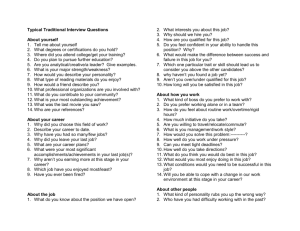

Control Variables

advertisement

The Importance of Being Earnest: Righteous Administrative Leaders Enhances Civil Servants’ Effort Propensity 2 Abstract In recent years, public sector leadership is emerging as a distinctive and autonomous research domain in public administration literature, with one the most studied causal relation being the one between leadership and performance. This study aims at enriching this stream of research by investigating the impact of different public sector leadership behaviors on effort propensity. We rely on an integrated leadership framework and we test hypotheses through a randomized vignette survey which has been carried forward among national government public executives. We compare civil servants’ effort propensity pre and post treatment. Our empirical findings indicate that leaders emphasizing honesty and integrity as core values have a stronger impact on their followers’ motivation compared to other types of leaders. On the contrary, leaders relying on boosting change and innovation seem to have lower impact in motivating followers in working more. Keywords Public sector leadership, federal government, integrity, effort propensity 3 Introduction Public sector leadership is emerging only recently as a distinctive topic of discussion in public administration and public management literature (Van Wart, 2003; Van Slyke and Alexander, 2006). With the nearly unique exception of Selznick’s classic Leadership in Administration (1957) the exploration on which leadership style describes better public executive behavior has been limited (Van Wart, 2003). The main reason for this situation can be easily understood: executives in the public sector had less control and discretion over employees behaviors given strict civil service rules and regulations (Riccucci et al. 2004). In the early Nineties, however, recurrent waves of administrative reforms in most Western countries have increased public sector executives’ autonomy and they have empowered administrative heads in leading governments. The Weberian supremacy of bureaucracy (according to which the less civil servants’ discretion, the better) has been challenged only recently by the so called New Public Management wave which depicted government executives (called ‘public entrepreneurs’) as trapped by red tape and obsolete regulations constraining their leadership skills: elected representatives should have let managers manage, letting them decide on how to reach good performances and administrative goals (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Gore, 1993, Di Iulio, 1994; Guy-Peters, 1996. Kettl, 1997, Light, 1997). Harvard’s political management approach has explicitly claimed that executives having more and more responsibilities for goal settings should even participate to political dialogue about purposes and methods of government (Moore, 1995). Execucrats have therefore emerged as new professional hybrids, above all in national governments (Riccucci, 1995). On one side these professionals exert a different leadership from their political designees: even when elected as directors and executives they perform non policy functions as a significant component of their responsibility (van Wart, 2003). On the other side they differ from business leaders: administrative heads behavior should concern a public service mission including 4 being aware of competing interests, being dedicated to the common good, respecting regulations and enforcing external accountability even in their day-to day behavior (Perry, 1995, van Wart, 2003; Borgonovi, 2007). Recent studies have also highlighted that the main trait of execucrats’ leadership behavior is an integrated one, with a strong presence of ‘transformational’ traits, and a moderate level of ‘transactional’ characteristics (Yukl; 2002, Trottier, Van Wart and Wang, 2008). Integrative leadership studies have also supported the idea that administrative leaders use a combination of practices such as providing clarity of desired outcomes, increasing followers’ intrinsic motivation, recognizing accomplishments, rewarding high performance, as well as by adopting varying degrees of transactional interactions with subordinates (Silvia and McGuire, 2010; Morse, 2010). Few empirical test have been carried forward to assess which leadership role is comparatively more effective in enhancing employees’ productivity or effort. Our research aims at contributing to the administrative leadership literature empirically testing to what extent different public sector leaders style has more impact on subordinates. We rely on Fernandez, Perry and Cho (2010) taxonomy of public sector leadership behavior in carrying forward an experimental vignette study that explore the impact of supervisors’ behaviors on national government civil service performance. 