emphasis remains a fertile source of latent entropic humour. All the forms of black humour discussed so far, in short, tend ultimately towards the absurd...” (160). 10 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Moreover, the absurd may even impose black humour. H.S Reiss, on Kafka’s Absurdism, writes that Kafka’s humour suggests “the need for an acceptance of life which then can be a way out of an otherwise hopeless maze” (536). Similar to in Pynchon’s writing, Kafka’s maze implies the disorientation of the characters, and it seems to be Kafka’s hope that humour will bring about the acceptance which turns the world from a senseless maze into a world that simply is. Nagel, too, argues that the absurd confrontation “need not be a matter for agony unless we make it so” (727). This confrontation is actuated “by the collision between the seriousness with which we take our lives and the perpetual possibility of regarding everything about which we are serious as arbitrary or open to doubt... These two inescapable viewpoints collide in us, and that is what makes life absurd” (Nagel 718-719). Humour arises from this undermining of the seriousness in which man undertakes life and, more importantly, is regarded as the only option when confronted with absurd reality. Therefore, Reiss writes that humour within Kafka’s writing is necessary to accept the human condition, as “through it man’s intolerable burden can be eased and the human situation accepted” (541). The Absurd perspective necessitates humour in order to cope with its senselessness, allowing for black humour to arise. IV: California Dreaming and the Absurd Setting Set in California, more specifically in Los Angeles with a brief excursion to Las Vegas, the setting saturates Inherent Vice with the humorously absurd. Located at the edge of the American frontier, the Pacific edge, California is distinguishable from the rest of the United States as a “testament to the exhaustion of the westering impulse once seen as so vital to the nation's manifest destiny... from the Old world to New” (Adams 252). California in this sense is regarded as the ultimation of the American Dream: the “cultural symbolism as America’s America” (Miller 226). Pynchon uses California as a writing surface onto which “alternate versions of past and present are being inscribed” (Miller 226). 11 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 California possesses a “collective dream that everybody was being encouraged to stay dripping in” (Inherent Vice 176). Los Angeles is implied to be about to boil over and is, in the style of Pynchon, “over drugged and hyper signified” (Wilson 222). Hyper signified in the sense that all incidents attain a higher significance – which may amount to nothing but superstition in this drugged state. Within his writing Pynchon suggests that the dream is unsustainable and self-corrupting: It was as if whatever had happened had reached some kind of limit. It was like finding the gateway to the past unguarded, unforbidden because it didn’t have to be. Built into the act of return finally was this glittering mosaic of doubt. Something like what Sauncho’s colleagues in marine insurance liked to call inherent vice. “Is that like original sin?” Doc wondered. “It’s what you can’t avoid,” Sauncho said... (351). It is this mosaic of doubt that makes suspect the underlying truth to California dreaming. Miller writes that California is depicted as a “sleek beauty masking inescapable corruption, disillusionment and emptiness”. California possesses a rotten core: the inherent vice that Doc struggles with as a private investigator. Adams describes Pynchon’s California as a place of “automization” (251), and Los Angeles an overwhelming city which lacks a central core and therefore its very structure produces alienation and disorientation (254). The inhabitants, Pynchon’s Preterite, struggle in the immoral city as can be discerned when in the closing scenes of the novel Doc finds himself “in a convoy of unknown size, each car keeping the one ahead in taillight range, like a caravan in a desert of perception, gathered awhile for safety in getting across a patch of blindness” (368). Miller describes this scene as representing the inescapability from the “common feeling of powerlessness” (236), and even this specific act of common good, which Doc notes is “was one of the few things he’d ever seen anybody in this town, except for hippies, do for free” (36), is merely a “temporary ‘safety’” (Miller 236). Moreover, this blind movement through the fog illustrates the disorientation with which the characters wrestle as they navigate through the story. Pynchon suggests that California – this 12 