Self-management support - California Health Care Safety Net Institute

Self-management support

Thomas Bodenheimer MD with lots of help from

Improving Chronic Illness Care

Self-management support is more than patient education

• Patient education

– Information and skills are taught

– Usually disease-specific

– Assumes that knowledge creates behavior change

– Goal is compliance

– Health care professionals are the teachers

• Self-management support

– Skills to solve patientidentified problems are taught

– Skills are generalizable to all chronic conditions

– Assumes that confidence yields better outcomes

– Goal is increased selfefficacy

– Teachers can be professionals or peers

Why is self-management support important?

• Every person self-manages his/her chronic condition. 99% of chronic care decisions are made by the patient away from the health care system

• The question is, does the person selfmanage well or poorly?

• Managing well improves clinical outcomes

Self-management support and compliance/adherence

• Compliance/adherence may not be helpful concepts

• Noncompliance or non-adherence assumes that 1) the patient has the information needed to make healthy decisions, and 2) the patient was involved in the decisions

• Often, neither 1) nor 2) is true

Compliance/adherence

• Compliance: “the extent to which a person’s behavior

(in terms of taking medications, following diets, or executing lifestyle changes) coincides with medical or health advice.” Lutfey and Wishner, Diab Care

1999;22:635.

• Adherence “the extent to which a patient’s behavior (in terms of taking medication, following a diet, modifying habits, or attending clinics) coincides with medical or health advice.” McDonald et al. JAMA 2002;288:2868.

Compliance/adherence

• Compliance and adherence are synonyms

• They are also the same as “patient selfmanagement behaviors” or “healthy behaviors”

• Use the term “healthy behaviors” as having the same meaning as compliance or adherence

• “Healthy behaviors” doesn’t compare patients with some professionally-set standard

Compliance/adherence

• For doctors, the word “compliance” (with practice guidelines) is appropriate

• Docs chose to be docs. They should held to a standard: do what’s evidence-based

• Patients didn’t choose to be chronically ill. They can’t be held to a standard

• For patients, the words “compliance/ adherence” are less appropriate

Many people fail to choose healthy behaviors because they lack information

• One study: 76% of patients with type 2 diabetes received limited or no diabetes education

• 300 medical encounters: doctors spent average 1.3 minutes giving information

• Another study: only 37% of patients were adequately informed about medications they were taking

Clement, Diab Care 1995;18:1204. Waitzkin. JAMA 1984;252:2441

Many people choose unhealthy behaviors because they lack information

• 50% of patients leave office visit not understanding what the doctor said

• Study of 264 visits to family physicians. During patient initial statement of the problem, physician interrupted after average of 23 seconds.

• Failure to provide information to patients about their chronic condition is associated with unhealthy behaviors. If people don’t know what to do, they don’t do it

O’Brien et al. Medical Care Review 1992;49:435. Kravitz et al.

Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1869. Roter and Hall. Ann Rev

Public Health 1989;10:163. Marvel JAMA 1999;281:283.

Information is necessary but not sufficient

• Information by itself does not improve clinical outcomes; people with diabetes gaining knowledge about their condition do not have lower HbA1c than those uninformed.

Norris et al. Diab

Care 2001;24:561

• An additional factor is needed

• That additional factor appears to be collaborative decision making, which makes the patient an active participant in his/her management.

Patients in empowerment classes have lower

HbA1c than controls.

Anderson, Funnell. Diabetes Care

1995;18:943.

Many people choose unhealthy behaviors because they were not involved in clinical decisions

• Study of 1000 physician visits, the patient did not participate in decisions 91% of the time

• When patients are involved in decisions, healthrelated behavior is improved and clinical outcomes (for example HbA1c levels) are better than if patients are not involved

Braddock et al. JAMA 1999;282;2313. Heisler et al. J Gen Intern

Med 2002;17:243. Greenfield et al. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3:448

Back to compliance/adherence

• One cannot expect a patient to “comply” with a physician’s advice if the patient doesn’t understand the advice

• One cannot expect a patient to “adhere” to a physician’s advice if the patient doesn’t agree with the advice

• Much “noncomplance/nonadherence” (i.e. unhealthy behaviors) is related to inadequate information-giving and lack of collaborative decision making

Does self-management support attempt to improve patient compliance/adherence?

