The effectiveness of Social Protection in fighting unemployment

advertisement

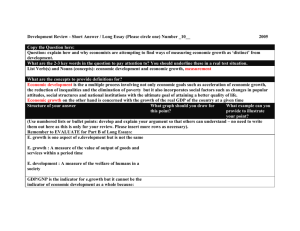

Effectiveness of SP in Fighting Poverty and Inequality Prof Alex van den Heever Chair in the Field of Social Security Alex.vandenheever@wits.ac.za SOCIAL SECURITY IS THE ROUTE TO A HEALTHY SOCIETY Market-related work/employm ent Observed GDP Unremunerated work Leisure Unobserved GDP Total Welfare Subsistence work Market-related work/employm ent Observed GDP Unremunerated work Leisure Unobserved GDP Total Welfare Subsistence work Subsistence work Unremunerated work Leisure Observed GDP Unobserved GDP Total Welfare Market-related work/employm ent Observed GDP Unremunerated work Leisure Unobserved GDP Total Welfare Market-related work/employm ent Cumulative share of income Lorenz curve Structural increase in social risks Structural decrease in social risks Cumulative share of population Impacts on • • • • • Structure of consumption Industrial development Distribution of human capabilities Distribution of welfare/wellbeing Political stability Under normal circumstances the quality of overall social wellbeing is a policy choice and not a function of factors outside the control of governments Social protection seeks to maximise welfare… • No trade-off between well-designed social protection and employment/GDP growth – SP protects the distribution of income – SP protect the distribution of capabilities • Inequality will increase structurally in the absence of social protection • Economic development will proceed more normally if overall welfare is seen as integral to the growth process The distribution of income does not reflect the distribution of capabilities/contribution to output Social Protection Floor • Universal system – Non-contributory (transfers and in-kind services) • Requires income transfers • Subject to progressive realisation – Contributory (social insurance) • Requires well governed mechanisms • Focus on risk pooling • Limited income transfer required • Protection applies to families with and without adequate incomes South Africa comparison: percentage of total income earned by the top 10% of income earners 60 50 Percentage 40 30 20 0 1913 1915 1917 1919 1921 1923 1925 1927 1929 1931 1933 1935 1937 1939 1941 1943 1945 1947 1949 1951 1953 1955 1957 1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 10 SA Source: Malaysia Korea US Year Sweden Germany UK Australia World top incomes database: http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/ South Africa comparison: percentage of total income earned by the top 5% of income earners 50 45 40 Percentage 35 30 25 20 15 10 0 1913 1915 1917 1919 1921 1923 1925 1927 1929 1931 1933 1935 1937 1939 1941 1943 1945 1947 1949 1951 1953 1955 1957 1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 5 Year SA Source: Malaysia Korea US Sweden Germany UK Australia World top incomes database: http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/ (adjusted) South Africa comparison: percentage of total income earned by the top 1% of income earners 30.0 25.0 Percentage 20.0 15.0 10.0 0.0 1913 1915 1917 1919 1921 1923 1925 1927 1929 1931 1933 1935 1937 1939 1941 1943 1945 1947 1949 1951 1953 1955 1957 1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 5.0 Year SA Source: Malaysia Korea US Sweden Germany UK Australia World top incomes database: http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/ (adjusted) Loss of employment Disability Healthcare Pensions Basic family incomes Noncontributory Pensions Social security Contributory Disability Healthcare Loss of employment Welfare services Early childhood development Capabilities Education Policy framework Labour market Active labour market policy Conditions of service determination policy Training and skills development Industrial policy Tax regime Economy Economic growth Regulatory governance Special employment programmes END