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 place of dreaming – is soulless and absurd. Beneath the surface lies an inescapable fatality: an inherent vice with which Pynchon confronts his characters and urges them onward as if by forces unseen. The detour to Las Vegas is also significant because, according to Jan Kott, the slot machines in casinos are the ideal situation for the Theatre of the Absurd because all elements are present: “Alienation is complete. Man is reduced to a player… Man is "thrown"… into a world which does not belong to him… Their relationship is absurd. The machine controls the player rather than the player the machine” (17-18). Pynchon, therefore, is able to infuse his paranoia into an immediately familiar Absurdist setting. Pynchon presents California in Inherent Vice through the focalisation of the central protagonist, Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello, which the reader follows throughout the novel. Due to this single focalisation, the story is limited to Doc’s perspective on reality, which consequently lends the reader first hand insight into the disorientation inflicted by drug induced Californian absurdity. Moreover, there is an aspect of unreliability due to Doc being an avid stoner, only increasing the hallucinogenic experience of California. His perspective also allows for elements of drug humour, important in Pynchon and tinged by absurdity. Through Doc, then, the reader is directly confronted with the absurd conditions Pynchon presents. However, it is noteworthy that despite that Doc encounters absurdities; it is only the reader who seems to be fully aware of their absurd nature. The reader is dropped into Doc’s California lifestyle and seems to be expected to, like Doc, accept the absurdities present within it, to humorous effect. His reality is littered with humorous incongruities that Doc seems not to notice. It is this sense of reader omniscience that is an important aspect within the Theatre of the Absurd. In the Theatre of the Absurd “ spectators see the happenings on the stage entirely from the outside, without ever understanding the full meaning of these strange patterns of events, as newly arrived visitors might watch life in a country of which they have not yet mastered 13 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 the language” (Esslin 5). This shows that Doc is an Absurd character: confined to the patterns, or the lack thereof, that dictate the workings of his reality. It is only through sporadic humorous inclination that Doc fleetingly becomes aware of the absurdity and thus experiences absurd realisations. The reader, however, is continually aware, and therefore, similarly to the spectators of the Theatre of the Absurd, “are thus confronted with a grotesquely heightened picture of their own world: a world without faith, meaning, and genuine freedom of will” (Esslin 6). IV: The Quest in Inherent Vice In the previous sections the nature of the Absurd quest in Pynchon’s novels has been explained, as has the significance of Pynchon’s choice of a California dreaming setting in relation to the absurd. Also described has been the humour contained within Pynchon’s writing, humour that is, according to Kafka and Nagel, necessary in coming to terms with the absurd. The thesis will now turn to the Absurd quest within Inherent Vice, which takes on the form of an investigation into the disappearance of Wolfmann, Shasta, Coy and the illicit nature of the Golden Fang. The significance of the encountered absurdity and paranoia will be described by following Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello to specific absurd sites along his quest. The first of such places Doc visits is Chick Planet Massage, where, upon entering, Doc is immediately approached by Jade who informs him of “today’s Pussy-Eater’s Special, which is all good until closing time?” (20). Besides that Jade constantly ends her sentences as a question, it seems absurd that at this massage parlour a customer is able to pay to provide a sexual favour for the hostess. It is a humorous incongruity to the expected, as is common in Inherent Vice. Doc doesn’t come to this same conclusion and accepts the nature of the offer by replying with “Mmm, not that $14.95 ain’t a totally groovy price, but I’m really trying to locate this guy who works for Mr. Wolfmann?” (20). Another absurdity is that the place turned out to be “bigger inside than out” (21), 14 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 with Doc roaming endlessly through vacant rooms. This spatial incongruity is another recurring aspect and adds to the sense of disorientation in Doc’s wandering. Doc heads towards the Wolfmann residence in order to