5 Public sector leadership and its effects on employees’ effort propensity: hypotheses From an organizational point of view there is a general agreement that leadership has a positive impact on employees’ performance also in the public sector (van Wart, 2003). Which leadership behavior performs comparatively better in government is however still controversial: the ‘balkanization’ of research on leadership in governments does not increase the clarity of research achievements for managerial practices (Orazi et al. 2013, Yukl, 2012). We rely on Fernandez, Perry, Cho (2010) taxonomy in order to put boundaries on which leadership roles are more frequent in governments. These authors distinguished five leadership roles: taskoriented leadership (defined as a behavior focusing on defining and organizing group activities, setting and communicating goals and performance standards, coordinating followers, monitoring compliance with procedure and goal achievements, providing feedbacks, etc), relation-oriented leadership (which includes a deep concerns by leaders about followers’ welfare and wellbeing, establishing good interpersonal relations among subordinates, treating them as equals, involving them in the decision making process, providing opportunities to personal development), change oriented leadership (which has much in common with transformational leadership as it stresses the importance of fostering change and creativity among employees), diversity-oriented leadership (including those leader’s behaviors directed to increase the quality of decisions by leveraging on followers’ diverse skills, knowledge and background) and integrity-oriented leadership (imposing strong attention by leaders for legality, fairness, and equitable treatment of employees and service recipients) (Fernandez, Perry, Cho, 2010) According to different leadership roles recent literature has found, directly or indirectly, some effects on individual employees’ performances including enhanced productivity and extra effort. 6 Task-oriented leadership and relations-oriented leadership resemble the traditional distinction between concern for production and concern for people in the Blake and Mouton’s managerial grid model (Yukl et al, 2002). The copious amount of studies in leadership suggests that relationshiporiented behaviors are associated more closely with effectiveness (Fisher and Edwards, 1988, Bass, 2008) and this seems to hold also in organizations like governments. Even if the majority of administrative heads in central governments are recognized as ‘transactional’ (Trottier, van Wart, Wang, 2008), Park and Rainey (2008), for example, found a weak relationship between transactional leadership behavior and federal government employees’ job satisfaction or other individual performances. It seems that as the public sector is characterized by a high level of formalization and red tape in particular on hiring, firing, waging and purchasing decisions (Rainey and Bozeman, 2000) it is likely that repeated remarks regarding standard to be respected or process to be followed probably won’t be well accepted in an environment where strict policies and rules are applied. On the contrary, participative- or relations-oriented have overall positive effects on individual job satisfaction (and consequently on individual performance) especially when used in strategic planning process (Kim, 2002) or in establishing good labour-management relations (Kearney and Hays, 1994). Relations oriented leadership and effective communications seem to result in stronger cooperation and organizational commitment by individuals enabling them to perform better in their tasks (Fernandez, 2008). In sum it is likely that task-oriented leadership acts as a negative reinforcement: all leaders must possess it and its absence generates negative outcomes, but its presence alone is not enough to bolster effort. The opposite does not hold for relations-oriented leadership. On theses bases we hypothesize that: H1a: Task-oriented leadership will have a comparatively weaker effects on civil servants’ effort propensity 7 H1b: Relations oriented leadership will have a comparatively higher effects on civil servants’ effort propensity As change and reform have been imperatives for governments in the last decades administrative leaders adopting a change-oriented attitude and behavior have been the preferred unit of analysis of public administration/public management studies (Terry, 1998). This type of leadership includes different types of behaviors such as identifying the best strategic options and alternatives for public organizations they lead, encouraging employees to search for creative solutions to problems, making major change in administrative processes, increasing flexibility and innovation (Fernandez, Cho and Perry, 2010; Yukl, 2002). Such leadership role is often recommended to business leaders, but also the public sector literature has shown consistently that change-oriented leadership often translates into higher perceived performance and job satisfaction (Fernandez, 2008). Charismatic leadership style seems also to enhance the self-esteem of followers (Javidan and Waldman, 2003) More recently, these results have been however criticized. Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri (2011) have in fact found a negative relationship between transformational leadership practices and changeoriented organization citizen behaviors (OCB) (i.e.: employees acting beyond the rules and bringing constructive change in the organizations). They argue that this negative effect of change oriented leader and his follower may be related to the intimidating effect that a charismatic supervisor has on employees in the public sector resulting in less innovative practices at work. Paradoxically “the specific transactional contingent- reward aspect of this relationship is more effective than abstract transformational types of relationship in supporting innovation and creativity, especially among public sector employees (Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri, 2011, p.592)”. Assuming that this effect works also for effort propensity we therefore hypothesize that: 8 H1c: Change-oriented leadership will have a comparatively weaker effects on civil servants’ effort propensity Diversity-oriented leadership, which is principally focused on racial and demographic diversity, attains the advantage given by leveraging on different points of view to obtain an increasing decision making quality, a larger number of ideas and better decision acceptance (Fernandez, Cho and Perry, 2010). Research in this domain has been fragmented but there is a general agreement that good diversity leadership and management foster creativity, greater performance and cohesion (Elron,1997; Cox and Blake, 1991). Diversity management policies, strategies and actions in public administration rely on untested assumptions and no usable empirical knowledge has been available so far (Tschihart and Wise, 2000, Pitts and Wise, 2010). We rely on Pitts (2009) in molding our hypotheses. Using a survey among U.S. federal employees Pitts (2009) indicates that diversity management is strongly linked to both work group performance and job satisfaction. We therefore hypothesize that this holds also when exploring the effects on effort propensity. H1d: Diversity-oriented leadership have a comparatively stronger effects on civil servants’ effort propensity Finally, the integrity-oriented leadership role is particularly relevant in the public sector domain because “the institutionalized and politicized environments in which public managers operate impose strong demands for legality, fairness, and equitable treatment of employees and service recipients” (Fernandez, Cho and Perry, 2010, p. 312). Kakabadse et al. (2003) have further signaled the importance of standards and qualities of governance in addition to the more 9 conventional, limiting norms concerning the technical design of policies, organizations or operating systems. Integrity-oriented leadership can also be advocated as the leadership style on which leadership development programs must focus due to the ethical behaviors and vision it transfer. It seems that focusing on integrity translates to better organizational alignment, cultivation of moral virtues, cheating and finance misuse reduction, job involvement increase, performance increase and countering of alienation and social loafing (Kunthia and Suar, 2004). On these basis we hypothesize that: H1e: Integrity-oriented leadership will have a comparatively stronger effects on civil servants’ effort propensity Methods, Data and Measures As Hunter et al. (2007) have highlighted, an average leadership study (which relies on the distribution of a self-report questionnaire among employees, on using a behaviorally-based leadership assessment tool and on asking for a self-report assessment of employees’ immediate supervisor's behavior) presents some relevant flaws. This type of studies, in fact, typically assume that the subordinate has been exposed to supervisors acting as leaders of any kind, and that supervisors generally possesses some leadership traits (which, as mentioned, is quite rare in public sector organizations). In average leadership studies it is also often assumed that subordinates’ ratings on their supervisors’ behaviors are accurate (which might not hold as conscious biases deriving from social approval might distort the answers) and that the context where leadership occurs simply does not influence leadership roles or its effects on subordinates (Hunter, 2007). Finally, in these leadership studies problematic measurement issues emerge as well: multilevel constructs and hierarchically nested data can create biased statistical results, especially when data 10 are gathered from individuals belonging to the same work teams or the same organization (Van Slyke and Alexander, 2006). In order to avoid these flaws we decided to carry forward a different type of study, a vignette study resembling a field experiment. Vignette methods have been extensively employed in social sciences and consumer behavior research, especially when less accessible attitudes and behavioral patterns have to be assessed (Soydan, 1996). Vignettes are “short descriptions of a person or a social situation which contain precise references to what are thought to be the most important factors in the decision-making or judgment-making processes of respondents” (Alexander and Becker, 1978, p. 94). Consisting of stimuli perceived as real descriptions, vignettes give the respondents the perception that contextual factors are not overcome, but at the same time “the respondent is not as likely to consciously bias his report (…) as he is when being asked directly” (Alexander and Becker, 1978, p. 94). Finally the “systematic variation of characteristics in the vignette allows for a rather precise estimate of the effects of changes (…) in respondent