Memory - TeacherWeb

advertisement

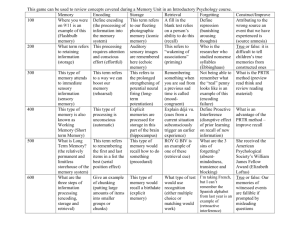

Memory What causes us to remember certain things, but not others? Memory is defined as learning that has persisted over time. It is a fundamental component of our daily lives. We rely on our memories to let us know who we are, what is safe, where we live, etc. Psychologists usually focus on three key questions: 1. How does information get into our memory? (Encoding) 2. How is information maintained in our memory? (Storage) 3. How do we get information back out of our memory? (Retrieval) Encoding is the process of putting information inside of your head. Think of encoding like typing a project on your computer. It involves attention, focusing your awareness on a narrow range of stimuli or events. The next step, storage, involves maintaining the encoded information over a period of time. Storage is like pressing “save” on your computer. Finally, there is retrieval, or getting the information you have stored back out of your head so you can use it. This would be the same as finding and opening the document on your computer. In order for anything to enter out memory, it must first be picked up by our senses. This first stage of memory is called sensory memory, which is defined as a split second holding tank for all sensory information. Most of what our senses detect, we forget almost immediately. Researcher George Sterling demonstrated that sensory memory exists, and that it only lasts a split second. He flashed a grid of nine letters, three rows and three columns, to participants for 1/20 of a second. The participants in the study were directed to recall either the top, middle or bottom row immediately after the grid was flashed to them. His experiment demonstrated that the entire grid must be held in the sensory memory for a split second. This type of sensory memory is called iconic memory. If not asked what the letters in the grid were immediately after the flash, the participants would have no recollection of ANY of the letters. Other experiments demonstrated the existence of echoic memory, an equally split second memory for sounds. Three-Box/Information processing model of Memory Most of the information in or sensory memory is not encoded, however some of it is encoded in the next stage of our memory: short term memory. What determines which sensory messages get encoded? Selective attention: we encode what we are paying attention to or what is important to us. Short-term memory is everything you are thinking of at the current moment. It is also temporary. If you do nothing with them, they usually fade in 10 to 30 seconds. The short-term memory is kind of like a pier or dock. If you put too many people on the dock, someone will fall off into the water. Like the dock, the short-term memory can only fit a certain number of things before some fall off (forget). The average short term memory is around 7 units. For example, we can hold about seven numbers in our short term memory (that is why phone numbers are seven digits long). Now, we can increase our short term memory by chunking information. Chunking is grouping information into larger units. With phone numbers, we usually don’t see the individual numbers. Instead we group and see the individual pieces as one. (Our area code, 985, is usually thought of as “one” number.) Think of the numbers 177618121945these digits may seem really hard to memorize- but if you chunk them into meaningful units (in this case famous dates in US history)- 1776- 18121945- then the task becomes much easier. A popular example of chunking is called mnemonic devices: or memory aids. ROYGBIV (for the colors of the visible light spectrum) or My very excellent mother just served us nine pizzas (for the planets) are examples of mnemonic devices (but I guess Pluto is not a planet- so get rid of pizzas and change nine to nutterbutters and everything is cool). Now the MOST popular way to get information from our short-term memory into the next type of memory (long-term memory) is to rehearse the information. Rehearsing is just repeating the information that you have in your short-term memory enough times so it gets transferred into the long-term memory. Long-term memory (LTM) is our limitless storehouse for information. Now although the LTM is unlimited, memories can decay or fade over time. LTM is broken down into two major types (declarative and nondeclarative) Declarative Memories (also called explicit memories) are our conscious memories that we have to put effort in to remember. There are two tyoes of declarative (explicit) memories. 1. Semantic memory: General knowledge of the world stored as facts. If you remember the names of Columbus's three boats then you have a semantic memory. 2. Episodic memory: Memories of specific events. Think of this like episodes of your life; like remembering your 14th birthday party. Non-declarative Memories (also called implicit memories) are unintentional memories that we might not even realize we have. There are two major types: 1. Procedural memories: Memories of skills and how to perform them. (Riding a bike) 2. Classically conditioning: Anytime you have been classically conditioned, you form a nondeclarative (implicit) memory. When Pavlov's dogs salivated at the sound of the tone- their body remembered the connection between the food and the bell- that was not a conscious memory- thus it is non-declarative. The Levels of Processing Model is just another way of looking at memory. Instead of thinking of memories as long-term of short-term, this model looks at them as how deeply they have been processed. They are deeply (elaborately) processed or shallowly (maintenance) processed. If