A Separate Peace Theme of Identity

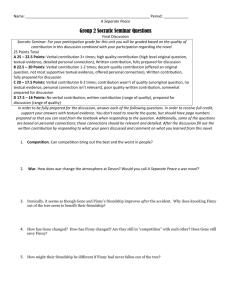

advertisement

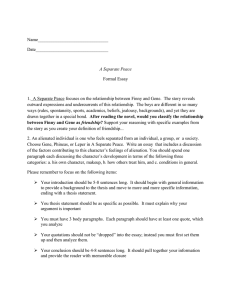

A Separate Peace tells the story of a sixteen-year-old boy at boarding school in New Hampshire during World War II, and the mixed feelings of admiration and jealousy he harbors for his best friend and roommate. (Things get messy pretty fast, as you might expect from a bunch of ill-supervised adolescents.) Published in 1959, the novel is the first from author John Knowles, who would follow his breakout success with many more novels, short stories, and essays, including a sequel of sorts, Peace Breaks Out. Still, nothing ever topped Knowles's debut; A Separate Peace remains his most popular and well-known work. Just ask any of the high school students who have read it in class. Speaking of English class, Knowles seems to have followed that old English teacher's adage: write what you know. Like the main character and narrator of A Separate Peace, Knowles was born in the South (West Virginia) and during World War II attended boarding school in New Hampshire, at Phillips Exeter Academy. His descriptions of the fictional "Devon school" in A Separate Peace are largely based, physically, on the Exeter campus. (Yes, those marble stairs are still there. Yes, they're still very hard.) Even parts of the plot – like the jumping out of the tree gig, or the character of Phineas – came from Knowles's experiences as a student. (So just think: someday you could write a novel that 1) stands as one hallmark of great modern American literature, and 2) embarrasses the heck out of your high school friends.) Why Should I Care? You know all those stories you see on the news about overzealous soccer moms, irate hockey dads, referees that got beat-up, and cheerleaders with not-so-accidentally twisted ankles? Jealousy makes people do crazy things, especially when it comes to athletics. Now, if you've ever competed in ANYTHING, you know that particular feeling well. It's an odd combination of admiration and resentment. One minute you're worshipping at the feet of your hero-of-the-week, and the next you're eyeing a baseball bat with less-than-benevolent intentions. What is it that makes us want to win so badly, even at the most trivial of tasks? You know, like that time you were fingerpainting with the kids from down the street and entire jar of black paint just happened to spill on their Picasso-like rendition of King Kong? Competition is supposed to be healthy, but where do you draw a line between benign rivalry and a referee with a black eye? Fortunately, A Separate Peace helps in this grand debate by establishing quite clearly that knocking your best friend out of a tree is on the wrong side of that line, and you'd best not be crossing into uber-rivalry territory any time soon, lest in the process you lose your sense of personal identity and discover all the atrocities of war and the human condition. A Separate Peace Theme of Friendship A Separate Peace focuses on the friendship between two sixteenyear-old boys, and it's…complicated. Friendship is a combination of admiration, respect, jealousy, and resentment. For all the camaraderie between them, these boys are still driven by good old healthy competition, which at times can end up being, well, less than healthy. Friendship blurs identity, as one boy begins to assimilate the life of the other. You know, Talented Mr. Ripley-style and all. Questions About Friendship 1. Do Phineas and Gene have an equal friendship, or is one boy on top? Does this question change if you're looking at their relationship 1) from Gene's point of view, 2) from Finny's point of view, 3) objectively? (Are those last two even possible in this novel?) 2. When Finny returns to Devon in September, how has his relationship with Gene changed from the summer months? 3. At what moment does Gene betray Finny? ("When he causes his fall from the tree" is not the only answer to this question.) 4. What is the nature of Gene's relationship with Leper? A Separate Peace Theme of Warfare A Separate Peace explores not only military warfare (it takes place during World War II), but personal wars. Feelings of hostility, resentment, and fear dominate even what should be the most peaceful of environments. The novel claims that we all identify enemies in the world around us, that we "pit ourselves" against them so as to have an object for our hate and fear. Wars, both personal and political, are thus "the result of something ignorant in the human heart," an inability to understand the self and others. Questions About Warfare 1. What are the different types of warfare we see in A Separate Peace? Which is the most destructive? 2. Finny doesn't admit the war is real until Leper goes crazy. What's up with that? 3. At the end of the novel, Gene claims that he killed his enemy at Devon. To whom/what is he referring? ("Phineas" is not the only answer to this question.) A Separate Peace Theme of Youth In A Separate Peace, youth exists in its own environment, isolated physically, mentally, and emotionally from the rest of the world. Growing up, then, involves a transition from this sheltered environment to the harsh realities of things like war, hatred, and fear. Yet these realities permeate and destroy the world of youth, particularly given the setting (World War II, which threatens peace even for the young). Questions About Youth 1. Who is more mature, Gene or Finny? Does Gene grow past Phineas after the accident, or does he regress? What does "mature" mean in this novel, anyway? 2. In the beginning of A Separate Peace, it would seem that joining the army represents a transition to the adult world. Does Leper's fate confirm or dispute that theory? 