talk to Mickey’s wife, Sloane. The encounter between Doc and Sloane is described with “as if auditioning for widowhood, Sloane Wolfmann strolled in from poolside wearing black spike-heeled sandals, a headband with a sheer black veil, and a black bikini of neglible size made of the same material as the veil. She wasn’t exactly an English rose, maybe more like an English daffodil...” (57). This is another incongruity: Sloane’s clothes don’t match the expectations of a woman in mourning, which the black veil and black clothing denote, especially in the context of her kidnapped husband. Her bikini is out of place and a satire on Californian clothing and relationships. All in all, Sloane strikes an absurd figure. Doc, again, seems to merely accept this portrayal, commenting that “miniskirts were invented for young women like her” (57). Doc also comes across Wolfmann’s personal necktie collection consisting of silk ties bearing images of various women in erotic positions, women that Doc suspects are a part of “a Mickey Wolfmann girlfriend inventory” (63). These clothing articles provide an incongruity: ties are part of a professional dress code, and yet an erotic depiction violates this purpose. Instead, they function more as conquest tokens. Doc’s reaction to Sloane’s erotic image is his observation of “an almost gentlemanly angle to Mickey’s character he hadn’t counted on” (64). Though humorous, Doc again appears unfazed by the encountered absurdity. Moreover, Shasta’s tie is missing, another piece of the puzzle to be solved. Riggs Warbling’s talks about zomes at the residence, which he designs and builds, making “great meditation spaces, do you know, some people have actually walked into zomes and not come back out the same way they went in? And sometimes not at all? Like zomes are portals to someplace else. Especially if they’re located out in the desert, which is where I’ve been...” (62). Zomes are absurd insofar that they distort space and time, creating a form of transportation out of current 15 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 reality. Riggs’ absurd descriptions fit in with the rest of the Californian hallucinogenic experience, making zomes the perfect Californian home. Later on in the quest, zomes reappear out in the desert at Arrepentimiento, Wolfmann’s “long time dream project… near Las Vegas” (62). The site is dotted by “several what Riggs had called zomes, linked by covered walkways. Not perfect hemispheres, but pointed at the top” (249). At one of these Doc and Tito are arrested by Riggs, who threatens them with “all right, you can stop there… Or you can keep on coming, clear on into the next world. Ask me if I give a shit” (250). This threat is ironic as Riggs invites them into a zome and later on once again informs Doc that zomes “can act as doorways to other dimensions” (253). Either way, Doc may have entered another world. Similarly to Chick Planet Massage, the interior of the zome is disorientating in terms of volume: “and actually, now that Doc thought of it, more space, judging from the outside than there could possibly be in here. Riggs caught him looking around and read his mind. ‘Groovy ain’t it?... instead of a few dollars per cubic foot enclosed, this is more cubic feet per dollar” (251). Zomes are a transportation device, in the sense that Riggs adds “I can leave whenever I want.’ He motioned with his head. ‘All I have to do is step through that door over there, and I’m safe’” (253). This suggests that zomes provide an escape: from California and perhaps, too, from its inherent vice. Indeed, the name of the site, Arrepentimiento, is “‘Spanish for ‘sorry about that’”(248). It is a free housing project and Wolfmann’s attempt to pay penance for the means in which he acquired his wealth; his sought-for release from the inherent vice he has been a part of. Shasta can also be linked to these zomes. Back at Gordita Beach, Doc encounters Shasta, who explains that she had had to go “up north? Family stuff?” (262) and that she had merely “been away (262)”. Doc notes that Shasta wears around her neck a seashell “maybe even brought back from a distant Pacific island, whose shape and markings reminded Doc of one of the zomes in Mickey’s now-abandoned project in the desert” (262). A zome again symbolises a portal, which in this case served to transport Shasta either away – to the Golden Fang schooner – or back again. Whether or not zomes actually function as 16 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 portals, the signification behind the increasing number of zomes that Doc encounters is striking. If the number of zomes increases, then so too, Doc may reason, does the number of L.A inhabitants who wish to