Chapter Three

advertisement

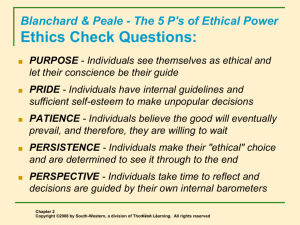

Chapter Three Ethical Principles, Quick Tests, And DecisionMaking Guidelines Copyright © 2003 by SouthWestern, a division of Thomson Learning 1 Chapter Topics 1. 2. 3. Decision criteria for ethical reasoning Ethical relativism: A self-interest approach Utilitarianism: A consequentialist (results-based) approach 4. Universalism: A deontological (duty-based) approach 5. Rights: An entitlement-based approach 6. Justice: Procedures, compensation, retribution 7. Immoral, amoral, and moral management 8. Four social responsibility roles 9. Individual ethical decision-making styles 10. Quick ethical tests 11. Concluding comments Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 2 Decision Criteria for Ethical Reasoning A first step in addressing ethical dilemmas is to identify the problem and related issues. Laura Nash developed twelve questions to ask yourself during the decision-making period to help clarify ethical problems. These twelve questions can help individuals: Openly discuss the responsibilities necessary to solve ethical problems Facilitate group discussions Build cohesiveness and consensus Serve as an information source Uncover ethical inconsistencies Help a CEO see how managers think Increase the nature and range of choices Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 3 Decision Criteria for Ethical Reasoning The following three criteria can be used in ethical reasoning: Moral reasoning must be logical Factual evidence cited to support a person’s judgment should be accurate, relevant, and complete Ethical standards used should be consistent A simple but powerful question can be used throughout your decision-making process in solving ethical dilemmas: What is my motivation for choosing a course of by action? Copyright © 2003 South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 4 Decision Criteria for Ethical Reasoning A major aim of ethical reasoning is to gain a clearer and sharper logical focus on problems to facilitate acting in morally responsible ways. Two conditions that eliminate a person’s moral responsibility for causing harm are: Ignorance Inability Mitigating circumstances that excuse or lessen a person’s moral responsibility include: A low level of or lack of seriousness to cause harm Uncertainty about knowledge of wrongdoing The degree to which a harmful injury was caused or averted Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 5 Ethical Relativism: A Self-Interest Approach Ethical relativism holds that no universal standards or rules can be used to guide or evaluate the morality of an act. This view argues that people set their own moral standards for judging their actions. This is also referred to as naïve relativism. The logic of ethical relativism extends to culture. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 6 Ethical Relativism: A Self-Interest Approach Benefits include: Problems include: Ability to recognize the distinction between individual and social values, customs, and moral standards Imply an underlying laziness Contradicts everyday experience Relativists can become absolutists Relativism and stakeholder analysis. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 7 Utilitarianism: A Consequentialist (ResultsBased) Approach The basic view holds that an action is judged as right, good, or wrong on the basis of its consequences. The moral authority that drives utilitarianism is the calculated consequences or results of an action, regardless of other principles that determine the means or motivations for taking the action. Utilitarianism includes other tenets. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 8 Utilitarianism: A Consequentialist (ResultsBased) Approach Problems with utilitarianism include: No agreement exists about the definition of the “good” to be maximized No agreement exists about who decides How are the costs and benefits of nonmonetary stakes measured? Does not consider the individual Principles of rights and justice are ignored Utilitarianism and stakeholder analysis. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 9 Universalism: A Deontological (Duty-Based) Approach This view is also referred to as deontological ethics or nonconsequentialist ethics and holds that the means justify the ends of an action, not the consequences. Kant’s principle of the categorical imperative places the moral authority for taking action on an individual’s duty toward other individuals and humanity. The categorical imperative consists of Copyrighttwo © 2003 parts. by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 10 Universalism: A Deontological (Duty-Based) Approach The major weaknesses of universalism and Kant’s categorical imperative include: Principles are imprecise and lack practical utility Hard to resolve conflicts of interest Does not allow for prioritizing one’s duties Universalism and stakeholder analysis. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 11 Rights: An EntitlementBased Approach Moral rights are based on legal rights and the principle of duty. Rights can override utilitarian principles. The limitations of rights include: Can be used to disguise and manipulate selfish, unjust political interests and claims Protection of rights can be at the expense of others Limits of rights come into question Rights and stakeholder analysis. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 12 Justice: Procedures, Compensation, Retribution The principle of justice deals with fairness and equality. Two recognized principles of fairness that represent the principle of justice include: Equal rights compatible with similar liberties for others Social and economic inequality arrangement Four types of justice include: Compensatory Retributive Distributive Procedural Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 13 Justice: Procedures, Compensation, Retribution Problems using the principle of justice include: Justice, rights, and power are really intertwined. Two steps in transforming justice: Who decides who is right and who is wrong? Who has moral authority to punish? Can opportunities and burdens be fairly distributed? Be aware of your rights and power Establish legitimate power for obtaining rights Justice and stakeholder analysis. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 14 Immoral, Amoral, Or Moral Management Immoral management means intentionally going against ethical principles of justice and of fair and equitable treatment of other stakeholders. Amoral management happens when others are treated negligently without concern for the consequences of actions or policies. Moral management places value on equitable, fair, and just concern of others involved. Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 15 Four Social Responsibility Roles Figure 3.3 illustrates four ethical interpretations of the social roles and modes of decision-making. The four social responsibility modes reflect business roles toward stockholders and stakeholders. Two social responsibility orientations of businesses and managers toward society include: Stockholder model Stakeholder model Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 16 Individual Ethical Decision-Making Styles Stanley Krolick developed a survey that interprets individual primary and secondary ethical decision-making styles, that include: Individualism Altruism Pragmatism Idealism Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 17 Quick Ethical Tests The Center for Business Ethics at Bentley College suggests six questions to be asked before making a decision. Classical ethical tests: The Golden Rule The Intuition Ethic The Means-End Ethic Test of Common Sense Test of One’s Best Self Test of Ventilation Test of Purified Idea Copyright © 2003 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning 18