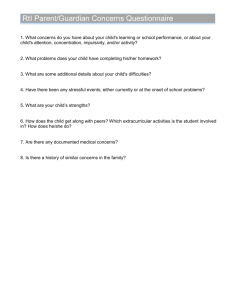

Thomas, J.H., Bowling, J. R., Fox, R., & Dula, C. S. (2010, November).

advertisement

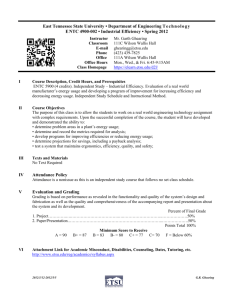

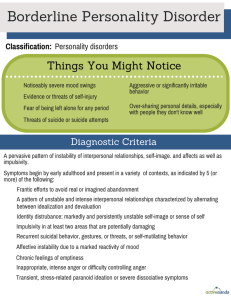

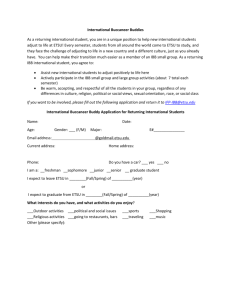

DWI (Driving While Impulsive): Investigating Relationships Between Impulsivity and Dangerous Driving in a Simulated Environment Jesse Thomas, Justin Bowling, Russell Fox, & Chris S. Dula APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY LABORATORY East Tennessee State University http://www.etsu.edu/apl/ Johnson City, Tennessee INTRODUCTION METHOD Although innovations and improvements to automobile safety have decreased some driving risks, motor vehicle crashes remain a serious public health problem and are one of the leading causes of death in the United States (Hilton & Shankar, 2003; NHTSA, 2003). Participants: Participants were 26 undergraduate students from a small university in the Southeastern United States. Impulsivity is a personality trait that has been defined as ‘‘a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions to oneself or others” (Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz, & Swann, 2001). The inability to control impulses can undermine the intentions of an individual, leading to poor decision making (Nordgren, van der Pligt, & Harreveld, 2007; Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998). Previous research has reported that time perception is influenced by impulsivity, which could contribute to impulsive individuals exhibiting an faster cognitive processing speed with increased activity levels (Barratt, 2002) Dangerous driving behaviors include intentional acts of aggression, negative emotions, and risk taking behaviors (Dula & Geller, 2003). Dangerous behaviors may occur without the presence of negative emotion or intent to harm (Willemsen, Dula, Declercq, & Verhaeghe, 2008). The literature suggests that impulsiveness may increase the probability of dangerous driving behaviors (Dahlen, Martin, Ragan, & Kuhlman, 2005; Deffenbacher, Filetti, Richards, Lynch, & Oetting, 2003). This study investigated the relationship between levels of impulsivity, reaction time, and dangerous driving behaviors. There were at total of 15 females (57.7%) and 11 males (42.3%), with a range from 19 years of age to 39 years of age (Mean = 23.88, SD=5.63). Participants scheduled a time to come into the lab to participate in a the driving simulator study, via an online participant managing system. Measures: Vigil Continuous Performance Task (VCPT). Participants’ level of impulsivity, as well as average reaction time in responding to stimuli, was assessed by their total number of errors of commission and their average delay time on the VCPT, respectively. STISIM Drive™ Computer Simulated Driving Program. Dependent variables collected by the computer program included: total number of speeding events, percent of driving time spent speeding, the total amount of time taken to complete the course, total number of collisions, and the total number of center line crossings. Procedure: After obtaining informed consent, participants completed the Vigil Continuous Performance Task (VCPT). Participants were then led to a computer driving simulator apparatus, and instructed to drive the course as safely as possible and obey all traffic laws while maneuvering through the course. Participants drove a course that was 6.44 miles in length. The course included driving obstacles such as traffic light decisions, passing on a twolane road, and pedestrian crossings. Participant’s driving behavior was then assessed by calculating the total number of dangerous driving behaviors listed above. HYPOTHESES RESULTS H1: It was hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between number of errors of commission on the Vigil Continuous Performance Task and propensity to speed in a simulated driving environment (i.e. number of speed exceedences, percent of time speeding, and amount of time taken to complete the course). H1: There was a significant relationship between errors of commission on the VCPT and the number of speed exceedences at a p<.05 level (r=.407). There was a significant relationship between errors of commission on the VCPT and amount of time taken to complete the course at the P<.01 level (r=-.526). There was no significant relationship between errors of commission on the VCPT and percentage of time spent speeding (r=.318). H2: It was also hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between number of errors of commission (impulsiveness) and average delay time (reaction time) on the Vigil Continuous Performance Task. H3: Additionally it was hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between number of errors of commission on the Vigil Continuous Performance Task and the other dangerous driving variables listed in the Method section of this poster. RESULTS (CONT.) H2 : It was also hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between number of errors of commission (impulsiveness) and average delay time (reaction time) on the VCPT. There was a significant relationship between these two measures on the P<.01 level (r = -.413) H3 : There was a significant relationship between the number of errors of commission on the VCPT and the numbers of collisions at the P<.05 significance level (r=-.444). There was no significance between the errors of commission on the VCPT and the number of centerline crossings (r = .285) DISCUSSION Results showed a significant positive relationship between errors of commission on the VCPT and the number of speed exceedences. This means that as errors of commission increased, so did the number of speed exceedences. This suggests that individuals with higher of levels of impulsivity may be inclined to speed a great number of times while driving. Additionally a significant negative relationship between the number of errors of commission on the VCPT and the amount of time taken to complete the simulated driving course was observed. In other words, as errors of commission increased, course completion time decreased. This would make sense if those with higher impulsivity did indeed exceed the posted speed limit more often. There was no significant relationship between the errors of commission on the VCPT and the total percent of time spent speeding. Since there was a positive relationship with the number of speed occurrences, this could mean that individuals with higher levels of impulsivity repeatedly corrected their speeds to the posted limit only to raise it again. There was a significant positive relationship between numbers of errors of commission and average delay time on the VCPT. This means that as the number of errors of commission increased, the average delay time also increased. This could suggest that the individuals in this study with higher levels of impulsivity took longer to react to stimuli in the VCPT. There was a significant positive relationship between the number of errors of commission on the VCPT and the number of collisions in the simulated driving course. This means that as the number of VCPT commission errors went up, so did collisions. There was no significant difference between the number of VCPT commission errors and center line crossings. Limitation: Could have used a more diverse sample to see if findings generalize to populations other than those consisting of college students. Future Research: Future research should measure the time it takes drivers to react to obstacles in a simulated driving environment. REFERENCES References available upon request CONTACT: Jesse H. Thomas thomasjh@goldmail.etsu.edu, Justin Bowling bowlingjr@goldmail.etsu.edu, Russell Fox foxr@goldmail.etsu..edu, or Chris S. Dula dulac@etsu.edu