3. Does Phineas's injury push him into the world of adulthood or further into his youthful fantasies? A Separate Peace Theme of Identity A Separate Peace explores the difficulties with understanding the self during adolescence. (When we say it like that, it sounds like buckets of fun, doesn't it?) Identity is complicated enough as the narrator enters adulthood in a time of war, but a difficult friendship with a fellow student and rival leads to a further confusion of identity. Attempting to alter identity serves any number of purposes, from escaping guilt to living through others to dealing with insanity, but these attempts ultimately fail; the characters are forced to deal with their selves, actions, and personal identities. Questions About Identity 1. Gene in many ways assimilates Finny's identity after the accident. Think about the differences between Gene's reasons for doing this, and Finny's reasons for encouraging it. (Yes, you're right, that wasn't a question. But it got you thinking, didn't it?) 2. If these characters are always shifting – like Brinker's big transition from leader to rebel – how is the self defined in A Separate Peace? Is Leper a different person after his military experience, as Gene claims he is? 3. Does narrator Gene have a different identity than sixteen-year-old Gene? A Separate Peace Theme of Rules and Order At first, A Separate Peace presents the classic struggle between young anarchy and old, established rules. This plays out at a boarding school, where the rules indeed seem restrictive and unwarranted. But other systems of rules soon emerge, as even the poster child for adolescent rebellion lives by a set of "commandments." Rules, then, do not always restrict and control. We learn that the best indication of a character is the rules that he lives by and the principles he follows. Questions About Rules and Order 1. What are the different systems of rules and order that we see in A Separate Peace? When do they conflict? Which "wins out" at the end of the day? 2. Gene says of Devon's rules that, when you broke them, they broke you. Is he referring only to Finny's fall? What does he mean? Is that true in the novel? 3. The narrator mentions Finny's "commandments" several times in the novel. Does Gene, too, live by these rules? Do these rules change after Finny's accident? A Separate Peace Theme of Memory and the Past In A Separate Peace, memory is unreliable. It forgets certain events, changes others, misinterprets the truth and presents it as fact anyway. But memory also illuminates, because it…forgets certain events, changes others, and presents skewed reality as fact. The same problems with memory are also its assets, because it tells us what's important, what's not, and a whole truckload of info about whoever's doing the recollecting. Memory illuminates, even through the facts it leaves out. Questions About Memory and the Past 1. Does the narrator still feel guilty about his actions as a sixteen-year-old boy, or has he made his peace with what happened at Devon? 2. The narrator says that everyone has a piece of the past that they use to define reality, and that his is the war. How does this color the way we read his narrative? Why is it that this piece of his life is what has stuck with him? 3. At the end of the novel, Gene says that he lives in Finny's created atmosphere. From his narrative, do you get a sense that this is true? In what way is this relic from the past (his feelings about Phineas) defining his character at the present? A Separate Peace Theme of Jealousy Jealousy is just one of a slew of negative emotions in A Separate Peace, among them fear and resentment. What makes these feelings so difficult is that they're accompanied by admiration, respect, and love – all the ingredients for one very confusing friendship between adolescent boys. We see that jealousy drives people to unthinkable and incomprehensible action, understood least of all by those responsible for it. Questions About Jealousy 1. Gene states in Chapter Three that "Phineas always had a steady and formidable flow of usable energy" (3.40). When this sort of energy is gone – say, long after the accident, when Finny stands with Gene outside the gym, catching his breath and balanced on crutches – does Gene still envy him? 2. Does Gene's jealousy of Phineas abate at any point? When? Why? How do you know? 3. Is jealousy ever constructive in A Separate Peace? A Separate Peace Theme of Fear Fear abounds on multiple levels in A Separate Peace, accompanying the various "wars" fought throughout the course of the novel, wars both military and personal. Adolescent fear of the future stems from fear of the self, as the novel's young men wonder whether they are capable of functioning in a world consumed by war and hatred. We also see fear revolving around personal identity and, most prominently, fear of one's own character, of the crimes of which one may be capable. Questions About Fear 1. What are the different sources of fear for the Gene in A Separate Peace? Which is the most inhibiting for Gene? 2. How is fear different for the sixteen-year-old Gene than it is for the narrator? Where do we see these differences illuminated? Can we trust the narrator in these instances? 3. Does fear spur Gene to action, or hold him back from action? How does it affect his behavior? Sports, Games, and the War Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory A Separate Peace spends a lot of time talking about the war, and as much time talking about sports. At first these seem like completely different things. Sport is, as Finny sees it, "purely good," whereas war is destructive and, as Gene says, caused by "something ignorant in the human heart." Of course, the kicker is that, at least for the boys at Devon, the war holds strange parallels to sport. Their eagerness to enlist suggests a misguided understanding of warfare as the ultimate game. Phineas, the master of all sports, is devastated to discover he can't be part of the fun. Of course, the novel argues that war is purely evil, as opposed to purely good fun and games. Once you start looking, you see the idea