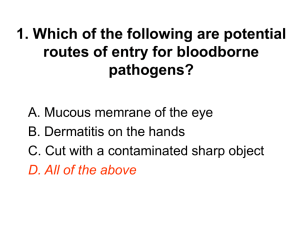

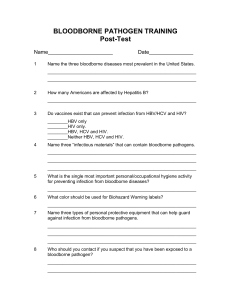

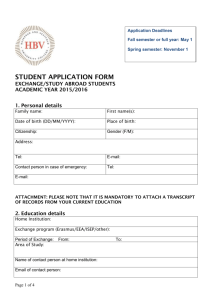

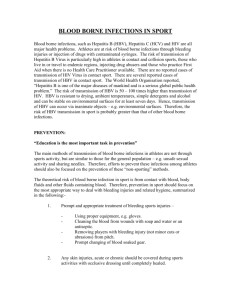

The concepts of hepatitis B and C infections

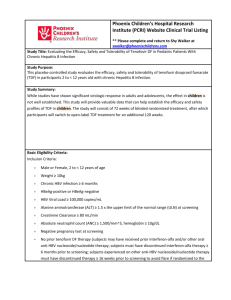

advertisement