Summary of Act III Outside the Capitol, Caesar appears with Antony

advertisement

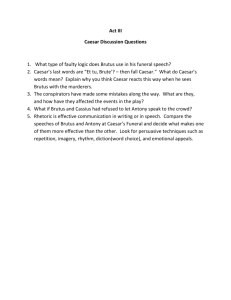

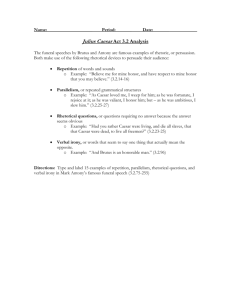

Summary of Act III Outside the Capitol, Caesar appears with Antony, Lepidus, and all of the conspirators. He sees the Soothsayer and reminds the man that “The Ides of March are come.” The Soothsayer answers. “Aye, Caesar, but not gone.” Artemidorus calls to Caesar, urging him to read the paper containing his warning, but Caesar refuses to read it. Caesar then enters the Capitol, and Popilus Lena whispers to Cassius, “I wish your enterprise to-day may thrive.” The rest enter the Capitol, and Trebonius deliberately and discretely takes Mark Antony offstage so that he will not interfere with the assassination. At this point, Metellus Cimber pleads with Caesar that his brother’s banishment be repealed; Caesar refuses and Brutus, Casca, and the others join in the plea. Their pleadings rise in intensity and suddenly, from behind, Casca stabs Caesar; as the others also stab Caesar, he falls and dies, saying “Et tu Brute!” While the conspirators attempt to quiet the onlookers, Trebonius enters with the news that Mark Antony has fled home. Then the conspirators all stoop, bathe their hands in Caesar’s blood, and brandish their weapons aloft, preparing to walk “waving our red weapons o’er our heads” out into the marketplace, crying “Peace, freedom, and liberty!” A servant now enters bearing Mark Antony’s request that he be permitted to come to them and “be resolved/How Caesar hath deserved to lie in death.” Brutus grants the plea and Antony enters. Antony gives a farewell address to the dead body of Caesar; then he pretends a reconciliation with the conspirators, shakes the hand of each of them, and requests permission to make a speech at Caesar’s funeral. This Brutus grants him, in spite of Cassius’s objections. When the conspirators have departed, Antony begs pardon of Caesar’s dead body for his having been “meek and gentle with these butchers.” He predicts that “Caesar’s spirit, ranging for revenge,” will bring civil war and chaos to all of Italy. A servant enters then and says that Octavius Caesar is seven leagues from Rome, but that he is coming. Antony tells the young man that he is going into the marketplace to “try,/In my oration, how the people take/The cruel issue of these bloody men.” He wants the servant to witness his oration to the people so that he can relate to Octavius how they were affected. The two men exit, carrying the body of Caesar. Brutus and Cassius enter the Forum, which is thronged with citizens demanding satisfaction. They divide the crowd—Cassius leading off a portion to hear his argument, and Brutus presenting reasons to those remaining behind at the Forum. After he mounts the rostrum, Brutus asks the citizens to contain their emotions until he has finished, to bear in mind that he is honorable, and to use their reason in order to judge him. Brutus says that he loved Caesar more than any man present, and that when he killed Caesar, he did not love him less; he “loved Rome more.” He asks them what they would prefer to be—slaves, governed by a living Caesar or free men, freed by Caesar’s death? He grieves for Caesar, his dead friend, and he celebrates Caesar’s successes, and he honors his valor, but he says that he was compelled to kill him because of Caesar’s tyrannical ambition. He feels that his actions could only offend the ignorant or the unpatriotic, and he asks if anyone is offended. The citizens all respond that they are not offended, and Brutus refers them to documents placed in the Capitol that explain why Caesar’s death was necessary. He then brings the crowd’s attention to Antony, entering with Caesar’s body, and he assures them that Antony was not a part of the conspiracy. He concludes his oration by promising to slay himself when his own death will benefit his country. The crowd emotionally cries out that he should be given honors and made dictator and king. Brutus calms them and instructs them to hear Antony; then he exits to acclamations that they will obey him, that Caesar was a tyrant, and they they will listen attentively to Antony. Antony begins his oration with the now-famous “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;/I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.” He indicates that, like Brutus, he will deliver a reasoned oration. He refers to Brutus’s accusation that Caesar was ambitious, and he acknowledges that he speaks with “honourable” Brutus’s permission, but he questions if Caesar’s well-known generosity in sharing the spoils of victory with the public and his compassion for the poor are consistent with condemnations of ambition. He also points to Caesar’s refusal of the crown three times at the Feast of Lupercal: is this the act of a man dangerously ambitious: the crowd considers Antony’s words, the wrong done Caesar, Caesar’s now questionable “ambition,” and Antony’s sorrow and nobility. Antony resumes speaking and laments that none of the citizens seems to feel humble enough to honor the mighty Caesar. He professes that he would prefer to wrong Caesar, himself, and even his audience rather than wrong “such honourable men” as Brutus and Cassius by stirring the citizens to riot. He then displays a piece of parchment which he says is Caesar’s will, and he claims that the common people would profoundly mourn and search for mementoes of their benefactor, Caesar, if they were to hear the contents of the will, but that he does not intend to read the will (he knows, of course, that the crowd will demand that he read it, which they instantly do). Then Antony continues, telling them that Caesar’s generosity to them would anger them too much; he may have wronged “the honourable men/ Whose daggers have stabb’d Caesar.” The citizens then denounce the conspirators as murderers, and thy demand that Antony read Caesar’s will. Antony pretends submission and steps down among them to stand beside the body of Caesar. He lifts Caesar’s cloak, points to the wounds in it that were slashed by the knives of the conspirators, and he refers to Brutus as Caesar’s very dear friend and “angel”, whose stab “was the most unkindest cut of all.” Commending the citizens for being moved to tears by the sight of the torn and bloody cloak, he removes it to expose the body itself. The crowd’s reaction is, first, one of pity; then they become angry and disperse, uttering cries for revenge. Under the pretense of not wanting to stir them to riot and mutiny, Antony calls them back and suggests that the “honourable” men (the assassins) will no doubt provide acceptable reasons for the assassination and, speaking with supreme irony, he confesses to lacking Brutus’s oratorical power, being himself only a “plain blunt man.” But, he continues, if he had Brutus’s ability to persuade, he would move the very “stones of Rome to rise and mutiny.” Now that the suggestion has been uttered, the mob rushes off wildly to search for the conspirators. One more time Antony calls them back to remind them that they have forgotten Caesar’s will. He says that Caesar left seventy-five drachmas to every male Roman citizen, and the crowd praises Caesar’s nobility. Caesar also left them his woodlands, walks, and orchards on the Forum side of the Tiber, and Antony inquires when they can expect another ruler like Caesar. Shouting “Never,” they leave to cremate Caesar’s body with due reverence, to burn the houses of the assassins, and to wreak general destruction. Antony is content; he muses, “Mischief, thou art afoot,/ Take thou what course thou wilt!” A servant enters then and informs Antony that Octavius has arrived and is with Lepidus at Caesar’s house. Antony is pleased and decides to visit him immediately to plan to take advantage of the chaos he has created. The servant reports that Brutus and Cassius have fled Rome, and Antony suspects that they have heard of his rousing the people to madness. Cinna the poet is on his way to attend Caesar’s funeral when he is accosted by a group of riotous citizens who demand to know who he is and where he is going. He tells them that his name is Cinna and his destination is Caesar’s funeral. They mistake him, however, for the conspirator Cinna and move to assault him. He pleads that he is Cinna the poet and not Cinna the conspirator, but they reply that tey will kill him anyway because of “his bad verses.” With Cinna captive, the crowd exits, declaring their intent to burn the houses belonging to Brutus, Cassius, Decius, Casca, and Ligarius.