attitude or judgment” (Alexander and Becker, 1978, p. 95). In our study we conceived five vignettes, one for each of the five leadership styles that we wanted to compare: i.e., task-, relations-, change-, diversity-, and integrity-oriented. Each vignette described a scenario in which a hypothetical supervisor embodying one of the five leadership roles communicated to the respondent – i.e. the subordinate – that he/she will join a new project. Each particular leadership role emerged from the portrayed recommendations given by the supervisor about how the subordinate should participate in the project. The vignettes were included in a survey that was administered to a sample of senior civil servants working for the Italian central government. We randomly allocated the five vignettes to participants, with each respondent being presented only one of the five scenarios. The rest of the survey was the same for all respondents. 11 We distributed a questionnaire to five samples of 30 public executives: each questionnaire was different only for the vignette included. We collected data from an assortment of executives in different ministries at different hierarchical levels. In Italy, in fact, national Ministries are organized in Departments or General Directions and Sub-Division. The primary source of data consisted of public executives working in different Ministries and in different Sub-Divisions within the same Ministry. Dependent Variable The dependent variable was the level of effort that participants would put in the project described in the vignette. Following the vignette, were asked: “On a scale from 0% to 100%, in which 0% represents a state of total calm and relax (reading a newspaper in the garden or sleeping on a shore) and 100% represents the maximum employment of your psycho-physical energies (hours and hours of meetings, research and work), how much effort would you put in the project?” Before featuring the vignette, the questionnaire asked participants to report the level of effort that they ordinarily expended at work: “On a scale from 0% to 100%, in which 0% represents a state of total calm and relax (reading a newspaper in the garden or sleeping on a shore) and 100% represents the maximum employment of your psycho-physical energies (hours and hours of meetings, research and work), how much effort would do you usually put in your work?” This double request of effort propensity allowed us to minimize the limit of self-report measurements, conducting our analysis on performance on the basis of the variation between the average daily level of effort and the leadership-stimulated level of effort. 12 Vignette methods require a contextual measure that can quickly catch the respondent’s response to the stimuli. As real performance can be only measured in a field experiment or in laboratory conditions, effort propensity could have been easily assessed by respondents. In order to study the link between leadership styles and effort propensity we have asked for the general effort proneness of every respondents through the After the vignette description, the respondents were asked to provide their effort propensity. Manipulated Variables The five leadership styles were the manipulated the manipulated variables. They have been included in the survey in the vignette section in the form of different leadership behaviors. We first drafted a neutral scenario for which the five leadership dimensions were set to zero: this scenario resulted in a basic supervisor’s proposal to work for a new project. In their study, Fernandez, Cho and Perry (2010) proposed 16 statements (each linked to a particular leadership roles) to measure integrative leadership (see Appendix A). We introduced into the neutral scenario groups of statements related to a given leadership style to form a specific leadership style vignette. The respondents were then asked to report the effort they would put in the described project. Every scenario was also followed by a “scenario realism” question. In a preliminary test on 24 civil servants, we noticed that the level of perceived realism of the scenario scored very different values, from 1 to 10, with an average of 4.49. Qualitative interviews revealed that the respondents’ majority that selected low value of realism were intended to communicate not that the scenario wasn’t accurate o incomplete, but that some of the behaviors presented were rare or totally absent in their public context. We slightly changed the vignette in order to make it more realistic. 