Optimality Theory and Pragmatics - Hu

advertisement

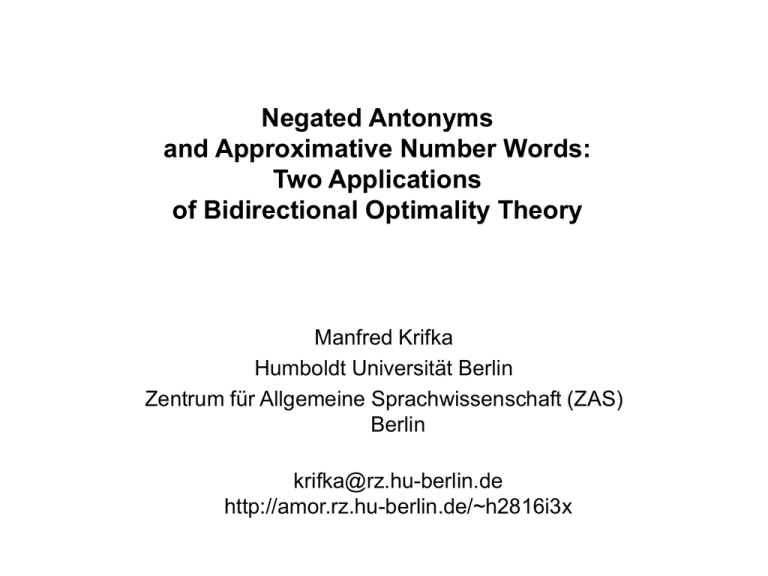

Negated Antonyms and Approximative Number Words: Two Applications of Bidirectional Optimality Theory Manfred Krifka Humboldt Universität Berlin Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS) Berlin krifka@rz.hu-berlin.de http://amor.rz.hu-berlin.de/~h2816i3x Topics of this talk: Two Applications of Bi-OT 1. Interpretation of measure terms with round and non-round numbers, e.g. The distance between Amsterdam and Vienna is one thousand kilometers. The distance is roughly one thousand kilometers. The distance between Amsterdam and Vienna is nine hundred sixty five kilometers. The distance is exactly nine hundred sixty five kilometers. cf. Krifka (2002), ‘Be brief and vague! And how bidirectional optimality theory allows for verbosity and precision’, in D. Restle & D. Zaefferer (eds.), Sounds and systems. Studies in structure and change. A Festschrift for Theo Vennemann, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter) 2. Interpretation of antonyms and their negation, e.g. John is happy. John is not unhappy. John is unhappy. John is not happy. cf. Blutner (2000), ‘Some aspects of optimality in natural language interpretation’, Journal of Semantics 3. Part I: Interpretation of measure terms How much precision is enough? From the land of bankers and watchmakers. Street sign in Kloten, Switzerland. Measure Terms: Round Numbers, Round Interpretations The Round Numbers / Round Interpretation Principle (RN/RI): Round (simple) numbers suggest round (vague or imprecise) interpretations. Krifka (2002) suggests an explanation by general pragmatic principles: 1. A preference for simple expressions (cf. Zipf’s law; Speaker economy; R-Principle of Horn 1984, I-Principle of Levinson 2000) one thousand > nine hundred sixty-five (where a > b: ‘a preferred over b’) 2. A preference for vague, approximate interpretations (cf. P. Duhem 1904, balance between precision an certainty; Ochs Keenan 1976, vagueness helps to save face; reduction of cognitive effort) aprrox. > precise Cognitive motivation: St. Dehaene 1997, The number sense: How the mind creates mathematics distinguishes between an older, approximate sense of numerosity (in animals, babies, many adult uses of number) and a precise sense of counting. Optimal expression-interpretation pairs 3. Interaction of the two principles following Weak Bidirectional OT (Blutner, Jäger): An expression-interpretation pair F, M is optimal iff there are no other optimal pairs F’, M or F’, M’ such that F’, M > F, M or F’, M > F, M. Optimal Non-optimal one hundred, approx. one hundred, precise not competing, cannot be used in same situation, except in cases like one hundred vs. one hundred point zero not competing Non-optimal one hundred and three, approx. one hundred and three, precise Optimal, as the other comparable pairs are non-optimal. Bidirectional Optimization as a general explanationof M-Implicatures Neo-Gricean pragmatics: Horn, Levinson, in particular Levinson (2000), Presumptive Meanings, MIT Press. Three basic principles: Q-Principle (Quantity) Speaker chooses the maximally informative expression of a set of alternative expressions that is still true (provided there is no reason not to do so) Q-Implicatures: John ate seven eggs. ≈≈> ¬ John ate eight eggs. I-Principle (Informativity) Addressee enriches the literal information to a normal, stereotypical interpretation (provided there is no reason not to do so) I-Implicature: Mary turned the switch, and it became dark. ≈≈> temporal order, cause, purpose. M-Principle (Modality / Manner / Markedness) Non-normal, non-stereotypical interpretations are interpreted in non-normal ways, i.e. unmarked expressions ⇔ unmarked interpretations marked expressions ⇔ marked interpretations M-Implicature: Mary turned the switch, and it also became dark. Example: kill vs. cause to die Problem (McCawley, Generative Semantics: kill means cause to die, but: Black Bart killed the sheriff. direct