leave the relentless city. This might be, in Doc’s paranoia, because the corrupt forces unseen within the city are coming to their culmination. After the Wolfmann residence comes Topanga mansion, where the surf band the Boards resides. The Boards are a very successful band in California and represent the music industry in Inherent Vice. Yet, Doc comments on the disconsolateness of success within this aspect of the Californian dream: “Doc was reminded for the uncountableth time that for every band like this one there were a hundred or a thousand others like his cousin’s band Beer, doomed to shuffle in obscurity, energised by a faith in the imperishability of rock ‘n’ roll...” (126). Pynchon comments on California’s music industry: for most of the Pynchon’s preterite the dream of success only exists as a tragic hope. Within the mansion, Doc meets a number of absurd characters, for instance, a dog named Myrna who shows very un-doglike behaviour. The dog watches television with other inhabitants and due to some “strange dog ESP” (127), she can tell that a dog-food commercial is about to come on a minute before it does. When it is over, she “‘would turn her head to any humans in the vicinity and nod emphatically... it seemed to be more of a social act, along the lines of, ‘something, huh?’” (128). Topanga mansion contains a certain sense of inertness which slowly develops throughout the passage. Myrna is watching television along with the Boards and Spotted Dick personnel, among which “the concentration level among the viewers had doc feeling a little restless. He realised the scope of the mental damage one push on the “off” button of a TV zapper could inflict on this roomful of obsessives” (128). Pynchon uses this scene to comment on the effects of television and the absurdity it instils: the inhabitants appear lifeless and disconnected, exemplified by their concentration level, as if television provides an alternate version of reality. Moreover, television 17 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 appears to have a brainwashing effect, as the watchers seem “absorbed enough... to forget that these people are actors” (128). Paranoia and the forces unseen are present in Topanga mansion. Doc becomes aware of a harbouring and paranoid atmosphere, describing that “something like a security detail appeared now and then out on the property, making perimeter checks” (128). Although some form of security is to be expected for a celebrity band, a perimeter check remains a little strange for a house filled essentially by drug users, partygoers and groupies. It is when talking to Spotted Dick’s keyboard player Smedley, that Doc discovers a threatening presence: “How’s Fiona enjoying it here in Southern California?” Smedley got glum. “Loves everything but the paranoia, man.” “Paranoia, really?” His voice dropped to a whisper. “This house—” At which point a scowling young gent... entered and leaned against a wall with arms folded and just stayed there, listening. Smedley, his eyeballs oscillating wildly, fled the area (128). Doc realises that a controlling power is present, unnatural to the maintained hippie vibe: “Doc couldn’t help but noticing what you’d call an atmosphere. Instead of a ritual handshake or even a smile, everybody he got introduced to greeted him with the same formula — “where are you at, man?’ suggesting a high level of discomfort, even fear, about anybody who couldn’t be dropped in a bag right away and labeled’” (129). Labels are an element of control: everyone must adhere to an orderly system of categorisation. This implies an amount of brainwashing on the hippies’ part by forces unseen, whether through television, the music industry or drugs. Moreover, Doc’s paranoia stretches out past the mansion to greater Los Angeles, wherein he describes that he has become increasingly aware of “older men, there and not there, rigid, unsmiling, that he knew he’d seen before, not the faces necessarily but a defiant posture, an unwillingness to blur out, like everybody 18 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 else at the psychedelic events of those days, beyond official envelopes of skin” (129). For Doc, these men are instruments of the forces unseen, “like the operatives who had dragged away Coy Harlingen” (129), who threaten the Californian dream. “If everything in this dream of prerevolution was in fact doomed to end and the faithless money-driven world to reassert its control over all the lives it felt entitled to touch, fondle and molest, it would be agents like these, dutiful and silent, out doing the shit work, who’d make it happen” (130). It is the continued working of the described money-driven world that establishes