13 Control Variables Public service motivation was included as a control variable in the analysis, alongside with contextual and socio-demographic variables. Public service motivation (PSM) has been defined by Perry (1996) as “an individual's predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions”. Through confirmatory factor analysis Perry was able to end up to a model composed by four elements: attraction to public policy making, which can be exciting and dramatic and can reinforce one's image of self-importance; commitment to the public interest, essentially altruistic even when the public interest is conceived as an individual's opinion (Downs, 1967); compassion, an extensive love of all people within political boundaries and the imperative that they must be protected in all of the basic rights granted to them; and self-sacrifice, the willingness to substitute service to others for tangible personal rewards. Given this characteristics, PSM is likely to influence the relationship we wanted to investigate. We measured PSM with a widely-used, 5-item version of Perry’s (1996) original scale (Alonso and Lewis 2001; Brewer, Selden, and Facer 2000; Kim 2005; Pandey, Wright, and Moynihan 2008; Wright and Pandey 2008, Christensen and Wright 2011). Results Data were gathered by e-mail submission (607 surveys submitted, 155 completed). After the elimination of incomplete surveys, the ending data set used for this study consisted of 153 respondents. The five vignette-related surveys have been randomly assigned to the sample (see Table 1). No significant differences have been found within the groups, confirming the overall homogeneity and the validity of the random assignment. 14 Tab. 1: Leadership style scenario distribution Among 153 questionnaires 58 were completed by civil servants pertaining to the Ministry of Economics and Finance (37,9%), 41 by managers pertaining to the Ministry of Economic Development (26,8%), 23 by directors accountable to the Ministry of Justice (15%), 10 by civil servants accountable to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities (6,5%) and 21 by various managers associated with the Ministries of Defense, foreign Affairs, Agriculture, Forest and Alimentary Politics, and the Ministry of University and Instruction (13,8%). Referring to demographic variables, 45,1 % of the sample is composed by females (69) and 54,9% by males (84), with an average age of 51 years. For what concerned contextual variables, we investigated tenure as a scale variable and wage and number of subordinates as ordinal variables. The mean for tenure is 21,4 years of public service (St. deviation=10.08). Approximately half of the sample (49,7%, 76 respondents) is responsible for a number of subordinates ranging from 0 to 10, 21,6% of the sample (33) is responsible for a number of subordinates ranging from 11 to 25, 13,1% of the sample (20) is responsible for a number of subordinates ranging from 26 to 50, another 13,1% of the sample (20) is responsible for a number of subordinates ranging from 51 to 100, and only 2,6% (4) declared to manage between 100 and 200 subordinates. 15 A paired t-test on the difference between effort level post and before treatment was conducted to assess the impact of each leadership style on effort and, consequently, expected performance (see Table 2). Paired t-tests showed a significant decrease in effort propensity for participants exposed to change-oriented leadership (∆ effort= -5.0 scale points, one-tail p-value=.027) and a significant increase in effort propensity among participants exposed to integrity-oriented leadership (∆effort= +8.0 scale points, two-tailed p-value=.000). No significant pre-post treatment changes showed up for the other three treatments – i.e., task-oriented leadership (∆ effort= +0.3031 scale points, two-tail p-value= 0.931), relations-oriented leadership (∆ effort= +1.5384 scale points, one-tailed p-value= 0.291), and diversity-oriented leadership (∆ effort= +3.0 scale points, two-tail p-value= 0.213). Tab. 2: Differences in Effort pre-treatment/Effort post-treatment for each leadership style 16 An ANOVA test showed that integrity-oriented leadership style is overall significant at the 0.01 level in influencing effort propensity (F [9, 143]= 3.31, p-value=.005) (see Table 3) Tab. 3: ANOVA on Effort Difference (pre and post) by Leadership Style (Bonferroni) Task-Oriented Relations-Oriented Change-Oriented Diversity-Oriented Integrity-Oriented 1.2354 1.000 -5.30303 1.000 2.6969 1.000 7.69697 0.379 RelationsOriented ChangeOriented DiversityOriented -6.53846 0.869 1.46154 1.000 6.46154 0.9999 8 0.299 13 0.005 5 1.000 Control variables were included to assess potential moderating effects of public service motivation in the relationship between leadership style and the effect on effort propensity, pre and post treatment. A linear regression between leadership styles and public service motivation showed that PSM has no significant relation with effort propensity for the first four leadership style (F [9, 143]= 3.31, R-squared= 0.1484). However, a significant relation has been found between PSM and integrity-oriented leadership: this leadership style is more effective when applied to civil servants’ with lower public service motivation (P>|t|= 0.05, Beta= -1.565). This result opens the path for interesting hypothesis discussed in the next paragraph. Discussion and Conclusions The recent birth of many national leadership development programs highlights governments’ strong will to improve public leaders and managers’ skills and performances, but which leadership style can be the core of an effectively designed leadership training program for 17 civil servants? Our analysis tries to answer to this interrogative. We presented five hypotheses, assessing a particular relationship between a specific leadership style and the desired outcome – in this case, subordinates’ effort propensity. Three out of the five hypotheses were confirmed by the analysis, suggesting that civil servants may be “accustomed” to certain leadership styles and react less positively to them than what is commonly hypothesized in literature. As a matter of fact taskoriented leadership (H1a accepted), relations-oriented leadership (H1b refused) and diversityoriented leadership (H1d refused) do not influence significantly performance. In the new public management era, it’s likely to suppose that supervisors’ transactional behaviors such as communicating clear goals and providing feedbacks are commonly expected by public administration subordinates from their leaders, along with relation-oriented behaviors (i.e. work recognition and empowerment) and diversity-oriented behaviors (i.e. acceptance of different points of view regardless of age, sex and race in order to increase the quality of decisions). These three leadership styles constitute the core traits and competencies that administrative leaders must possess nowadays. Change-oriented leadership (H1c accepted), however, does not fit well any longer in the public administration arena. As shown by Fernandez (2005), the high level of red tape related to hiring and buying policies, the high number of hierarchical levels and the massive presence of bureaucracy and policies tend to form a barrier to innovative leadership. Integrityoriented leadership (H1e accepted) proves to be the only leadership style able to increase subordinates’ performance in the public sector. Standards and qualities of governance are vital in addition to conventional norms concerning the technical design of policies, organizations or operating systems. Evidently one important limit of our study relies on the context in which it took place. It might be possible that leader’s integrity influence followers’ behavior above all in countries like Italy where the level of corruption in the public sector is relatively high. Future 18 studies replicating our research protocol in countries experiencing lower level of dishonesty in government can assess the magnitude of the context. 19 Selected references Alexander CS and Becker HJ (1978) The Use of Vignettes in Survey Research. Public Opinion Quarterly 42 (1): 93-104. Alonso P and Lewis GB (2001). Public Service Motivation and Job Performance. Evidence from the Federal Sector. The American Review of Public Administration 31 (4): 363-380. Andersen JA (2010) Public versus private managers: how public and private managers differ in leadership behavior. Public Administration Review 70 (1): 131-141. Andrews R and Boyne GA (2010) Capacity, leadership and organizational performance: testing the black box model of public management. Public Administration Review 70 (3): 443-454. Bass BM (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press, New York. Blake RR and Mouton J(1964). The managerial grid: Key orientations for achieving production through people. Houston, TX: Gulf. Brewer GA, Coleman Selden S, and Facer RL (2000). Individual Conceptions of Public Service Motivation. Public Administration Review 60 (3): 254-264 Burns JM (1978). Leadership. Harper and Row, New York. 20 Christensen RK and Wright BE (2011). The Effects of Public Service Motivation on Job Choice Decisions: Disentangling the Contributions of Person-Organization Fit and Person-Job Fit. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (4): 723-743 Crozier M (1976) The dynamics of bureaucracy: A case analysis in education. Wiley, New York. Currie G and Lockett A (2007) A critique of transformational leadership: moral, professional and contingent dimensions of leadership within public services organizations. Human Relations 60 (2): 341-370. Deci EL, Connell JP and Ryan RM (1989) Self-Determination in a Work Organization. Journal of Applied Psychology 74 (4): 580-590. Downs A (1967) Inside Bureaucracy. Real Estate Research Corporation, Chicago. Dull M (2009) Results-model reform leadership: questions of credible commitment. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (2): 255-284. Fairholm MR (2004) Different perspectives on the practice of leadership. Public Administration Review 64 (5): 577-590. Fernandez S (2005) Developing and testing an integrative framework of public sector leadership: evidence from the public education arena. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (2): 197-217. 21 Fernandez S, Cho YJ and Perry JL (2010) Exploring the link between integrated leadership and public sector performance. The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 308-323. Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill. Grant AM (2008), Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (1): 4858. Hammer M and Champy J (1993). Reengineering the Corporation A: Manifesto for Business Revolution. New York: Harper Collins. Hanbury GL, Sapat A and Washington CW (2004) Know yourself and take charge of your own destiny: the "fit model" of leadership. Public Administration Review 64 (5): 566-576. Horwitz SK and Horwitz IB (2007) The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: A metaanalytic review of team demography. Journal of Management 33 (6): 987-1015. House RJ (1977). Leadership: the cutting edge. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale. Hunter ST, Bedell-Avers KE and Mumford MD (2007) The typical leadership study: assumptions, implications and potential remedies. The Leadership Quarterly 18 (5): 435-446. 