killing Black Bart caused the sheriff to die. indirect killing Explanation by M-implicature: marked (complex) form ⇔ marked meaning Derivation by bidirectional OT: • Form preference: kill > cause to die • Meaning preference: direct killing > indirect killing • Application of evaluation algorithm 〈kill, direct killing〉 〈kill, indirect killing〉 〈cause to die, direct killing〉 〈cause to die, indirect killing〉 A conditional preference for approximate interpretations? Another take on the RN/RI phenomenon: • Assume that precise and approximate interpretation ranked equally, i.e. hearer can expect precise and imprecise interpretation with p = 0.5 • Under approximate interpretation, round numbers are preferred (brevity) shortest expression within range twenty 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 20 thirty-seven 30 40 range of approximate interpret. precise interpretation Rule: Choose least complex number expression within the range of interpretation! If interpretation is precise, there is only one possible number expression. Assume: probability of reported values [0,...100]: 0.01, range of approximate interpretation 4, (cf. error margin) For twenty: probability of use under approximate interpretation = 0.5 * 0.09 = 0.045 probability of use under precise interpretation = 0,5 * 0.01 = 0.005 For thirty-seven: only precise interpretation; under approximate interpretation, forty would be chosen. Conditional preferences for short expressions and vague interpretations Complex constraint rankings: short > long under vague interpretation, i.e. short, approx. > long, approx. approx. > precise for short expressions, i.e. short, approx. > short, precise Optimal Non-optimal one hundred, approx. one hundred, precise. Non-optimal one hundred and three, approx. one hundred and three, precis. Optimal, no other competitor Theoretical Background: Game Theory Game-theoretic approaches to Pragmatics: • Dekker & van Rooy (2000) “Bi-directional optimality theory: An application of game theory”, Journal of Semantics: Optimal form/interpretation pairs are Nash equilibria (local optima); any unilateral deviation from these optima is dispreferred. • Parikh (2001), The Use of Language, CSLI Publ: General game-theoretic approach to communication, “strategic communication” Is preference for short expressions sufficient? Preference for short expressions cannot explain all interpretation preferences: I did the job in twenty-four hours. vague I did the job in twenty-three hours. precise I did the job in twenty-five hours. precise The house was built in twelve months. vague The house was built in eleven months. precise The house was built in thirteen months. precise Two dozen bandits attacked him. vague Twenty-four bandits attacked him. precise ... and sometimes even makes the wrong predictions: Mary waited for forty-five minutes. vague Mary waited for forty minutes. precise I turned one hundred and eighty degrees. vague I turned two hundred degrees. precise Her child is eighteen months. vague Her child is twenty months. precise John owns one hundred sheep. vague John owns ninety sheep. precise Alternative theory: A preference for simple, coarse-grained representations? A preference for coarse-grained representations! Round numbers as cognitive reference points: E. Rosch (1975), Cognitive reference points, Cognitive Psychology Scales of different granularity P. Curtin (1995), Prolegomena to a theory of granularity, U Texas Master Thesis Finer-grained scale of minutes of an hour 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 Application of values Possible durations Application of values 0 15 30 45 60 Coarser-grained scale of minutes of an hour In interpreting a measure report, assume the most coarse-grained scale compatible with the chosen number word! twenty minutes: 20min, assume scale: 5min–10min–15min–20min–25min–... fifteen minutes: 15min, use scale: 15min–30min–45min-60min A preference for coarse-grained representations A priori assumptions: • Assume that durations come with equal