the inherent vice present within Californian society. Their agents infiltrate even the most exclusive of surfer community: the mansion of surfer band the Boards. Coy, too, has been silenced by these forces, “a look on his face so desperate, so longing, and way too nervous, as if somehow inside this house he had actually been forbidden to speak” (131). It is in the final absurd scenes of the Topanga mansion that the workings of the forces unseen culminate; namely, in zombification. After speaking with Coy, Doc and Denis smoke a joint with other party members, during the course of which they become immensely stoned. However, this leads to a terrible hallucination because “because Doc knew now, beyond all doubt, that every single one of these Boards was a zombie...” (132). Indeed this drug induced realisation causes panic and “Doc suddenly found himself fleeing through the corridors of the creepy mansion with uncertain numbers of screaming flesh-eating creatures behind him...” (133). Doc, Denis, and by chance meeting also Jade, manage to escape unharmed, rolling a joint “to keep from freaking out?” (134) as they drive away headed for Santa Monica. Drugs, music, television and the forces unseen have turned the inhabitants of the mansion into zombies. Topanga mansion may be discerned as Pynchon’s metaphor for the realities concerning Los Angeles’ society: impotent, paranoid and consisting of soulless zombified members who are, as Doc expresses, “undead and unclean”(132). It may be better California dreaming to not exist at all, as expressed in Denis’ reaction to the Doc’s unclean zombies: “dead and clean is okay?” (132). The superficiality of California dreaming is zombify-ing and 19 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 something to escape from. Moreover, Topanga mansion presents a blurring of boundaries between real and imagined, which raises the question of whether Californian dreaming is a viable reality or a viable delusion. Next is the coincidence – or not – of Doc finding the Golden Fang headquarters by looking up an old address an Ouija board gave him years ago in order to score marihuana with Shasta. The building itself is “in the old L.A. tradition of architectural whimsy, this structure was supposed to be a six-story-high golden fang!” (168). A golden fang shaped building is absurd, but indeed as Doc himself points out, it only maintains L.A. tradition. Dr. Blatnoyd explains to Doc that the Golden Fang is merely “a syndicate, most of us happen to be dentists, we set it up years ago for tax purposes, all legit...” (169). It is absurd for a syndicate of dentists to construct a fang shaped building, especially on the dubious presumption of legitimate tax purposes. Moreover, though, Dr. Blatnoyd’s explanation also indicates the illusiveness of the Golden Fang. The Golden Fang continuously refuses to be pinned down as a distinct and identifiable entity and Sportello wonders to himself “let’s see – it’s a schooner that smuggles in goods. It’s a shadowy holding company. Now it’s a Southeast Asian heroin cartel. Maybe Mickey’s in on it. Wow, this Golden Fang, man – what they call many things to many folks...” (159). Sportello is becoming lost in the possibility of the Golden Fang, an entity reminiscent of the forces unseen and the “mob behind the mob” (248).Therefore, the Golden Fang is absurd as it functions more as a concept, rather than an entity. The Golden Fang is there for Doc to figure out, yet it does not supply answers. Another humorous absurdity is that after Dr. Blatnoyd offers Doc lines of cocaine after determining that Doc is “one of those hippie dopefiends” (169), Doc discovers a manual on Dr. Blatnoyd’s desk. The manual is titled Golden Fang Procedures Handbook and is opened on a section titled “Interpersonal Relationships. Section Eight – Hippies” (170). Herein is described that “dealing with the Hippie is generally straightforward. His childlike nature will usually respond positively to drugs, sex and/or rock and roll, although in which order these are to be deployed must 20 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 depend on conditions specific to the moment” (170). Through this Pynchon comments on the possible simplicity in which Doc’s forces unseen manage to exert control and the lack of free will that Doc seems to possess. Dr. Blatnoyd uses cocaine to control Doc, and therefore drugs in this “overdrugged” (Wilson 222) state are implied to be a source of docility used by the forces unseen on the inhabitants. Moreover, this confirms Doc’s prior suspicions that “like something else was going on – something... not groovy” (170). This building, representational of Californian absurdity, is corrupt. Doc