22 Jas P and Skelcher C (2005) Performance decline and turnaround in public organizations: a theoretical and empirical analysis. British Journal of Marketing 16 (3): 195-210. Javidan M and Waldman DA (2003) Exploring charismatic leadership in the public sector: measurement and consequences. Public Administration Review 63 (2): 229–242. Kakabadse A, Korac-Kakabadse N and Kouzmin A (2003) Ethics, values and behaviours: comparison of three case studies examining the paucity of leadership in government. Public Administration 81 (3): 477–508. Kim SE and Lee JW (2009) The impact of management capacity on government innovation in Korea: an empirical study. International Public Management Journal 12 (3): 345–369. Kochan T et al. (2003) The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resource Management 42 (1): 3–21. Kotter JP (1999). John P. Kotter on what leaders really do: A Harvard business review book. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School. Kunthia R and Suar D (2004) A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. The Leadership Quarterly 49 (1): 13-26. Morreale SA (2009) Preparing leaders in public administration. Northeast Business & Economics Association Proceedings 132-139. 23 Morse RS (2010) Integrative public leadership: catalyzing collaboration to create public value. The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2) 231-245. Nanus B (1992) Visionary Leadership: Creating a Compelling Sense of Direction for Your Organization. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Inc. Northouse, P. G. (1997) Leadership: Theory and practice. Thous and Oaks, CA: Sage. Orazi DC and Turrini A (2012) Public Sector Leadership 2012: Styles, development and efficacy in the New Public Management Era, forthcoming. Pandey SK, Wright BE and Moynihan DP (2008). Public Service Motivation and Interpersonal Citizenship Behavior in Public Organizations: Testing a Preliminary Model. International Public Management Journal 11 (1): 89-108 Park SM and Rainey HG (2008) Leadership and public service motivation in US federal agencies. International Public Management Journal 11 (1): 1-33. Parry KW and Proctor-Thomson SB (2003) Leadership, culture and performance: the case of New Zealand public sector. Journal of Change Management 3 (4): 376-399. Perry JL (1996) Measuring Public Service Motivation: An Assessment of Construct Reliability and Validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 6 (1): 5-22. 24 Peters T and Austin N (1985). A Passion for Excellence. The Leadership Difference. New York: Random House. Rainey HG (2003) Understanding and managing public organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. Roseman IJ (1991) Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions. Cognition and Emotion 5 (2): 161– 200. Silvia C and McGuire M (2010) Leading public sector networks: an empirical examination of integrative leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 264-277. Soydan H (1996) Using the Vignette Method in Cross-Cultural Comparisons. Cross-national research methods in the social sciences (10). Biddies Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn. Trottier T, Van Wart M and Wang XH (2008) Examining the nature and significance of leadership in government organization. Public Administration Review 68 (2): 319-333. Van Slyke DM and Alexander RW (2006) Public service leadership: opportunities for clarity and coherence. The American Review of Public Administration 36 (4): 362-374. Van Wart M (2003) Public-sector leadership theory: an assessment. Public Administration Review 63 (2): 214-228. 25 Webber, S. S., & Donahue, L. M. (2001) Impact of highly and less job-related diversity on work group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management 27 (1): 141-162. Wright BE and Pandey SK (2008). Public Service Motivation and the Assumption of Person— Organization Fit. Testing the Mediating Effect of Value Congruence. Administration & Society 40 (5): 502-521 Yukl G (2002) Leadership in Organizations. Prentice Hall. 26 Appendix Appendix 1: 2006 Federal Human Capital Survey items Items used to construct integrated leadership measure, source: 2006 Federal Human Capital Survey, U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Task-oriented leadership role I1. Managers communicate the goals and priorities of the organization. I2. I know how my work relates to the agency's goals and priorities. I3. Managers promote communication among different work units (for example, about projects, goals, and needed resources). I4. Managers review and evaluate the organization's progress toward meeting its goals and objectives. I5. Supervisors/team leaders provide employees with constructive suggestions to improve their job performance. Relations-oriented leadership role I6. I am given a real opportunity to improve my skills in my organization. I7. Supervisors/team leaders in my work unit provide employees with the opportunities to demonstrate their leadership skills. I8. Employees have a feeling of personal empowerment with respect to work processes. I9. Supervisors/team leaders in my work unit support employee development. Change-oriented leadership role I10. I feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things. I11. Creativity and innovation are rewarded. Diversity-oriented leadership role I12. Supervisors/team leaders in my work unit are committed to a workforce representative of all segments of society. I13. Managers/supervisors/team leaders work well with employees of different backgrounds. Integrity-oriented leadership role I14. My organization's leaders maintain high standards of honesty and integrity. I15. Prohibited Personnel Practices (for example, illegally discriminating for or against any employee/applicant, obstructing a person's right to compete for employment, knowingly violating veterans' preference requirements) are not tolerated. I16. I can disclose a suspected violation of any law, rule or regulation without fear of reprisal. 