Chapter 8 Hominid Origins

advertisement

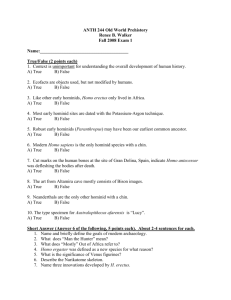

Hominid Origins in Africa Chapter 11 Bipedalism Human os coxae Ossa coxae (a) Homo sapiens. (b) Early hominid (Australopithecus) from South Africa. (c) Great ape. Muscles That Extend the Hip The attachment surface of the gluteus maximus in humans (a) is farther in back of the hip joint than in a chimpanzee standing bipedally. (b) In chimpanzees, the hamstrings are farther in back of the knee. The spine has two distinctive curves—a backward (thoracic) one and a forward (lumbar) one—that keep the trunk (and weight) centered above the pelvis. The pelvis is shaped more in the form of a basin to support internal organs; moreover, the ossa coxae are shorter and broader, thus stabilizing weight transmission. Position of the Foramen Magnum (a) human (b) chimpanzee Major Features of Hominid Bipedalism Lower limbs are elongated, as shown by the proportional lengths of various body segments (e.g., in humans the thigh comprises 20% of body height, while in gorillas it comprises only 11%). The femur is angled inward, keeping the legs more directly under the body; modified knee anatomy also permits full extension of this joint. The big toe is enlarged and brought in line with the other toes; in addition, a distinctive longitudinal arch forms, helping absorb shock and adding propulsive spring. Early African Hominids Three major groups: ◦ Pre-australopiths— the earliest and most primitive hominids (7–4.4 mya) ◦ Australopiths—diverse forms, some more primitive, others highly derived (4.2–1 mya) ◦ Early Homo—the first members of our genus (2.4–1.4 mya) Early Hominid Fossil Finds and Localities Key Very Early Fossil Hominid Discoveries (pre-Australopithecus) Earliest hominids from Africa Central Africa ◦ Sahelanthropus tchadensis East Africa ◦ Orrorin tugenensis Aramis (Ethiopia) ◦ Ardipithecus ramidus Pre-Australopiths (7.0–4.4 mya) A cranium of Sahelanthropus from Chad, dating to 7 mya. The braincase is massively built, with browridges, a crest on top, and large muscle attachments in the rear. Combined with these features is a smallish vertical face with front teeth unlike an ape’s. Key Pre-Australopith Discoveries Dates Region Hominids Significance 4.4 mya East Africa Ardipithecus Aramis Large collection of fossils, partial skeletons; bipedal, bur- derived 5.2–5.8 mya East Africa Ardipithecus Fragmentary, but probably bipedal Key Pre-Australopith Discoveries Dates ~6.0 mya ~7.0 mya Region East Africa Central Africa Hominids Significance Orrorin Tugenensis First hominid with postcranial Remains Sahelanthropus Tchadensis Oldest hominid; well preserved cranium; very small-brained; likely bipedal Australopithecus/Paranthropus from East Africa Australopithecus - An early hominid genus, known from the Plio-Pleistocene of Africa. Australopithecine - The colloquial name for members of the genus Australopithecus and Paranthropus. Features They are all clearly bipedal They all have relatively small brains They all have large teeth, particularly the back teeth, with thick to very thick enamel on the molars. Earlier More Primitive Australopiths (4.2–3.0 mya) Left lateral view of the teeth of a male patas monkey. Note how the large upper canine shears against the elongated surface of the sectorial lower first premolar. Sectorial Adapted for cutting or shearing; among primates, refers to the compressed (sideto-side) first lower premolar, which functions as a shearing surface with the upper canine. Australopithecus afarensis from Laetoli and Hadar Lucy ◦ A partial hominid skeleton, discovered at Hadar in 1974. ◦ This individual is assigned to Australopithecus afarensis. 