W.E.B. Du Bois, The Niagara Movement

advertisement

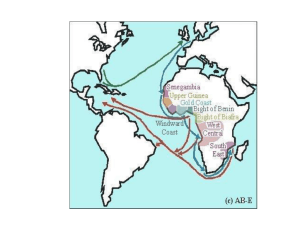

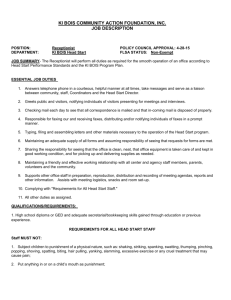

W.E.B. Du Bois, 1868-1963 W.E.B (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois was born on February 23, 1863 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Du Bois knew little of his father. Alfred Du Bois married Mary Burghardt in 1867. Soon after Du Bois was born, his father left, never to return. Du Bois described him as "a dreamer-- romantic, indolent, kind, unreliable, he had in him the making of a poet, an adventurer, or a beloved vagabond, according to the life that closed round him; and that life gave him all too little." Du Bois at the age of four, dressed to conform to the Victorian era's idea of how well-behaved little boys should appear. Du Bois at age nineteen. Jubilee Hall at Fisk University is the oldest permanent building for the higher education of African Americans in the United States Du Bois with Fisk University faculty and students in front of Jubilee Hall, c. 1887. Fisk University Class of 1888. Du Bois at Harvard, 1890, or University of Berlin, 1892. Du Bois was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1896. Du Bois at the Paris International Exposition in 1900 where he won a gold medal for his exhibit on the achievement of black Americans. Du Bois met Nina Gomer while at Wilberforce and they were married in 1896. Their first child, Burghardt, died as an infant in Atlanta from a typhoid epidemic. Du Bois at Atlanta University, 1909. Scene of Lynching at Clanton, Alabama, Aug. 1891 The lynching of Lige Daniels. August 3, 1920, Center, Texas. Du Bois and other black leaders of similar opinions organized what became known as the Niagara Movement. It was the first organization to seek full political and economic rights for Afro-Americans at a national level. By 1910, the organization led to the founding of the NAACP. Du Bois (2nd row, 2nd from right) in a NAACP sponsored demonstration against lynching and mob violence against blacks. Du Bois receiving the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, Atlanta University, 1920. Du Bois and members of The Crisis staff in their New York office. Resolutions established by 15 countries at the first Pan-African Congress, Paris, February 1919. Speakers at the Pan-African Congress held in Brussels, Belgium, in 1921. Du Bois is 2nd from right. Du Bois carried his message to the political arena when he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1951 on the American Labor Party's ticket. Du Bois, with Shirley Graham Du Bois (right) and other indicted members of the Peace Information Center, in Washington prior to their court hearing. Throughout the 1950s, Du Bois' concerns became increasingly international, and he traveled and lectured on a number of issues including disarmament and the future of Africa. Ghana's President Kwame Nkrumah offers a toast on Du Bois' 95th birthday, c. February, 1963. One thing alone I charge you. As you live, believe in Life! Always human beings will live and progress to greater, broader and fuller life. The only possible death is to lose belief in this truth simply because the great end comes slowly, because time is long. -- W.E.B. Du Bois in his last statement to the world, 1963 “How does it feel to be a problem?” W.E.B. Du Bois, 1868-1963 W.E.B. Du Bois, Strivings of the Negro People (1897) Main Points: 1. Being a problem [i.e. being an black person in 19th c. America] is a disturbing experience, compelling one to always take other people’s estimation of them in consideration and creating a doubleconsciousness. [T]he Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,-a world which yields him no self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. (p. 123) 2. The African American feels his duality of being both African and American. One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He does not wish to Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa; he does not wish to bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism, for he believes — foolishly, perhaps, but fervently — that Negro blood has yet a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without losing the opportunity of self-development. (p. 123) 3. The end of the Negro’s striving is “to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, and to husband and use his best powers. (p. 123) 3. Prejudice and discrimination keep the freedman oppressed. The freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of lesser good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people…. (p. 88) 4. Americans, including white Americans, should appreciate the Negro race. Work, culture, and liberty,--all these we need, not singly, but together; for to-day these ideals among the Negro people are gradually coalescing, and finding a higher meaning in the unifying ideal of race,--the ideal of fostering the traits and talents of the Negro, not in opposition to, but in conformity with, the greater ideals of the American republic, in order that some day, on American soil, two world races may give each to each those characteristics which both so sadly lack. (p. 88) W.E.B. Du Bois, The Niagara Movement, (1905) 1. We should meet, despite the existence of other organizations for Negroes. 2. We must complain about common wrongs toward blacks. We must complain. Yes, plain, blunt complaint, ceaseless agitation, unfailing exposure of dishonesty and wrong—this is the ancient, unerring way to liberty, and we must follow it. (p. 100) 3. In not a single instance has the justice of our demands been denied, but then come the excuses. They still press on, they still nurse the dogged hope, — not a hope of nauseating patronage, not a hope of reception into charmed social circles of stock-jobbers, pork-packers, and earlhunters, but the hope of a higher synthesis of civilization and humanity, a true progress, with which the chorus "Peace, good will to men,“ "May make one music as before, But vaster." Pages 126-127. One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He does not wish to Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa; he does not wish to bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism, for he believes — foolishly, perhaps, but fervently — that Negro blood has yet a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without losing the opportunity of self-development. p. 125. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. p. 124. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance, — not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of filth from white whoremongers and adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home. A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. p. 126.