learns that Wolfmann may be an inmate in a mental institute called Chryskylodon. Tito informs Doc that it is Greek meaning golden fang. Chryskylodon presents questions of sanity and confinement within Inherent Vice. Doc is able to enter as a guest on tour. During lunch, Doc notices that the white wine he’s drinking really has more of a yellow colour than white. Attempting to check the label he “‘noticed an ingredient list several lines long, with the note, in parentheses, ‘continued on back of bottle,’ but whenever he tried, as casually as he could, to have a look at the label on the back, he noticed he was getting these stares, and sometimes people even reached and turned the label away so he couldn’t read it’” (187). Not knowing the contents of the wine, Doc and perhaps even the entire table have now been drugged, making their current lucidness questionable. More importantly, Doc’s sanity is undermined by the doctors through their act of turning away the label. Doc’s attempt at reading the label is made to appear out of the ordinary, as something not done. The reverse is also true; the doctors’ acceptance of the absurd wine bottle and their attitude towards Doc’s scepticism is crazy. Another question of sanity is when Doc encounters an orderly who is wearing “the exact tie Doc had failed to find in Mickey’s closet, the one with Shasta hand-painted on it, in a pose submissive enough to break an ex-old man’s heart, that’s if he was in the mood” (190). By wearing the erotic tie the orderly’s professionalism is violated, making his, and therefore all the workers, sanity questionable. 21 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Coy Harlingen, too, is present at the institute, who Doc encounters to his utter surprise in the Chryskylodon’s meditation grotto. This is odd as being an inmate; Coy is expected to be confined to the premises. However, Doc has occasionally encountered Coy outside of the institute. The spatial confines are therefore put into doubt as the door may simply be open, which results in Chryskolodon being depicted as an absurd confinement. Reminiscent of the Topanga zombies, Coy and Doc manage to talk by avoiding suspicion as long as they walk “slow and stoned” (191). It is through Coy that Doc learns of the Golden Fang’s scheme of “vertical integration” (192). If the Golden Fang, essentially drug dealers, “could get its customers strung out, why not turn around and also sell them a program to help them kick?” (192). This system is effective and would continue unhindered “as long as American life was something to be escaped from” (192). Drugs are therefore again depicted as an element of control. The Golden Fang has truly invested in the inherent vice of Los Angeles. The disillusionment behind California dreaming forces its seekers to find solace through other means: drugs. Coy again manages to simply vanish before Doc’s eyes. At a later stage, Doc arrives at the Nine of Diamonds casino in Las Vegas. The casino setting, naturally, plays with the idea of probability and chance. Doc is out to find Puck Beaverton and his partner Einar, who has “these hypersensitive hands… that can feel through the lever, feel the exact point where each of them reels lets go one by one” (226). This means that Einar exerts control over the game and does not depend on luck. As a result, Puck and Einar run a scheme: Einar wins and Puck collects. Doc catches Einar winning on a machine as “a quantity of JFK half-dollars began to vomit out of the machine in a huge parabolic torrent… Einar nodded and stepped away…” (231). Einar is therefore capable of beating the ideal absurd situation. However, as is typical of Pynchon, misfortune still strikes “when suddenly the laws of chance, deciding on a classic fuck-you, instructed Puck’s nickel machine also to hit... At which point Puck, as if allergic to dilemmas, broke for the nearest exit” (231-232). Puck is unable to choose from which machine to collect the winnings and consequently 22 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 wins nothing. Pynchon uses this as a metaphor to describe Puck’s lack of free will: the forces unseen have decided that both machines are an option. As such, Pynchon provides the perfect allegorical situation for Absurd theatre, dismantles it, and then, adhering to his incongruous writing, again humorously illustrates the unpredictability and misfortune of the world by having Puck and Einar win simultaneously. Moreover, Doc’s reaction to witnessing this scene is simply to “claim what looked by now to be several cubic feet of nickels” (232). Public image is absurd in Los Angeles. At the handoff between Doc and the Golden Fang operatives, the latter come disguised