frequency within one hour (p = 1/60) • Assume that fine-grained and coarse-grained representations are selected with same probability (p = 1/2) 1. On hearing fifteen minutes, interpreted as 15min: Task of hearer: Find out which scale the speaker used, fine-grained [5...10...15...20min...] or coarse-grained [15...30...45...60min]. a) A-priori probability for fine-grained scale: p = 1/2 Possible values for 15min: (13, 14, 15, 16, 17min): p = 5/60 Total probability of real value + encoding: p = 5/120. b) A-priori probability for coarse-grained scale: p = 1/2 Possible values for 20min: (8, 9, 10, ... 15, ..., 22min): p = 15/60 Total probability of real value + encoing: p = 15/120 Hence assumption of coarse-grained scale (vague interpretation) is safer. 2. On hearing twenty minutes, interpreted as 20min: This term does not exist on the coarse-grained scale, hence fine-grained scale must be assumed (precise interpretation) Bidirectional OT and preference for coarse-grained representations Compare pairs of values (meanings) and levels of granularity of representation Preferred as more probably interpretation, Optimal! 15min, [15-30-45-60min] Not generated! Non-optimal 15min, [5-10-15-20-25min-...] 20min, [15-30-45-60min] 20min, [10-15-20-25min-...] Cannot be true in the same situation, not compared with the other cases -- Optimal! An evolutionary perspective on brevity? It cannot be an accident that for many, perhaps most scales, coarse-grained scales have expressions of reduced complexity (cf. Krifka 2002) Example: Complexity by average number of syllables a. one, two, three, four, ... one hundred: 273/100 = 2.73 b. one, five, ten, fifteen, ... one hundred: 46/20 = 2.3 c. one, ten, twenty, thirty, ... one hundred: 21/10 = 2.1 Suspicion: Scales develop in a way to enable complexity-based optimization, expressions of coarse-grained scales tend to be simpler. An evolutionary perspective on brevity? The optimization of scales. Scales and hierarchies of scales of different granularity have to satisfy certain requirements to be useful for communication: 1. Requirement for scales: Equidistance of units (additive, sometimes logarithmic, cf. decibel; kilo/mega/giga) 2. Requirements for scale hierarchies of different granularity: Scales of increasing granularity Sn Sn+1 Sn+2 should increase granularity by the same factor, [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, ...] [100, 200, 300, 400, 500, ..] [1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, ...]: powers of 10 where the most natural step is decrease granuality by factor 1/2: [1, 2, ...] [1/2, 1, 11/2, 2, ...] [1/4, 1/2, 3/4, 1, ...] cf. hour scale: [1h, 2h, ...], [30min, 1h, 1h30min, ...], [15min, 30min, 45min, 60min, ...] Evidence for preferred reference points: Frequency of number words If fine-grained / coarse-grained scales are used to report measurements, and if with coarse-grained scales, only certain number words occur, then these number words should occur more likely in a natural linguistic corpus containing measurement reports. Cf. Dehaene & Mehler (1992), Cross-linguistic regularities in the frequency of number words, Cognition 43, Jansen & Pollmann (2001), On round numbers: Pragmatic aspects of numerical expressions. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 8, Corpora of English, French, Dutch, Japanese, Kannada: • Between 10 and 100, the powers of ten occur most frequently • Frequency decreases with higher powers of 10, but local maximum for 50 • Between 10 and 20, local maxima at 15, also at 12 (“dozen”) Example: Occurrences of number words in British National Corpus, after H. Hammarström (2004), Properties of lower numerals and their explanation: A reply to Paweł Rutkowski (ms.) 12 15 50 QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Evidence: Frequency of number words Frequency of round numbers on -aine in French French web sites of Google, April 11, 2005, search for strings “une quarantaine de” dixaine 4.230 vingtaine 737.000 onzaine 19 trentaine 866.000 quarantaine 