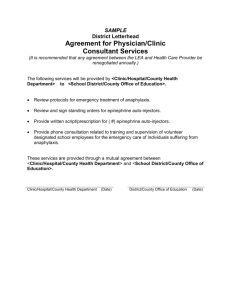

presentation ( format)

advertisement

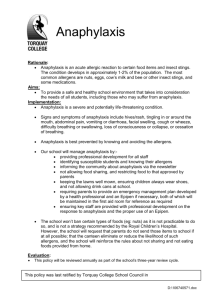

Making Changes to Avoid Repeat Errors: How Cognitive Psychology Can Help Us Eleanor W Davidson MD Sara H Lee MD Our backgrounds Sara Lee Pediatrics, Adolescent Medicine Faculty, Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital Nell Davidson Internal Medicine Clinical Faculty, Department of Medicine The event that led to this presentation 18 year old first year student has flavored coffee & fruit at campus food outlet Symptoms at emergency room included difficulty breathing, wheezing, facial swelling History of anaphylaxis at age 12, “aviary pavilion” Has epipen but not with her Also an anxiety disorder No information on day of event (Monday) Wed: nurse director receives phone call from mother of student. President of university also receives complaint from mother. President puts together a team to analyze what happened & respond Incident Report: Essential elements 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Executive summary Background Initial analysis Investigative procedures Finding(s) Recommendations Staff member performing investigation Executive summary Overview of the incident Estimate risk level (high, medium, low) Determine if risk has been contained Once these steps have been completed, you can continue with root cause analysis of the event. Root cause analysis An opportunity to involve your whole team in a Critical Safety Analysis process: From “Failure Mode Effect Analysis” in the US Military This also derives from a presentation by Edward J Dunn MD MPH and Craig Renner MPH (VA National Center for Patient Safety) Root cause analysis • • • • • A tool in the systems approach to prevention NOT punishment Helps build a culture of safety A process for identifying contributing causes A process for identifying what can be done to prevent recurrences • A process for measuring and tracking outcomes When is RCA done? For any adverse event or close call. For all JCAHO designated “sentinel events” Root cause analysis What happened? (event or close call) • What happened that day? • What usually happens? (norms) • What should have happened? (policies) Root cause analysis Why did it happen? What are we going to do to prevent it from happening again? Actions, outcomes How will we know that our actions improved patient safety? Measures, tracking Similar to the foundations of current “best practice” CME: 1. Identify the “practice gap” (difference between current practice and idealized/achievable practice). 2. Identify what factors are at work, causing that gap. 3. Devise strategies to eliminate the practice gap Strategies Strategies are: 1. Actions we take to prevent the error from happening again. 2. Actions that include outcome measures so we can test their effectiveness. “Hoping for the best” and “trying harder” are not strategies. Testing the action steps 1. Create action with measurable outcomes 2. Test in PDSA cycles 3. Evaluate whether change caused improvement (or simply change) 4. Create additional action steps to test PDSA Cycles Our initial analysis What happened that day? What usually happens? What should have happened? Initial questions Did clinicians not recognize anaphylaxis? Did they recognize it but were hesitant to treat: Unsure about dose of epinephrine? Unsure about safety of epinephrine? Unsure if beginning treatment meant you had to keep patient there? Do pediatricians have different experience-base than internists? How does that affect treatment choices? Do we train clinicians well enough in “urgent care?” Anaphylaxis in Adolescents and Young Adults Anaphylaxis Acute allergic reaction involving 2 or more organ systems or hypotension alone “. . . potentially life-threatening event that requires vigilance on the part of the healthcare practitioner who needs to recognize the condition quickly and initiate early treatment” (Linton E, Watson D. Recognition, assessment and management of anaphylaxis. Nurs Stand. 2010 Jul 21-27;24(46):35-9.) Exaggerated response to an allergen What causes anaphylaxis? 3% of teenagers have food allergies (may be as high as 4-8%), and Number is increasing Anaphylaxis may also be increasing – Pediatric ED visits for food-induced anaphylaxis doubled from 2001 to 2006 in one study Usually triggered by food, insect stings, or medications IgE mediated or other immunologic mechanisms How does anaphylaxis present? • General Anxiety, weakness, malaise • Respiratory Wheezing, difficulty breathing, throat constriction, stridor • Dermatologic Eye redness, lid swelling Swelling of tongue and lips Rash, itching, flushing • Gastrointestinal Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps • Cardiovascular Tachycardia, hypotension • Neurologic Headache, dizziness, confusion Clinical Criteria for Diagnosing Anaphylaxis Adapted from Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report – Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network Symposium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:373-80. Why does anaphylaxis get missed? Anaphylaxis is under-recognized Clinicians may miss anaphylaxis for a number of reasons No exposure to typical offending agent Varied and atypical features No lab tests Differential includes anxiety, vocal cord dysfunction, vasovagal reaction, panic attacks Is anaphylaxis in college students more likely to be missed? Adolescents and young adults appear to be at increased risk for fatal food allergic reactions Less parental oversight Increased risk-taking College students Are unaware of the symptoms of anaphylaxis Have low reported maintenance of any emergency medication Do not tell close campus contacts, campus health services, or dining services Willingly ingest self-identified food allergen (particularly those who have not experienced anaphylactic symptoms) Management of anaphylaxis Assessment Airway – speaking sentences, stridor, wheezing Breathing – RR, work of breathing Circulation – P, BP, cap refill Disability – consciousness Exposure – rashes Management of anaphylaxis Administer IM epinephrine every 5 to 15 minutes until appropriate response is achieved using: *Commercial autoinjector* 0.3 mg for patients who weigh more than 66 lb 0.15 mg for patients who weigh less than 66 lb Or Vial 0.01 mg per kg with a maximal dose 0.5 mg in adults Call 911 or Rescue Squad www.immunize.org Epinephrine is essential Alpha-1 adrenergic agonist vasoconstrictor effects prevent and relieve laryngeal edema, hypotension, and shock Delayed epinephrine is associated with increased risk of fatal reaction Epinephrine is essential – but providers and patients do not use it Epinephrine is used infrequently in emergency settings Despite universal recommendations for the use of epinephrine in anaphylaxis, it is uncommonly used by patients and providers Symptoms perceived as not severe enough Perceived as dangerous Epinephrine effects Expected: Anxiety, headache, dizziness, palpitations, pallor, tremor Rare: Arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, intracranial hemorrhage There are no absolute contraindications to epinephrine in anaphylaxis Perceptions of epinephrine safety – does it vary by specialty training? Pediatricians need to use epinephrine for airway and breathing Internists and Family Medicine physicians need to worry about the effect of epinephrine on the heart Heart is a target organ during anaphylaxis Risk of death from anaphylaxis outweighs other concerns Additional problems How do clinicians conceptualize their job? Whose responsibility is it to manage the unscheduled person who walks into your Health Service? What happens at times when fewer staff are on duty or newer staff only? What are the predictable times when errors with occur? Do you have other thoughts? Transportation? Would patient education help? Would parent education help? I was still puzzled. Lessons from cognitive psychology Cognitive psychology is the science that examines how people: • reason • formulate judgments • make decisions Donald Redelmeier MD The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Annals of Intern Med 2005; 142: 115-120 Why is it a science? The term “science” implies that cognitive errors may be predictable in some situations—not the result of ignorance or the acts of a few bad performers. Can we use this science to improve our practice? - understand how errors are made - take corrective action to avoid them - become more aware of the errors we make all the time, based on incorrect assumptions The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us (Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons) We all believe that we are capable of seeing what’s in front of us: -accurately remembering important events from our past, - understanding the limits of our knowledge, - properly determining cause and effect. But these intuitive beliefs are often mistaken ones that mask critically important limitations on our cognitive abilities. Examples The nuclear submarine and the fishing boat • what the captain thought he’d see when he looked; • we’re only aware of a small portion of our visual world at any moment • we can look, but not see Ben Roethlisberger and the left turn: • Car drivers don’t see the motorcycle because they’re not looking for them—motorcycles are unexpected (they assume they will notice, however) • Raising awareness with signs won’t help, except for short periods of time (cf CME) • Wearing conspicuous clothing? When something is unexpected, distinctiveness does not guarantee that we will notice it (won’t override our expectations) What might help? Make it look more like something expected Make the event less “unexpected” (annual reviews/drills) (Bike riding is safer in cities where it is more common) Cell phones “Most people believe that as long as their eyes are on the road and their hands are on the wheel, they will see and react appropriately to any contingency.” But…”experimental and epidemiological studies show that the driving impairments caused by talking on a cell phone are comparable to the effects of driving while legally intoxicated.” The problem is not that that there are limits on attention; the problem is our mistaken beliefs about our attention. “Even when we know how our beliefs and intuitions are flawed, they remain stubbornly resistant to change.” Not a problem with our eyes or hands. A problem with “consuming a limited cognitive resource” What would it mean to behave as though our attention is not boundless? What strategies do you employ to focus the attention of your staff at work? References Arnold JJ, Williams PM. Anaphylaxis: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Nov 15;84(10):1111-8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky, J, eds. 12th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation, 2011. Greenhawt MJ, Singer AM, Baptist AP. Food allergy and food allergy attitudes among college students. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009 Aug;124(2):323-7. Keet C. Recognition and management of food-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011 Apr;58(2):377-88. Lack G. Clinical practice. Food allergy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 18;359(12):1252-60. Linton E, Watson D. Recognition, assessment and management of anaphylaxis. Nurs Stand. 2010 Jul 21-27;24(46):35-9. Rudders SA, Banerji A, Vassallo MF, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in pediatric emergency department visits for food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Aug;126(2):385-8. Sampson MA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sicherer SH. Risk-taking and coping strategies of adolescents and young adults with food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jun;117(6):1440-5. Additional Resources Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network’s College Network (www.faancollegenetwork.org) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (www.niaid.nih.gov) www.theinvisiblegorilla.com www.beingwrongbook.com