you repeat something over and over again to yourself, take a quiz on it and do well, but forget it soon after- that information was shallowly (maintenance) processed in memory. If you give the information meaning while memorizing it (for example, relate it to your life or talk about it with friends) then you should deeply (elaborately) process the information and it will last much longer in your memory. Getting the information out of our heads so we can use it is a pretty important part of memory. There are basically two main types of retrieval: recognition and recall. Recognition: is the process of matching a fact or concept with one already in memory. You are given a cue and just have to recognize the right answer. Multiple choice quizzes test your ability to use recognition. Recall: coming up with an answer from your memory. Fill in the blanks test your recall. In most cases, it is easier to retrieve information through recognition, rather than recall. The way information is presented to us greatly affects our retrieval ability. For example, the primacy effect predicts that we are more likely to recall items presented at the beginning of a list. The recency effect is demonstrated by our ability to recall items at the end of a list. Finally, there is the serial positioning effect, which states that when given a list, we are more likely to retrieve the items at the beginning and end of a list and forget the stuff in the middle. Context is an important factor in retrieval. Have you ever tried to remember someone's name but can only recall their appearance and or maybe the first letter of the name? This temporary inability to remember information is sometimes called the tipof-the-tongue phenomenon. One theory that explains why this might work is the semantic network theory. This theory explains that our brain might form new memories by connecting their meaning and context with meanings already in our memory. Thus, our brain creates a web of interconnected memories, each one in context tied to hundreds or thousands of other memories. So by listing traits, you gradually get closer and closer to the name and you are finally able to retrieve it. Context also explains another powerful memory experience we all have. Think about where you were when you heard about 9/11. You can probably tell me where you were and what you were doing. Ask your parents what they were doing when the Challenger exploded, when JFK was shot, or during the OJ white Bronco chase. These flashbulb memories are powerful because the importance of the event caused us to encode the context surrounding the event. The emotional or situational context of a memory can effect retrieval in yet another way. Studies consistently demonstrate the power of mood congruent theory; which is the idea that you are more likely to recall an item if you are in the same mood when you encoded the item. One last way the context effects retrieval is called state dependent memory. This refers to the idea that you will more likely retrieve information if you are in the emotional of physical state that you encoded it. the 1980’s and 1990’s “recovered memories” were big headlines. Individuals claim suddenly to remember events that have been “repressed” for years, often in the process of therapy. Parents have been accused of molesting and even killing children based on these recovered memories. In Sometimes these recovered memories have been corroborated with physical evidence and justice was served. Other times, they have been discovered to have been fabricatedconstructed recollections of events. A constructed memory can report false details of a real event or might even be a recollection of an event that never occurred. It is inevitable, we forget things. Sometimes we forget things because the memories decay, or we do not use the memory or connections to that memory for a long time. (Often before an AP exam if you have not reviewed!) But the good news is that if the memory existed in the first place, relearning the material occurs MUCH more quickly the second time (and even more quickly the third). This is called the relearning effect. Another factor that causes forgetting is interference. Sometimes other information in your memory competes with what you are trying to recall. There are two types of interferences – retroactive and proactive Retroactive interference: Learning new information interferes with the recall of old information. You learn a new locker combination and now cannot remember last years combination. Proactive interference: Older information learned previously interferes with the recall of information learned more recently. You call your new girlfriend/boyfriend your old one's name. How are memories stored in the brain? We know that the hippocampus in the brain is involved in the process of memories. For example, damage to the hippocampus can cause anterograde amnesia in which people cannot encode new memories but remember ones already in their long term memory. Sometimes they can learn new skills, but will never remember having learned them, showing us that procedural memories are not handled by the hippocampus. We use our whole brain for storage. The current theory on how memories are stored on a neural level is called longterm potentiation. Studies show that neurons can strengthen connections between each other. Through repeated firings, the connection is strengthened and the receiving neuron becomes more sensitive to the messages from the sending neuron. It is kind of like using a machete to clear a pathway in a jungle. The first time you chop through it is a slow process. But the more times you chop through that path, it becomes clearer.