Preparing a Scientific Manuscript

advertisement

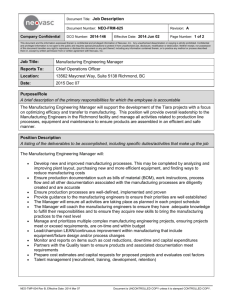

Preparing a scientific manuscript Philip Greenland, MD Senior Editor, JAMA (current) Editor-in-Chief, Archives of Internal Medicine (past) With Thanks to: Fred Rivara, MD; Editor-in-Chief, JAMA Pediatrics; and to Howard Bauchner, MD, Editor-in-Chief, JAMA and The JAMA Network Structure of an Article • Abstract • Introduction 2-3 paragraphs Brief 300-400 words (Not more than 15 references) The frame for your study Be clear what the question is – and why important • Methods 3-5 paragraphs Explain in English and justify use of unusual statistics • Results 5 paragraphs 1st paragraph describe the sample Text should not duplicate tables/figures • Discussion (structured) Principal findings Strengths and limitations Strengths and Limitations vis a vis other studies Meaning of study Unanswered questions/future research • References – landmark papers and most recent publications How do you start? • Begin with an outline • Have others review your outline • Make sure it is clear what your question is • Outline should not exceed 2 pages Outlines USING AN OUTLINE TO PREPARE YOUR PAPER What is an outline? A logical, general description A schematic summary An organizational pattern A visual and conceptual design of your writing An outline reflects logical thinking and clear classification Why make an Outline? Value of the Outline • Aids in the process of writing • Helps you organize your ideas • Provides a snapshot of each section of the paper will flow • Presents your material in a logical form • Shows the relationships among ideas in your writing • Constructs an ordered overview of your writing • Defines boundaries and groups Why make an Outline? Easiest way to share your “paper” with others before you spend a lot of time writing the paper. Developing the Outline - 1 Before you begin: Determine the purpose of your paper Determine the audience you are writing for Develop the thesis of your paper Developing the Outline - 2 Then: • • • • • • • • • Brainstorm: List all the ideas that you want to include in your paper Summarize the question(s)/problem(s) List the key points/elements pertaining to the question(s)/problem(s) Organize: Group related ideas together; place each key point/element in a separate file Order: Arrange material in subsections from general to specific or from abstract to concrete Make sure the organizing scheme is clear and well-structured Identify the important details that contribute to each key point/element Label: Create main and sub headings (IMRAD) Note the sources pertaining to each detail A Good Abstract 90% of readers read ONLY the abstract Structured Concise (300-400 words, 10,000 characters) Keep odd abbreviations to a minimum Show some data Accuracy of data Beware of dataless abstracts Conclusions © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 9 Importance: More than 80% of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF), the most common form of heart failure among older persons, are overweight or obese. Exercise intolerance is the primary symptom of chronic HFPEF and a major determinant of reduced quality of life (QOL). Objective: To determine whether caloric restriction (diet) or aerobic exercise training (exercise) improves exercise capacity and QOL in obese older patients with HFPEF. Design, Setting, and Participants: Randomized, attention-controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial conducted from February 2009 through November 2014 in an urban academic medical center. Of 577 initially screened participants, 100 older obese participants (mean [SD]: age, 67 years [5]; body mass index, 39.3 [5.6]) with chronic, stable HFPEF were enrolled (366 excluded by inclusion and exclusion criteria, 31 for other reasons, and 80 declined participation). Interventions: Twenty weeks of diet, exercise, or both; attention control consisted of telephone calls every 2 weeks. • Slide 10 Main Outcomes and Measures: Exercise capacity measured as peak oxygen consumption (V̇ o2, mL/kg/min; co–primary outcome) and QOL measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF) Questionnaire (score range: 0–105, higher scores indicate worse heart failure–related QOL; co–primary outcome). Results: Of the 100 enrolled participants, 26 participants were randomized to exercise; 24 to diet; 25 to exercise + diet; 25 to control. Of these, 92 participants completed the trial. Exercise attendance was 84% (SD, 14%) and diet adherence was 99% (SD, 1%). By main effects analysis, peak V̇ o2 was increased significantly by both interventions: exercise, 1.2 mL/kg body mass/min (95% CI, 0.7 to 1.7), P < .001; diet, 1.3 mL/kg body mass/min (95% CI, 0.8 to 1.8), P < .001. The combination of exercise + diet was additive (complementary) for peak V̇ o2 (joint effect, 2.5 mL/kg/min). There was no statistically significant change in MLHF total score with exercise and with diet (main effect: exercise, −1 unit [95% CI, −8 to 5], P = .70; diet, −6 units [95% CI, −12 to 1], P = .08). The change in peak V̇ o2 was positively correlated with the change in percent