27 Appendix 2: Leadership-style Vignettes (translation from Italian) Vignettes employed in the experimental section of the survey. The green highlighted part refers to the leadership specific items imported from the HCS described in Appendix 1. Task-oriented leadership role Imagine the following situation. You are convened by your boss to discuss about a very important project. The project is a priority for the public administration you work and your participation to the project is considered fundamental. During the meeting your boss clearly identifies goals and objectives to be achieved (I3) and the resources at your disposal (I1, I2, I4). He/she gives you many useful advice to lead the project team and to achieve the targeted results (I5). Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. In the end your boss inform you about the members of the team: a middle aged colleague you perfectly know and a young intern. Before exiting the office your boss’ adds “Don’t worry if you need more resources: I will do everything to support you for any of your needs” Relations-oriented leadership role Imagine the following situation. You are convened by your boss to discuss about a very important project. The project is a priority for the public administration you work and your participation to the project is considered fundamental. During the meeting your boss clearly highlights that this project is not only important for the organization but also for your personal development and career (I8): working for this project will improve your skills as a professional (I6) and as a manager (I7). Your boss tells you also that he/she will be supportive and close to you for any advice at any time (I9). Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. In the end your boss inform you about the members of the team: a middle aged colleague you perfectly know and a young intern. Before exiting the office your boss’ adds “Don’t worry if you need more resources: I will do everything to support you for any of your needs” Change-oriented leadership role Imagine the following situation. You are convened by your boss to discuss about a very important project. The project is a priority for the public administration you work and your participation to the project is considered fundamental. During the meeting your boss clearly highlights that you will have total freedom in choosing how to develop the project (I10) and you will be compensated for any improvement or change in the way people work (I11). Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. In the end your boss inform you about the members of the team: a middle aged colleague you perfectly know and a young intern. Before exiting the office your boss’ adds “Don’t worry if you need more resources: I will do everything to support you for any of your needs” 28 Diversity-oriented leadership role Imagine the following situation. You are convened by your boss to discuss about a very important project. The project is a priority for the public administration you work and your participation to the project is considered fundamental. Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. In the end your boss informs you about the members of the team: an Afro American young colleague and a colleague of yours that is openly gay (I12). Your boss highlights that working with them should be an opportunity to enrich competencies and the results of the project (I13) Before exiting the office your boss’ adds “Don’t worry if you need more resources: I will do everything to support you for any of your needs” Integrity-oriented leadership role Imagine the following situation. You are convened by your boss to discuss about a very important project. The project is a priority for the public administration you work and your participation to the project is considered fundamental. Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. Your boss highlights how important the project is for your organization and that you must respect general administrative rules and guidelines, without taking personal initiatives. In the end your boss inform you about the members of the team: a middle aged colleague you perfectly know and a young intern. Before exiting the office your boss’ adds “I am telling you: don’t be tempted to incur in extra costs (I14). Working in governments means being honest and righteous (I15): if you came to know about colleagues violating rules or norms, you should communicate it and you will get a compensation (I16)” 29