60-100 individuals 420 cm3 cranial capacity Infant A. afarensis Skeleton An important new find of a mostly complete infant A. afarensis skeleton was announced in 2006. The discovery was made at the Dikika locale in northeastern Ethiopia, near the Hadar sites. The infant comes from the same geological horizon as Hadar, dating 3.3 mya. The “Black Skull” The “Black Skull” dates to approximately 2.5 mya, is the smallest for any hominid known, and has traits reminiscent of A. afarensis. Along with the primitive traits are a host of derived ones that link it to members of the robust group. Australopithecus and Paranthropus from Olduvai and Lake Turkana Robust vs. gracile species Paranthropus aethiopicus Paranthropus bosei Morphology and Variation of the Robust Australopiths (Paranthropus) Australopithecus africanus Australopithecus africanus adult cranium from Sterkfontein Time Line of Early African Hominids Early Homo Homo habilis A species of early Homo, well known from East Africa but perhaps also found in other regions. Handyman Early Homo Fossil Finds South African Sites The first australopithecine “the missing link” between apes and humans was discovered at a quarry at Tuang. As the number of discoveries accumulated, it became clear that the australopithecines were not simply aberrant apes. The acceptance of the australopithecines as hominids required revision of human evolutionary theory. Discovery of Child’s Skull From Taung The Taung child’s skull, discovered in 1924. There is a fossilized endocast of the brain in back, with the face and lower jaw in front. Raymond Dart Raymond Dart, shown working in his laboratory. Dart published the story of the discovery of the Tuang child’s skull. Key South African Pliocene and Early Pleistocene Hominid Discoveries Swartkrans Dates (m.y.a.) 1.8–1.0 Drimolen 2.0–1.5 Paranthropus robustus Taung 2.5–2.0?? Australopithecus africanus Sterkfontein 2.2? Australopithecus africanus; early Homo?) Site Hominids Paranthropus robustus; early Homo? Geology and dating problems in South Africa Complex features ◦ Fissures, sink holes, caves, breccia No volcanic deposits Steps in Interpreting Homind Evolutionary Events 1. 2. 3. 4. Selecting and surveying sites. Excavating sites and recovering fossil hominids. Designating individual finds with specimen numbers for clear reference. Cleaning, preparing, studying, and describing fossils. Steps in Interpreting Homind Evolutionary Events 5. 6. 7. Comparing with other fossil material—in chronological framework if possible. Comparing fossil variation with known ranges of variation in closely related groups of living primates and analyzing ancestral and derived characteristics. Assigning taxonomic names to fossil material. Estimated Body Weights in PlioPleistocene Hominids Male Female A. Afarensis 45 kg (99 lb) 29 kg (64 lb) A. Africanus 41 kg (90 lb) 30 kg (65 lb) South African “robust” 40 kg (88 lb) 32 kg (70 lb) Estimated Body Weights in Plio-Pleistocene Hominids Male Female East African “robust” 49 kg (108 lb) 34 kg (75 lb) H. Habilis 52 kg (114 lb) 32 kg (70 lb) Estimated Statures in Plio-Pleistocene Hominids Male Female A. Afarensis 151 cm (59 in.) 105 cm (41 in.) A. Africanus 138 cm (54 in.) 115 cm (45 in.) South African “robust” 132 cm (52 in.) 110 cm (43 in.) Estimated Statures in Plio-Pleistocene Hominids Male Female East African “robust” 137 cm (54 in.) 124 cm (49 in.) H. Habilis 157 cm (62 in.) 125 cm (49 in.) Estimated Cranial Capacities in Early Hominids Early Hominids Range (cm3) Average(s) (cm3) Sahelanthropus ~350 Ardipithecus Not known Australopithecus afarensis Not known 420 Later australopiths 410–530 Early members of genus Homo 631 Estimated Cranial Capacities in Early Hominids Contemporary Hominoids Range (cm3) Average(s) (cm3) Sahelanthropus ~350 Ardipithecus Not known Australopithecus afarensis Not known 420 Later australopiths 410–530 Early members of genus Homo 631