lean body mass (r = 0.32; P = .003) and the change in thigh muscle:intermuscular fat ratio (r = 0.27; P = .02). There were no studyrelated serious adverse events. Body weight decreased by 7% (7 kg [SD, 1]) in the diet group, 3% (4 kg [SD, 1]) in the exercise group, 10% (11 kg [SD, 1] in the exercise + diet group, and 1% (1 kg [SD, 1]) in the control group. Conclusions and Relevance: Among obese older patients with clinically stable HFPEF, caloric restriction or aerobic exercise training increased peak V̇ o2, and the effects may be additive. Neither intervention had a significant effect on quality of life as measured by the MLHF Questionnaire. • Slide 11 Dataless Abstracts Results: Mixed-modeling analyses were used to examine differences in the rate of weight gain over time based on the extent to which children exhibited the ability to self-regulate in the behavioral procedures. Compared with children who showed high self-regulation in both behavioral protocols at ages 3 and 5 years, children who exhibited a compromised ability to self-regulate had the highest BMI z scores at each point and the most rapid gains in BMI z scores over the 9-year period. Effects of pubertal status were also noted for girls. © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 12 Dataless Abstracts Results: Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that increased sugarsweetened beverage intake was independently associated with increased HOMAIR, systolic blood pressure, waist circumference, and body mass index percentile for age and sex and decreased HDL cholesterol concentrations; alternatively, increased physical activity levels were independently associated with decreased HOMA-IR, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations, and triglyceride concentrations and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. Furthermore, low sugar-sweetened beverage intake and high physical activity levels appear to modify each others' effects of decreasing HOMA-IR and triglyceride concentrations and increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 13 A Good Introduction •Short •Focused •10-15 references •Can almost always be 25% shorter •Avoid criticizing others •Be explicit about your question and the GAP that it fills © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 14 Good Introduction – This one is 195 words The use of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) reduces both low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with and those without cardiovascular disease.(1-4) Intensive statin therapy, as compared with moderate-dose statin therapy, incrementally lowers LDL cholesterol levels and rates of nonfatal cardiovascular events.(5-9) Because of the residual risk of recurrent cardiovascular events and safety concerns associated with high-dose statin therapy,(10) additional lipid-modifying therapies have been sought.(11-14) Ezetimibe targets the Niemann–Pick C1–like 1 (NPC1L1) protein, thereby reducing absorption of cholesterol from the intestine.(15,16) When added to statins, ezetimibe reduces LDL cholesterol levels by an additional 23 to 24%, on average.(17,18) Polymorphisms affecting NPC1L1 are associated with both lower levels of LDL cholesterol and a lower risk of cardiovascular events.(19) Whether further lowering of LDL cholesterol levels achieved with the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy leads to a benefit in clinical outcomes is unknown. The Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) evaluated the effect of ezetimibe combined with simvastatin, as compared with that of simvastatin alone, in stable patients who had had an acute coronary syndrome and whose LDL cholesterol values were within guideline recommendations.(20-24) © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 15 Introduction • It is not enough to say: We report here our experience with our first 50 (100, 500, 1000) patients with disease or condition X,Y, or Z. • Why do you feel your experience is worth reporting? • Relate it to some NEED that the reader will have. Even if you identify a gap in the literature, you need to make some statement that indicates that you are “addressing” this gap. Are there conflicting data? Has the problem not been studied in a certain sub-group of people? If you address a subgroup, need to ask yourself if this will be of interest to the audience of the journal that you choose. Major Theme of Paper What are your 2-3 important points (that is remembered) Emphasize in results section of the abstract Conclusion of the abstract should reflect these points Highlight in results section of paper Emphasize in tables Highlight in first paragraph of conclusion © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 17 What Do Reviewers Assess Importance Clarity Design and analysis Should review abstract, text, tables, figures, references, acknowledgements/support Make recommendation to editor Opinions of reviewers are not binding Usually provide comments to authors and separate comments to editors © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 18 Editors Review paper Review comments from