2007 UMT

advertisement

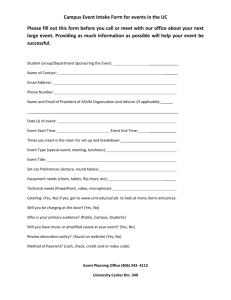

PRINCIPLES OF FINANCE University of Management and Technology 1901 N. Fort Myer Drive Arlington, VA 22209 USA Phone: (703) 516-0035 Fax: (703) 516-0985 Website: www.umtweb.edu © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-1 FIN100 Chapter 2: The Financial Markets and Interest Rates Keown, Petty, Martin, and Scott Foundations of Finance: The Logic and Practice or Financial Management (with EVA Tutor Package) (4th ed.) © 2003 Prentice Hall © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-2 FIN100 Learning Objectives To understand: Internal and external sources of funds Mix of corporate securities sold Why financial markets exist U.S. financial market system Investment banking Private Placements © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Flotation costs SEC Regulation Rates of return and interest rate determination Term structure of interest rates Multinational firms, efficient markets and inter-country risk Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-3 FIN100 Federal Reserve Actions The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the U.S. It is active in trying to control inflation and the rate of growth of the economy. From Feb 4, 1994 to Dec 11, 2001, the Federal Reserve System (The Fed) voted to change the target funds rate on 31 occasions Rates were moved upward 14 times Rates were moved downward 17 times Rates moved downward 11 consecutive times in 2001 © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-4 FIN100 Federal Funds Rate The Federal Funds rate establishes the short-term market rate of interest It serves as a sensitivity indicator of the direction of future changes in interest rates The Fed manipulates rates as one of its tools for: Maintaining the maximum sustainable rate of employment Maintaining prices (with a general bias toward some inflation preferred to no inflation) © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-5 FIN100 Internal and External Funds Firms oten find themselves with an opportunity that internally generated funds will not be sufficient to finance. In these circumstances, managers look to external sources of cash (capital) to pay the bills. Businesses rely heavily on external funding, which in turn means there is an active market system that enables the exchanges. This market system must be organized and resilient. Economic contractions will continue to occur. Businesses will invest in risky projects that may fail or more produce fewer profits than projected © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-6 FIN100 Market Conditions and External Funds Changes in market conditions influence the way corporate funds are raised. Example: High interest costs discourage the use of debt. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-7 FIN100 The Mix of Corporate Securities in The Capital Market The sale of corporate stock is NOT the financing method most relied upon. Debt is the dominant financing method. Equities 26.40% Bonds and notes payable. Also, the U.S. tax system favors debt as means of raising capital Interest Expense is tax deductible Dividend payaments are not deductible © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu Bonds and Notes 73.60% 2-8 FIN100 Financial Markets Financial markets are institutions and procedures that facilitate transactions in all types of financial claims. The facilitate the transfer of savings from economic units with a surplus to economic units with a deficit. That is, they transfer financial assets (e.g., cash) from lenders to borrowers. The borrowers use the borrowed financial assets to pay for real assets (e.g., to buy new equipment) or to cover the costs of providing products or services to the market. Remember, customers want to buy goods and services on credit and then tend to pay late; and sometimes they do not pay at all. Therefore, businesses must have excess cash to pay debts before the customers pay for the goods or services received. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2-9 FIN100 Real and Financial Assets Real Assets are tangible assets such as houses, equipment and inventories. Financial Assets are claims for future payment on other economic units, e.g., common and preferred stock. Underwriting is the purchase of financial claims of borrowing units and resale at a higher price to investors. Secondary Markets trade in already existing financial claims. Financial Intermediaries are the major financial institutions i.e. commercial banks, savings and loans, credit unions, life insurance companies, mutual funds etc. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 10 FIN100 Movement of Funds Through the Economy Financial institutions facilitate the flow Direct Transfer of Funds The firm that needs money sells its securities directly to investors. Indirect Transfer of Funds using an Investment Banker The firm sells its securities as a block to a syndicate of investors for a price; the syndicate then sells the stocks to the public at a higher price. Indirect Transfer of Funds Using the Financial Intermediary A financial intermediary (e.g., an insurance company or a pension fund) collects the savings of individuals, issuing its own (indirect) securities in exchange for the savings. The financial intermediary then invests the funds to acquire other assets, such as stocks and bonds, with the aim of achieving higher returns than are promised to those who gave their savings. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 11 FIN100 Structure of U.S. Financial Markets When a corporation needs to raise external capital, funds can be obtained by a: Public Offering - where individuals and institutional investors have the opportunity to purchase securities or Private Placement - where securities are sold to a limited number of investors © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 12 FIN100 Primary and Secondary Markets Primary Markets Securities are offered for the first time to investors – a new issue of stock. The effect is to increase the total stock (supply) of financial assets outstanding in the economy. Secondary Markets Transactions take place using currently outstanding securities. All transactions after the initial purchase are in secondary markets. Transactions do not affect the total stock of financial assets that exist in the economy. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 13 FIN100 Money Market and Capital Market Money Market Short-term debt instruments with maturities of one year or less E.g., Treasury Bills, Federal Agency Securities, Bankers Acceptances, Negotiable Certificates of Deposit, Commercial Paper. Capital Market Long-term financial instruments with maturities that extend beyond one year. E.g., Term Loans, Financial Leases, Corporate Equities and Bonds © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 14 FIN100 Organized Security Exchanges and Over-the –Counter Markets Organized Security Exchanges These are tangible entities where financial instruments are traded on their premises. National and regional exchanges New York Stock Exchange American Stock Exchange Chicago Stock Exchange Over-the-Counter Markets Includes all security markets except the organized exchanges © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 15 FIN100 Benefits of Organized Exchanges Both corporations and investors enjoy benefits from the operation of organized security exchanges. Provides a continuous market: Trades take place on a continuing basis, with knowledge of prices from prior transactions affecting current transaction, thus reducing price volatility (to an extent). Establishes and publicizes fair security prices: Competitive forces (buying and selling) reach a price point that balances sellers and buyers. Helps businesses raise new capital: With an organized market, it is easier to “float” a new stock offering. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 16 FIN100 Listing Requirements Exchanges set a number of criteria that a given security must meet before it can be listed. Listing criteria varies from exchange to exchange. NYSE is the most stringent in the world. General requirements of NYSE include: Profitability: Earning before tax of at least $2.5 million in the most recent year and at least $2.0 million for the prior 2 years Market Value: Revenues for the most recent fiscal year must be at least $100 million and the global market capitalization must be at least $1 billion. Public Ownership: There must be at least 1.1 million publicly held common shares, distributed among at least 2,000 holders of at least 100 shares or more each. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 17 FIN100 Investment Banker An investment banker is a financial specialist involved as an intermediary in the merchandising of securities. He/she acts as a “middle person” to facilitate the flow of savings from economic units that want to invest to those units that want to raise funds. An investment banker may a firm or a person. In the wake of the Great Depression, the Banking Act of 1933 (known as the Glass-Steagall Act) required commercial banks to cease all investment activities. In 1999 the Financial Modernization Act (Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act) repealed Glass-Steagall and allows the combination of financial activities, including commercial and investment banking along with insurance and securities brokerage. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 18 FIN100 Functions of an Investment Banker Underwriting Term is borrowed from insurance industry; it means “assuming the risk.” The investment banker forms a syndicate of other investment bankers who are invited to help buy and resell the stock issue. On a specific day, the corporation raising funds by the sale of stock is given a check in exchange for the shares. The investment bank then owns the shares and can proceed to sell them to whoever is willing to buy them. The corporation has its cash and can use it as it wishes. It is not affected by the stock price offered to the public. The investment bankers (the syndicate) can sell all or a portion of the stock to the public in hopes of earning profits. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 19 FIN100 Functions of an Investment Banker (cont’d) Distributing Once the syndicate owns the shares, it must get them into the hands of willing investors. This is the distribution or selling function of investment bankers. The investment bankers may have branch offices across the nation that seek to sell shares. Or it may have arrangements with securities dealers who regularly contact their clients to buy and sell new offerings. Advising Investment bankers are experts in issuing and marketing securities, so the expectation is that they maintain a high level of awareness of market conditions and the value of securities. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 20 FIN100 Distribution Methods Corporations may place a new security offering in the hands of final investors in several ways: Negotiated Purchase: investment banker agrees to a price the syndicate will pay (e.g., $2 less than the closing price on the first day of issue). This approach is prevalent. Competitive Bid: several underwriters bid for the right to issue the security. Most auctions are confined to three situations: (1) railroad issues, (2) public utility issues, (3) state and municipal bond issues. Commission or Best Efforts Basis: investment banker acts as an agent rather than as a principal. The securities are not underwritten. Instead, each banker tries to sell the issue in return for a fixed commission. A successful sale is not guaranteed. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 21 FIN100 Distribution Methods (cont’d) Privileged Subscription: When a firm believes it has a distinct market for its new securities, it may offer the new issue only to a definite and select group of investors. Three common target markets are: (1) current stockholders, (2) employees, and (3) customers. Offering directly to current stockholders are called rights offerings. The company may arrange a standby agreement with an investment banker, who will underwrite the offering if the privileged subscription is does not raise all that is needed. Direct Sales: The firm sells stock directly to investing public itself. This approach is relatively rare today. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 22 FIN100 Private Placements Private placement is an alternative to a public offering or to a privileged subscription. The goal still is raise funds, but the most likely security instrument is a bond or note payable. Private placement is not limited to fixed-income securities. There is an extensive, organized venture capital market. Private placement is attractive to small- and medium-sized businesses. The major investors in private placements are large financial institutions such as insurance companies and pension funds. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 23 FIN100 Private Placements (cont’d) Advantages Speed: There is no SEC filing and no bureaucracy to manage. Reduced Flotation Costs: The lengthy registration process with the SEC is avoided and underwriting costs do not have to be absorbed. Financing Flexibility: The firm deals on a face-to-face basis and may tailor the arrangements in detail. E.g., a “line of credit” may be arranged so that the entire debt need not be accepted at once. Or there is the chance to renegotiate later. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 24 FIN100 Private Placements (cont’d) Disadvantages Interest Costs: Interest costs are greater than on public issues. Restrictive Covenants: Divident policy, working-capital levels, and the raising of additional debt capital may be affected by the terms of the agreement. Possible Future SEC Registration: In some cases, the lender may want to sell the issue to the public before maturity, in which case, the lender may require the borrower to agree in advance to the possible future SEC registration – which may be costly. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 25 FIN100 Flotation Costs There are two types of flotation costs, which are the costs that accrue to the firm that is trying to raise capital: Underwriter’s Spread: the difference between the gross proceeds from the issue and the net receipts by the company. Issuing Costs: include (1) printing and engraving, (2) legal fees, (3) accounting charges, (4) trustee fees, and (5) miscellany. According to the SEC, flotation cost Are significantly higher for common stock than preferred stock Are significantly higher for preferred stock than for bonds. Thus, the costs reflect the difference in risk. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 26 FIN100 Market Regulation Primary Markets Securities Act of 1933: Aims to provide potential investors with accurate, truthful disclosure about the firm and new securities being offered. Secondary Markets Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Created SEC to enforce federal securities laws Securities Acts Amendments of 1975: Created a national market system © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 27 FIN100 Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Major security exchanges must register with the SEC Insider trading is regulated Prohibits manipulative trading SEC control over proxy procedures Gives Board of Governors of Federal Reserve System responsibility for setting margin requirements © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 28 FIN100 Shelf Registration Formally called a SEC Rule 415 registration, a shelf registration is a master registration statement that covers the financial plans of the firm over the coming two years. With the approval of the SEC, the firm can sell some or all of the securities over the two-year period covered by the shelfregistration. Before each piecemeal sale of securities, a brief registration statement is filed with the SEC giving notice. A shelf registration allows a firm to use the market as a virtual “line of credit” based on the sale of securities in the open market © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 29 FIN100 Rates of Return in Financial Markets Users of funds (borrowers) compete with one another to obtain the capital needed from savers (lenders). Offering higher rates of return is an obvious tactic. Opportunity Cost of Funds The rate of return on the next best investment alternative to the investor. Critical to financial management. History teaches us the rates of return vary over time. Inflation may be used as an “average” of sorts. If your investments do not keep up with inflation, then you are losing money daily. The variability or returns compared to average inflation can be used to compute a standard deviation that can be useful. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 30 FIN100 Rates of Return in Financial Markets (cont’d) Data from 1926 to 2000 indicate that the average annual rate of inflation has been 3.2 percent. The investor who earns only 3.2 percent has zero “real return” on investment. The inflation-risk premium, therefore, is 3.2 percent. Default-risk premium is an additional charge to cover the potential the borrower will not repay. The U.S. government is assumed to be a zero-risk borrower. For the period 1926-2000, the government paid 5.7 percent. In contrast, corporations paid 6 percent. So we surmise there is a 0.3 percent (30 basis points) default-risk premium on corporate debt. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 31 FIN100 Rates of Return in Financial Markets (cont’d) We also would expect a higher default-risk premium for common stock. The data from 1926 to 2000 support this thinking. The average annual rate of return on stocks was 13 percent. Subtracting the 6 percent return on corporate bonds, we arrive at a risk premium of 7 percent for common stock. Nominal interest rates are those shown by fixed income securities. Subtracting the rate of inflation, we obtain an estimate of the “real” interest rate. Investors will not accept a rate of return that is less than the rate of inflation…at least, smart investors will not anyway. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 32 FIN100 Rates of Return in Financial Markets (cont’d) Investors also demand additional premiums: Maturity Premium: Additional return required by investors in long-term securities to compensate them for the increased risk of price fluctuations on those securities caused by interest rate changes Liquidity Premium: Additional return required by investors in securities that cannot be quickly converted into cash at a reasonably predictable price. For example, shares of a bank holding company traded on the NYSE (e.g., SunTrust) will be more liquid – that is, more easily converted to cash when needed – than common stock in the Citizens Bank of Fairfax. Therefore, the Citizens Bank of Fairfax must offer greater total returns (which may include dividends) than SunTrust. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 33 FIN100 Interest Rates in a Nutshell The nominal interest rate, or the quoted rate, is the interest paid on debt securities without an adjustment for any loss in purchasing power. It is the rate you would find in the Wall Street Journal for a specific fixed-income security. k = k* + IRP + DRP + MP + LP Where, k = nominal interest rate (i.e., the rate that is quoted) k* = the real risk-free rate of interest (cf, Treasury bond rate) IRP = inflation-risk premium DRP = default-risk premium MP = maturity premium LP = liquidity premium © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 34 FIN100 Nominal Risk-Free Rate Sometimes we wish to focus on the nominal risk-free rate of interest. This is the risk-free rate plus the inflation-risk premium. krf = k* + IRP This rate is much debated and is a source of constant discussion among financial economists. We can be pragmatic and use the U.S. Treasuries lowest interest rate (likely the 3-month) as a proxy for k* and then add 3.2 percent as a reasonable guess for IRP. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 35 FIN100 Estimating Specific Interest Rates Using Published Data A reasonable estimate for a nominal interest rate for a new issue can be calculated using historical data. Instead of looking at 50 years, you probably would look at the most recent few years and several projections for future rates. k* = the difference between the average return of the 3-month T-bill and inflation over the same period. IRP = the average inflation over the period. DRP = the difference between the 30-yr Treasury bond and Aaa-rated corporate bonds MRP = the difference between the average yield on 30-yr Treasury bonds and 3-month Treasury bills. LRP = whatever you think is best, depending on the market you will have. Then compute k = k* + IRP + DRP + MRP + LRP. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 36 FIN100 Effects of Inflation Nominal Rate of Interest When a rate of interest is quoted, it is the nominal rate unless otherwise indicated. Real Rate of Interest The real rate of interest represents the rate of increase in actual purchasing power, after adjusting for inflation. Fisher Effect The nominal rate of interest (using the risk-free rate) is the sum of the real rate of inflation (k*) plus the inflation risk premium (IRP) plus the real rate times the IRP (as an additional adjustment): krf = k* + IRP + (k* • IRP) © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 37 FIN100 Inflation and Real Rates Financial analysts often use an approximation method to estimate the real rate of interest over a selected past time frame. Using published data on inflation rates, the following formula may be applied k* = Nominal Interest – Inflation Rate © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 38 FIN100 Term Structure of Interest Rates © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Term Structure of Interest 14 12 10 Interest Rate The relationship between a debt security’s rate of return and the length of time until the debt matures is known as the term structure of interest rates or yield to maturity. The term structure reflects observed rates or yields on similar securities, except for the time to maturity. As a general rule, the longer the time to maturity, the higher the interest rate. 8 6 4 2 0 1 5 10 15 20 25 Years to Maturity Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 39 FIN100 Term Structure of Interest Rates A number of theories have been offered to explain the term structure of interest rates: Unbiased Expectations Theory The term structure is determined by expectations about future interest rates. Liquidity Preference Theory Investors require maturity premiums to compensate them for buying securities that have a longer time to maturity and hence expose them to greater risks of interest rate fluctuations Market Segmentation Theory The rate of interest for a particular maturity is determined solely by demand and supply for securities with that maturity and is independent of the demand and supply of maturities with different maturities. © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 40 FIN100 Efficient Financial Markets and Intercountry Risk One of the reasons underdeveloped countries are indeed underdeveloped is that they lack a financial market system that has earned the confidence of those who must use it. The development of industry and the creation of real capital assets requires financial market mechanisms to operate. Operating in a foreign country creates various risks: Financial System Risk: The financial systems may not be stable and may lack integrity. Political System Risk: Governments change and may align with anti-Western factions, placing foreign assets at risk of conversion or destruction Exchange Rate Risk: Currency fluctuations in world markets can quickly devalue a currency, destroying its value © 2007 UMT Version 07167 Visit UMT online at www.umtweb.edu 2 - 41 FIN100