272.000 douzaine 262.000 treizaine 16 cinquantaine 490.000 quatorzaine 47 soixantaine 159.000 540.000 septantaine 614 quinzaine seizaine 6 quatre-vingtaine dix-septaine 1 quatre-vingtdixaine dix-huitaine 11 dix-neuvaine 1 centaine 85 0 548.000 An evolutionary perspective on brevity? The optimization of scales The expressions of values of scales align with the optimization of scales Example: Expression of half points between powers of ten Roman number writing (also motivated iconically, by shape of hand) I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X X XX XXX XL L LX LXX LXXX XC C Simplification of number word ‘five’: English: fifteen (*fiveteen), fifty (*fivety): loss of diphthong, shortening OE fi:f as word vs. fif- as prefix; vowel shift only affected i: (> ai) Colloquial German fuffzehn (fünfzehn), fuffzig (fünfzig): unrounding ü > u, loss of n, shortening (3 morae to 2 morae) Simplification of ‘half’: German anderthalb ‘one and a half’, lit. ‘the second half’ vs. regular eineinhalb Still an effect of complexity of expression? In vigesimal number systems, ‘50’ is more complex than ‘40’/’60’ Question: Is ‘50’ nevertheless used as approximate number word? Conflict cognitive preference / communicative preference Cf. Hammarström (2004), Number bases, frequencies and lengths crosslinguistically. Inspired by that: Investigation of occurrernces of number words on Norwegian vs. Danish web sites of Google (March 4, 2005): Number 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 Norwegian Occurren ces tjue 61300 tretti 43700 fїrt i 39200 femti 81200 seksti 19400 sytti 10200 Њtti 13100 nitti 13500 Danish tyve tredive fyrre halvtreds tres halvfjerds firs halvfems Occurren ces 121000 25400 26800 15500 36400 581 3740 540 Complexity matters: Common belief: Grammars do best what speakers do most (DuBois 1987) But: Sometimes speakers do most what grammars do best! Part II: Antonyms and their Negation Larry Horn (1991), ‘Duplex negatio affirmat: The economy of double negation’; (1992), ‘Economy and redundancy in a dualistic model of natural language’ Basic phenomenon: Mary is not unhappy implicates: Mary is quite happy. Implicature cancelling: She is happy, or at least she is not unhappy. *She is not happy, or at least she is not unhappy. **She is unhappy, or at least she is ot unhappy. Gael Green (1982), Doctor Love: “These days all marriages seem to be doomed”, Barney said.”Who’s happy?” “I’m not unhappy”, Mike offered. Otto Jespersen (1924), The Philosophy of Grammar: “The two negatives [...] do not exactly cancel one another so that the result [not uncommon, not infrequent] is identical with the simple common, frequent: the longer expression is always weaker: “this is not unknown to me” [...] means: ‘I am to some extent aware of it’.“ Parteitag der Bündnisgrünen in M ünster wählt mit großer Harmonie mit Renate Künast und Fritz Kuhn ein neues Führungsgremium umd beschließt die Unterstützung des Atomkonsens der Regierung. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Grüne Harmonie: Glücklich (ganz links): Fraktionschefin Kerstin Müller. Glücklich (darunter): Fraktionschef Rezzo Schlauch. Glücklich (rechts daneben): Gesundheitsministerin Andrea Fischer. Glücklich (darüber): Schleswig-Holsteins Umweltminister Klaus Müller. Glücklich (verdeckt): Umweltminister Jürgen Trittin. Nicht unglücklich (vor Trittin): AußenministerJoschka Fischer. Überglücklich: die neue Parteichefin Renate Künast. (TAZ 26.6.2000) Reasons for being doubly negative: Various proposals in the literature. Psychological exhaustion? Jespersen, ibid.: “The psychological reason for this is that the détour through the two mutually destructive negatives [not uncommon, not unknown] weakens the mental energy of the listener and implies a hesitation which is absent from the blunt, outspoken common or known.” Pomposity? Orwell (1946), ‘Politics and the English language’ “Banal statements are given an appearance of profundity by means of the not un- formation.” Being English? Fowler (1927), A dictionary