as “a wholesome blond California family in a ’53 Buick Estate Wagon... a nostalgic advertisement for the sort of suburban consensus...” (349). This description is clearly ironic and again presents an incongruity due to that the operatives are disguised as the unsuspected suburban dream family. This should only increase the paranoia and distrust present within Doc’s view of society. Humorously absurd is Doc’s perfect civility towards the dad, offering him “a hand with this?” (349). Moreover, though, this shows that Los Angeles’ inherent vice and the forces unseen have almost whimsically infiltrated the most secure of both American and Californian values: that of family. Doc’s questing is briefly put into doubt along the way. At one point on the beach Shasta makes Doc wonder to himself “Shasta had nailed it. Forget who – what was he working for anymore?” (314). It is through this questioning that Doc fully realises the Absurd nature of his lifestyle. Doc doesn’t usually work for cash customers, but instead “assumed he’d been out busting his balls for folks who if they paid him anything it’d be half a lid or a small favor down the line or maybe only just a quick smile, long as it was real” (314).Instead, Doc works in a transaction of favours and a sense of decency for something worth his while and this is what supplies Doc with meaning, if not any material wealth. The memory of Shasta and the favour she asked is enough to spur him on. 23 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 The final passage of the novel describes Doc driving along the existential highway and missing all the exits due to the heavy fog: Then again, he might run out of gas before that happened, and have to leave the caravan, and pull over on the shoulder and wait. For whatever would happen. For a forgotten joint to materialise in his pocket. For the CHP to come by and choose not to hassle him. For a restless blonde in a Stingray to stop and offer him a ride. For the fog to burn away, and for something else this time, somehow, to be there instead (369). Due to the resolution of his absurd quest, Doc now briefly lacks purpose and meaning, but in a spirit similar to Camus’ Sisyphus, he is content until the next quest, the next challenge is nudged out of the fog by forces unseen. 24 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Conclusion Pynchon’s paranoia throughout his novels is reminiscent of the Absurd as described by Camus and Nagel, as both share unmistakably similar theme illustrating the struggle that man faces without a clearly existent ordering entity. Within Inherent Vice, Larry ‘Doc’ Sportello is the character portrayed to brave this struggle in the form of an Absurd quest: an undertaking granting purpose, and at times, serving only as a viable delusion in a meaningless world. Doc must pursue the Golden Fang in the hopes of restoring Shasta. Even at the quest’s conclusion, the Golden Fang remains an enigmatic force, one that surpasses mere paranoia and is an actual powerful entity. Moreover, they seem to only be a part of California’s inherent vice. Absurdity within Inherent Vice is commonly presented through humorous incongruity. These incongruities often violate established meaning, such as Sloane’s bikini mourning and Wolfmann’s ties. However, only the reader is aware of the humorous absurdity as Doc is simply accepting. Disorientation is a key aspect to depicting Doc’s struggle along the quest, often presented through spatial distortion, such as represented by absurd constructions such as zomes. Highways symbolise the unknown journey of the quest and the lack of meaningful destination. Paranoia and the forces unseen, often presented within absurd situations, such as the zombification at Topanga mansion. Moreover, California dreaming is depicted as an Absurdist reality as it is questioned to be a viable reality, or a viable delusion. In this regard, sanity, also, is questioned. A clearly recognisable Absurdist setting is presented at the casino in Las Vegas. The relation between free will and the notion of probability and chance are commented upon at this stage. The actual resolution of the quest does not particularly relieve Doc, nor grant him a permanent sense of fulfilment. Doc does not gain anything, and only waits for the next quest to come along and give him a temporary sense of purpose, which bears similarity to Camus’ absurd Sisyphus. 