peer-review May request statistical help Make recommendation to and participate in manuscript review meeting Accept; accept with revision; reject with revision; reject; short report; research letter Discussed vis a vis importance and validity © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 19 Responding to Reviews Answer completely, answer politely, answer with evidence Most times the reviewer/editor are correct Reviewers provided conflicting suggestions - ask editor You do not have to respond to every issue, but must articulate why not Follow directions – i.e. number responses, indicate changes in manuscript and where they can be found Long explanations to editor in cover letter is not the same as modifying the text © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 20 Polite Responses • • • • • • We agree with the referee that ---- but… The referee is right to point out ---- yet… Although we agree with the referee that… We, too were disappointed by the low response rate. We support the referee’s assertion that ---, although… With all due respect to the reviewer, we believe that this point is not correct. Data not words are a better response © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 21 Responding to Reviews Dear Dr. Moyer, We are pleased to resubmit the revision of our A/R - Manuscript 2010-3686, Management of Children with Sickle Cell Disease: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence” for Pediatrics. We appreciate the valuable and detailed comments provided by the reviewers. In addition to the point-by-point responses, we have provided our responses to the items from the editors below. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have additional suggestions on improving the paper. Thank you. I. Response to Editors: 1) Your revised paper should not exceed 2700 words (excluding the abstract, acknowledgments, references, tables, figures, and appendices). Response: The word count of this revised manuscript is 2699 words. Minor edits were made throughout this manuscript in order to address the reviewers’ comments. 2) Your main title in the Scholar One title box (see above) is different from your main title on the manuscript itself. They should be the same. Response: We apologize for this confusion. The title in the Title Box now matches the title on the Manuscript, “Management of Children with Sickle Cell Disease: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence.” © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 22 Prepare for possible rejection: Even the best work can be misunderstood or underappreciated… © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 23 Dear God: Thank you for submitting your paper about “Creating Life.” Your paper was reviewed by external editors and the consensus is that it will not be acceptable in its present form. We were quite concerned about your methodology. The main issue raised by the Reviewers were: - How do we know Life would not have happened without you. You need better controls. The fact that you did it a few billion times since then does not matter. It was not randomized and might be subject to selection bias. Finally, we need more outcome data about your creation. What is Life supposed to achieve? Please resubmit addressing all the reviewers concerns point by point. Given the extensive changes required, your paper will be treated as a new submission. We look forward to seeing more high impact research from you. © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 24 Authorship – ICMJE Requirements • Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND • Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND • Final approval of the version to be published; AND • Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 25 Spin and Boasting • Exaggeration of Importance “has reached alarming proportion,” drastic increase” • Unfairly disparaging previous research “crisis of credibility, ”methodologic flaws” • Using words to convince, not illuminate “these analyses provide clear answers," the robust association” • Boasting “findings open new frontiers,” “strong new evidence” © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 26 Common Mistakes • Circulating a draft before discussing authorship • Rushing the abstract at the end • Poorly referenced paper • Spelling errors in text and references • Data in abstract that are not in the paper • Data in abstract that are different from the paper • Bait and switch – emphasizing secondary rather than primary outcomes © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 27 Keys to Success Clarity (abstract) Brevity (2500 words) Novelty (why this journal) Modesty (some) Read the journal (often) © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 28 Getting Articles Published Revise and revise – 10 drafts Senior colleagues are critical Never send paper out without internal review first © 2014 American Medical Association Confidential and Privileged • Slide 29 How to Choose a Journal for Submission •No fool-proof method •No standard approach •Discuss what people have used in the past •JANE – journal finder tool