of modern English usage “The very popularity of the idiom in English is proof enough that there is something it it congenial to the English temperament, & it is pleasant to believe that it owes its success with us to a stubborn national dislike of putting things too strongly”. Completely unnecessary? Frege (1919), ‘Die Verneinung’ “Wrapping up a thought in double negation does not alter its truth value.” Reasons for being doubly negative: Proposals by Horn Horn gives the following taxanomy of motives for saying not un-A a. Quality: S is not sure A holds, or is sure it doesn’t. b. Politeness: S strongly believes A holds, but is too polite, modest, or wary to mention it directly. c. Weight or impressiveness of style: S violates brevity precisely to avoid brevity. d. Absence of a corresponding positive (e.g., not unfounded) e. Parallelism of structure f. Minimization of precessing, in contexts of direct rebuttal or contradiction. Here: Mainly Reason (a). A first pragmatic OT treatment: Blutner 2001 happy and unhappy are contraries; their lexical meanings do not apply to to emotional states in middle range. happy unhappy The literal meaning of the negations not happy and not unhappy: happy unhappy not unhappy not happy Negated forms compete with shorter forms and are pragmatically restricted: happy unhappy not unhappy not happy Problem: -- Unclear how different interpretation of not happy and not unhappy comes about, -- prediction: not unhappy gets blocked because it is more complex than not happy! A Weak Bi-OT Theory about Happiness Assume that antonyms are literally interpreted in an exhaustive way, i.e. they are contradictories. Initial situation: Antonym pairs and their negations. happy unhappy not unhappy not happy I-Implicature: Restriction of simpler expressions to prototypical uses. happy unhappy not unhappy not happy M-Implicatures: Restriction of complex expressions to non-prototypical uses. happy unhappy not unhappy not happy Weak Bidirectional-OT on Being not Unhappy Preference for stereotypical interpretations: > > Preference for simple expressions: happy > unhappy > not happy > not unhappy happy, not unhappy, happy, not unhappy, unhappy, not happy, unhappy, not happy, A reason to prefer extreme interpretations With exhaustive interpretation of antonyms: It is unclear where to draw the border, cf. epistemic theory of vagueness of Timothy Williams (1994). happy happy happy unhappy unhappy unhappy Saying that someone is happy or unhappy may not very informative if the person’s state is close to the borderline; this is a motivation for restricting the use of happy/unhappy to the clear cases, the ones on which speaker and hearer definitely should agree upon. happy unhappy Further phenomena in the interpretation of evaluative adjectives Litotes (understatement): This is not bad for ‘This is good’, I’m not unhappy about it for ‘I’m happy about it’ Avoidance of positive values from the range of expressions. Reason: showing off critical attitude that nothing can be really positive. happy unhappy not unhappy not happy Avoidance of negative values This is not good for ‘This is bad’ I’m not happy about it for ‘I am unhappy about it’ Avoidance of negative values from the range of expressions Reason: Politeness, attempts to save face. happy unhappy not unhappy not happy Conclusion Round numbers / round interpretations: -- Refined theory of interpretation preferences, extending usual forms of bidirectional optimization. -- Simplification of forms a secondary factor after preference for coarse-grained scales with round numbers? -- Development of scales to allow for round numbers / round interpretations Interpretation of antonyms: -- Standard application of bidirectional optimization gets the facts right if we assume basic exhaustive interpretation of antonyms -- Explanation of tendency for stereotypical interpretations in Williamsons’ epistemic theory of vagueness -- Litotes as avoidance of extreme values. krifka@rz.hu-berlin.de http://amor.rz.hu-berlin.de/~h2816i3x