School Readiness

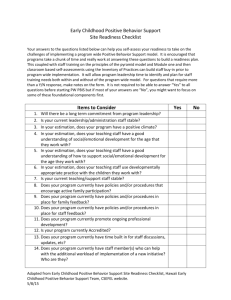

advertisement