25 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 This thesis sought to illuminate to what extent Pynchon instils paranoia within the absurd reality imposed upon the central character in Inherent Vice during his quest. Paranoia is almost omnipresent in Inherent Vice, and by extent also in the depicted absurd reality. The Absurd depicts frustration of desiring meaning in a meaningless world. Paranoia, in a sense, provides this sense of meaning. It is Doc’s paranoid conviction of meaning and signification that, in a way, prevents him from becoming explicitly aware of the Absurd, unlike the reader. Only at times does he question the nature of his quest, yet this doubt is quickly dispelled. Along his quest, analysis shows that Doc rarely becomes aware of the absurd, and that his paranoid conviction supplies the pretense of meaning sought after in Absurdist reality, in a similar fashion to how anti-paranoia has been reject by a number of Pynchon’s previous characters. However, although an absurdist trend may be discerned, it would not be correct to say that Pynchon truly is an absurdist writer in the same way as playwright Samuel Beckett or writer Albert Camus is. A main problem in the comparison would be that in Pynchon’s writing his characters substitute the inherent absence of structure with another paranoid form of ordering entity. Consequently, paranoia is more of a self-imposed reality, rather than one that is. Absurdism only seeks to discover how an individual is able to deal and live with the absurdity inherent to their existence. It does not replace the absence of an ordering entity with paranoid suspicion. This thesis sought to illustrate Thomas Pynchon’s iconic themes of paranoia and antiparanoia and to present these themes in relation to Absurdism, and Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, a more recent novel that has yet to be discussed extensively. In future reference, Pynchon may be compared and contrasted to well-established Absurdist writers, or other works containing absurd and possibly drug induced elements, such as Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. Moreover, the development of the Absurd as a contemporary theme present in literature may be studied, in order to establish whether Absurdism truly is a state of being inherent to the modern world. 26 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 Works Cited “absurd, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2015. Web. "paranoia, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2015. Web. Adams, Rachel. "The Ends of America, the Ends of Postmodernism.” Twentieth Century Literature (2007): 248-272. Bersani, Leo. “Pynchon, Paranoia and Literature.” Representations (1989): 99-118. Camus, Albert and Patricia Holburd Heidenheimer. "The Myth of Sisyphus.” Fulcrum Press, 2007. Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus, and other essays. 27 May 1955. Web. Cowart, David. "Pynchon and the Sixties.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction (2010): 3-12. Esslin, Martin. The Theatre of the Absurd. Bloomsbury Publishing, 17 June 2015. Web. Gordon, Jeffrey. "Nagel or Camus on the Absurd?” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (1984): 15-28. Hausdorff, Don. "Thomas Pynchon's Multiple Absurdities.” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature (1966): 258-269. Kellman, Steven G. "Thomas Pynchon American Literature Analysis". Masterpieces of American Literature, 17 June 2015. Web. Klinkowitz, Jerome. "Review: A Final Word for Black Humor.” Contemporary Literature (1974): 271276. Mackey, Louis. “Paranoia, Pynchon and Preterition.” SubStance (1981): 16-30. 27 Floris Heidsma # 4028120 BA THESIS Paranoid Detection: The Absurd Quest in Inherent Vice English Language and Culture Supervisor: Simon Cook Word Count: 8306 McHale, Brian. "Review: Writing about Postmodern Writing.” Poetics Today (1982): 211-227. —What Was Postmodernism? Open Humanities Press. Web. Miller, John. "Present Subjunctive: Pynchon's California Novels.” Critique Studies in Contemporary Fiction (2013): 225-237. Nagel, Thomas. "The Absurd.” The Journal of Philosophy (1971): 716-727. O'Neill, Patrick. "The Comedy of Entropy: the Contexts of Black Humour.” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature (1983): 145-166. Pynchon, Thomas. Inherent Vice. New York: The Penguin Press, 2009. Reiss, H. S. "Franz Kafka's Conception of Humour.” The Modern Language Review (1949): 534-542. Safer, Elaine B. "Pynchon's World and Its Legendary Past: Humor and the Absurd in a TwentiethCentury Vineland.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction (1990): 107-125. Sanders, Scott. "Pynchon's Paranoid History.” Twentieth Century Literature (1975): 177-192. Simons, Jon. "Postmodern Paranoia? Pynchon and Jameson.” Edinburgh University Press (2000): 207221. Wilson, Rob. "On the Pacific Edge of Catastrophe, or Redemption: California Dreaming in Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice.” Boundary (2010): 217-225. 28