of sport cropping up all over the place at Devon, from Finny's purely innocent Blitzball to the rivalry Gene establishes between himself and Finny – a rivalry that proves itself to be deadly. As peace deserts Devon, as the boys move from their youth to adulthood, sports are perverted from their once "purely good" form and take on warlike traits. No better example exists than Leper's obsession with skiing. Once a solitary and reflective afternoon activity, skiing is taken over and made into an instrument of war. There's also the idea of the Olympics; Finny tries to use sport to compensate for not being able to participate in war. And don't forget the tree incident itself – a devastating, warlike perversion of what was once purely good, treejumping sport. Finny's Broken Leg Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory OK, read this exchange between Phineas and Gene: "Isn't the bone supposed to be stronger when it grows together over a place where it's been broken once?" "Yes, I think it is." "I think so too. In fact I think I can feel it getting stronger" (11.15-7). As you might have guessed, they're not just talking about the bone. They're talking about their friendship. The everoptimistic Phineas believes that, having suffered a break in their relationship (betrayal, suspicion, confession), the boys have patched things up (forgiveness) and their friendship is now stronger than ever. This is…dubious, to say the least. Finny's leg is much weaker now than it was before, as demonstrated in a few chapters by fall #2. So we have to ask whether the same is true of their friendship, if it, too, is weakened by the break. What do you think? The Winter Carnival Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory OK, by now you've probably heard us talk on and on about the two sessions at Devon, Summer and Winter, and how they represent, respectively, youth/innocence/peace/rebellion and rules/authority/war/adulthood. If this is true, then even the name "Winter Carnival" is in itself oxymoronic (contradictory). How can you have a carnival of games during the somber, rule-driven Winter Session? Phineas, that's how. When Finny, the spirit of the Summer Session, returns to Devon in the Winter, crippled, he is pitted against the rules and authority of this rather serious time. Of course, Finny has no enemies, so he doesn't see it that way. "I love the winter," he says, and adds that it loves him back. The carnival is, then, a victory for Phineas, proof that the "atmosphere" he "creates" can prevail in a time of war. At least, this WOULD be the conclusion, had the Winter Carnival not ended with the arrival of a telegram from Leper, having been driven mad by the war, the very event that will pull Phineas out of his world of fantasy and back into wartime reality. A Separate Peace Setting Where It All Goes Down The fictional Devon school in rural New Hampshire, 1942-3 The setting of A Separate Peace – both time and place – are integral to the story and its meaning. As you'll read, well, everywhere in this guide, the backdrop of World War II establishes a series of parallels with the daily lives of the boys at Devon. "War" is both a military and personal term. (Gene fights a war against his own jealousy and fear, he identifies Finny as the enemy, and the boys all struggle against their personal demons.) As far as place is concerned, Devon is presented as an almost Edenic paradise. (Edenic = Eden-like. Get used to it, you'll see this word a lot in literary criticism.) The trees, the animals, the peaceful, lazy rivers – you get the picture. Notice how the war slowly creeps into the academy, starting with recruiters and ending with troops in Chapter Thirteen? Devon's initial isolation from the rest of the world is as important as its peaceful atmosphere. The boys are physically sequestered from adults and from war, but this barrier is an impermanent one. What’s Up With the Ending? At the end of the novel, Gene concludes that what made Phineas different was his lack of resentment, lack of fear. Everyone, he claims, identifies an enemy in the world and pits themselves against it. Everyone that is, except for Phineas. Great, but the guy's dead. So it doesn't look like his viewpoint did him much good in the world, does it? Let's backtrack a moment to Gene's final conversation with Finny, in the Infirmary before his surgery. Gene tells Finny that he wouldn't be any good in the war. He's too kind, too playful, too naïve to genuinely fight any real enemy. To Finny, it would just be sport, and sports are always good, and everyone always wins. But Gene isn't just talking about the war. (They never are, in this novel.) He's talking about the adult world from which the boys at Devon are isolated and which they will all need to enter, eventually. Finny isn't just ill-equipped for the war, he's ill-equipped for reality. In a way, then, Phineas needed to die for the story to reach its logical conclusion. Men like Finny don't exist in the world; they can't, because they're simply too good for it. Few relationships at Devon aren't based on rivalry, Gene tells us, which is why he's so disturbed when Finny removes himself from competition. Finny, with his fantasies and naiveté, is on a higher, separate plane from the rest of us. Either he will be corrupted by the world, or destroyed by it, and in this novel, it's the latter. So, back to that ending. Gene's explanation of Finny as an exception to the rest of us is expected; but that last line of the novel isn't. Gene turns the tables, switches his focus from the exception to the norm, which he questions: "...if he was indeed the enemy." Maybe, he ventures, Phineas's outlook was the better one. Maybe enemies are fictional, enmity a mere self-infliction. Either way, the adult Gene is still questioning and trying to learn, which is an optimistic response to his Chapter One hope that he would someday achieve growth and harmony.