Transformations: Lynn Enterline and Chaucer, Wife of Bath*s

advertisement

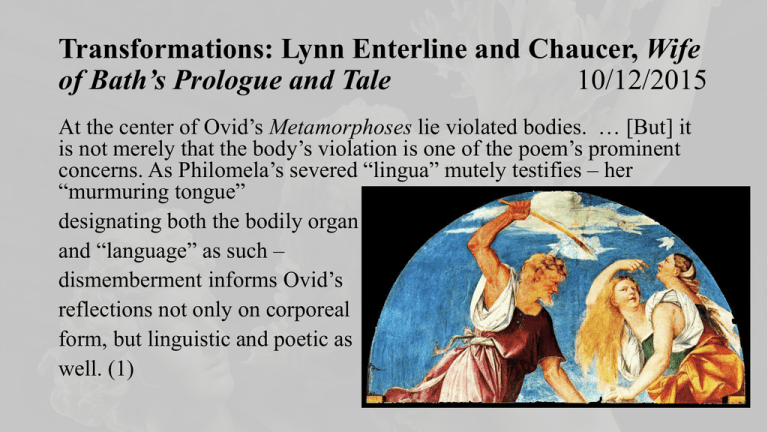

Transformations: Lynn Enterline and Chaucer, Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale 10/12/2015 At the center of Ovid’s Metamorphoses lie violated bodies. … [But] it is not merely that the body’s violation is one of the poem’s prominent concerns. As Philomela’s severed “lingua” mutely testifies – her “murmuring tongue” designating both the bodily organ and “language” as such – dismemberment informs Ovid’s reflections not only on corporeal form, but linguistic and poetic as well. (1) In this book, I contend that the violated and fractured body is the place where, for Ovid, aesthetics and violence converge, where the usually separated realms of the rhetorical and the sexual most insistently meet. (1) I analyze the complex, often violent, connections between body and voice in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and several Renaissance texts indebted to it. (1) My general purpose is twofold: to interrogate the deeply influential connections between rhetoric and sexuality in Ovid’s text; and to demonstrate the foundational, yet often disruptive, force that his tropes for the voice exert on early modern poetry, particularly on early modern representations of the self, the body, and erotic life. (2) I have chosen texts in which desecrated and dismembered bodies are imagined to find a way to signify, to call us to account for the labile, often violent, relationship between rhetoric and sexuality … (2) Ovid’s stories fascinate contemporary feminists writing about female subversion and resistance much as they once did medieval and early modern writers preoccupied with love and male poetic achievement. (2) [A]n important hallmark of Ovidian narrative … is its unerring ability to bring to light the often occluded relationships between sexuality, language, and violence.(2) I open this study with the example of Philomela’s amputated, “murmuring” tongue because it so succinctly captures the characteristic way that Ovid uses stories about bodily violation to dramatize language’s vicissitudes. (3) [V]iolated bodies ... provide Ovid with the occasion to reflect on the power and limitations of language as such. Before being cut out, for instance, Philomela’s tongue speaks about rape as a mark of the difference between what can and cannot be spoken: she says “I will move even rocks to share knowledge” of an act that is. literally, ne-fas, or “unspeakable” … (3) Elissa Marder: “One cannot speak ‘rape,’ or speak about rape, merely in terms of the physical body. The sexual violation of the woman’s body is itself embed in discursive and symbolic structures.” (cited 3) When Tereus “speaks the unspeakable,” language becomes a productive, violent act that is compared to rape even as the act of rape resists representation. (3-4) Nefas stresses that all we get, from Philomela or the narrator, are mere words or signs about an event that escapes words and signs. Resistance to narration, however, only induces further narrative. Thus when Tereus literalizes his “unspeakable” act by cutting out her tongue, giving her an “os mutum” line 574 --- literally, “speechless mouth” – Philomela finds recourse in art, weaving a tapestry to represent the crime. (4) Like her narrator, Philomela struggles at the limits of representation: where the narrator stutters at the effort to turn an unspeakable act into verse, Philomela is imagined to coax an expert weaving out of an unintelligible, hence “barbarous,” instrument. (4) The work that Philomela produces … amplifies the problems raised by her “moving” tongue: her tapestry takes up where her tongue left off, telling us that in this story presumed distinctions between language and action, the speakable and the unspeakable, aesthetics and violence verge on collapse. On her tapestry, Philomela weaves a set of purple “notae,” a noun that … suggests several divergent yet crucial meanings. Nota may signify a written character – a mark of writing used to represent “a sound, letter, or word.” It may signify the “vestige” or “trace” of something, like a footprint. It may also designate a mark of stigma or disgrace, particularly an identifying brand on the body. And in the plural form … “notae” can, by extension, also suggest “a person’s features.” (4-5) Through her murmuring tongue and bruised marks Ovid invites us to reflect on the power and limitations of language in its several overlapping functions: instrumental, poetic, and rhetorical.” (5) As an instrument of communication .. Language is necessary but inadequate to its task. As a sign hovering between literal and figural meanings, Philomela’s “lingua” or “tongue” functions as productive yet potentially violent distortion of the world (and body) it claims to represent. On Philomela’s loom, signs become objects of aesthetic appreciation. And as a rhetorical tool, language wields enormous power, although its force may, without warning, exceed the control of the one who uses it. The figure of Philomela’s severed “lingua” and her bruised “purple notes” … refuse any final distinction between language and the body, or between ideas and matter. (5) To understand why Ovidian poetry insists on drawing such close connections between language, sexuality, and violence, this book directs attention back to the often overlooked scene of writing in the Metamorphoses. By “scene of writing” I am referring to two, related, matters: the poem’s systematic selfreference, its complex engagement with its own figural language and with the fact of having been a written rather than a spoken epic; and its equally complex engagement with the materiality of reading and writing practices in the Roman world. (6) The opening of the Wife of Bath’ s Tale. The Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales. San Marino, Huntington Library. The Prologe of the Wyves Tale of Bathe The Middle English text is from Larry D. Benson., Gen. ed., The Riverside Chaucer, 3rd edn (Boston: Houghton Miflin Company, 1987).Interlinear translation and text from here: https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/wbt-par.htm 1 "Experience, though noon auctoritee 2 Were in this world, is right ynogh for me 3 To speke of wo that is in mariage; 4 For, lordynges, sith I twelve yeer was of age, 5 Thonked be God that is eterne on lyve, 6 Housbondes at chirche dore I have had fyve -7 If I so ofte myghte have ywedded bee -- "Experience, though no written authority Were in this world, is good enough for me To speak of the woe that is in marriage; For, gentlemen, since I was twelve years of age, Thanked be God who is eternally alive, I have had five husbands at the church door – If I so often might have been wedded – 8 And alle were worthy men in hir degree. 9 But me was toold, certeyn, nat longe agoon is, 10 That sith that Crist ne wente nevere but onis 11 To weddyng, in the Cane of Galilee, 12 That by the same ensample taughte he me 13 That I ne sholde wedded be but ones. 14 Herkne eek, lo, which a sharp word for the nones, 15 Biside a welle, Jhesus, God and man, 16 Spak in repreeve of the Samaritan: And all were worthy men in their way. But to me it was told, certainly, it is not long ago, That since Christ went never but once To a wedding, in the Cana of Galilee, That by that same example he taught me That I should be wedded but once. Listen also, lo, what a sharp word for this purpose, Beside a well, Jesus, God and man, Spoke in reproof of the Samaritan: 17 `Thou hast yhad fyve housbondes,' quod he, `Thou hast had five husbands,' he said, 18 `And that ilke man that now hath thee `And that same man that now has thee 19 Is noght thyn housbonde,' thus seyde he certeyn Is not thy husband,' thus he said certainly. 20 What that he mente therby, I kan nat seyn; What he meant by this, I cannot say; 21 But that I axe, why that the fifthe man But I ask, why the fifth man 22 Was noon housbonde to the Samaritan? Was no husband to the Samaritan? 23 How manye myghte she have in mariage? How many might she have in marriage? 24 Yet herde I nevere tellen in myn age I never yet heard tell in my lifetime 25 Upon this nombre diffinicioun. A definition of this number. 26 Men may devyne and glosen, up and doun, Men may conjecture and interpret in every way, 27 But wel I woot, expres, withoute lye, But well I know, expressly, without lie, 28 God bad us for to wexe and multiplye; God commanded us to grow fruitful and multiply; 29 That gentil text kan I wel understonde. That gentle text I can well understand. 30 Eek wel I woot, he seyde myn housbonde Also I know well, he said my husband 31 Sholde lete fader and mooder and take to me. Should leave father and mother and take to me. 32 But of no nombre mencion made he, 33 Of bigamye, or of octogamye; 34 Why sholde men thanne speke of it vileynye? But he made no mention of number, Of marrying two, or of marrying eight; Why should men then speak evil of it? St Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum (c. 393 AD) 1.13. Let us run through the remaining points … But and if you marry, you have not sinned. It is one thing not to sin, another to do good. “And if a virgin marry, she has not sinned.” Not that virgin who has once for all dedicated herself to the service of God: for, should one of these marry, she will have damnation, because she has made of no account her first faith. But, if our adversary objects that this saying relates to widows, we reply that it applies with still greater force to virgins, since marriage is forbidden even to widows whose previous marriage had been lawful. 1.14. Now again he [Jovinianus] compares monogamy with digamy, and as he had subordinated marriage to virginity, so he makes second marriages inferior to first, and says, 1 Corinthians 7:39-40, A wife is bound for so long time as her husband lives; but if the husband be dead, she is free to be married to whom she will; only in the Lord. But she is happier if she abide as she is, after my judgement …” He allows second marriages, but to such persons as wish for them and are not able to contain; … For as on account of the danger of fornication he allows virgins to marry, and makes that excusable which in itself is not desirable, so to avoid this same fornication, he allows second marriages to widows. For it is better to know a single husband, though he be a second or third, than to have many paramours: that is, it is more tolerable for a woman to prostitute herself to one man than to many. At all events this is so if the Samaritan woman in John’s Gospel who said she had her sixth husband was reproved by the Lord because he was not her husband. For where there are more husbands than one the proper idea of a husband, who is a single person, is destroyed. At the beginning one rib was turned into one wife. And they two, he says, shall be one flesh: not three, or four; otherwise, how can they be any longer two, if they are several.