• No, the purpose of self-management support is to encourage patients to become informed and activated

– By providing information

– By encouraging collaborative decision-making

– By assisting people to set their own goals

• Many (not all) patients will choose goals that do improve their health-related behaviors

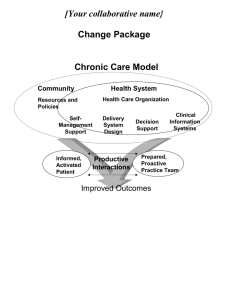

Chronic Care Model

Community Health System

Resources and Policies Health Care Organization

Self-

Management

Support

Delivery

System

Design

Decision

Support

Clinical

Information

Systems

Informed,

Activated

Patient

Productive

Interactions

Prepared,

Proactive

Practice Team

Functional and Clinical Outcomes

Informed, activated patient

Key conclusion:

Informed, activated patients have healthier behaviors and improved clinical outcomes

Golin et al. Diab Care 1996;19:1153. Piette et al. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:624.

Francis et al. N Engl J Med 1969;280:535. Roter. Health Educ Monographs

1997;5:281. Greenfield, Kaplan et al. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3:448. Heisler et al. J

Gen Intern Med 2002;17:243.

Informed, activated patient

Requires:

Information-giving

Collaborative decision-making

These are the two parts of selfmanagement support

The 15-minute system

Short, unplanned MD visit, no team

Patient not taught about her illness

No collaborative decision making

Uninformed, passive patient

Unprepared practice team

We need to redesign primary care delivery systems to provide selfmanagement support, which creates informed, activated patients

Information-giving

Collaborative decision-making

The 5 A’s

• A clinical algorithm used for tobacco cessation

• Has become part of the US Public Health

Service guidelines on quitting smoking www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/5steps.htm

• It has been adopted for other healthrelated behaviors

ASSESS

Knowledge

Beliefs,

Behavior,

Barriers,

Confidence

Self-management support in office practice

ADVISE

Provide personalized information about condition and benefits of change

ASSIST

Use motivational techniques and teach problem-solving

AGREE

Collaborative goal and action plan

ARRANGE

Follow-up and resources

Assess

• Knowledge

• Skills

• Importance

• Confidence

• Supports

• Barriers

• Risk Factors

Let’s look at Importance and Confidence

Bubble chart

Kate Lorig’s question: “Is there anything you would like to do this week to improve your health?”

Other things?

Physical activity

Reducing stress?

Taking medications

Healthy diet

Checking sugars

If patient picks a domain, assess readiness to make a change

• Readiness = importance and confidence

• If patient doesn’t think it’s important, he/she won’t make a change. Give information

• If patient thinks change is important, but has no confidence that he/she can change, assess and try to increase confidence

Assessing Importance

“How important do you think it is to exercise to improve your blood sugar?”

Not at all convinced

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Totally convinced

Patient says 4

“Why 4 and not zero?”

“What would it take to move it to a 8?”

(From Keller and White, 1997; Rollnick, Mason and Butler, 1999)

Assessing Confidence

How confident are you that you can exercise to improve your blood sugar?

Not at all confident

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Totally confident

Patient says 4

“Why 4 and not zero?

“What would it take to move it to an 8?”

Advise

Provide specific personalized information about the chronic illness, the health risks and the benefits of change

Advise: provide information

• Information-giving is disease-specific

• Telling people 150 facts about diabetes does not work. It is far more effective to find out what people want to know, and give them the information they want.

• Also, make sure people understand the information given them

• 2 tools

– Ask-tell-ask

– Closing the loop

Advise: Ask-Tell-Ask

• When patients are given a lot of information, they regain only a small amount

• Ask-tell-ask: Ask patients: “What do you know about your diabetes, and what would you like to know? When patients say what they want to know, tell them. Then ask again: what do you think about what you heard, and are there other things you want to know?

Advise

• A study of patients with diabetes found that in only12% of patient visits, the clinician checked to see if the patient understood what the clinician had told the patient

• This is called “closing the loop”

• In 47% of cases of closing the loop, the patient had not understood what the physician said

• When closing the loop took place, HbA1c levels were lower than when it did not take place

• Closing the loop should be an integral part of advising patients

Schillinger et al. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:83

.

Agree

Collaboratively select goals and an action plan to meet those goals

Action plan

1. Something you WANT to do

2. Describe

How

What

Where

Frequency

When

3. Barriers

4. Plans to overcome barriers

5. Confidence rating (1-10)

6. Follow-Up plan

Source: Lorig et al, 2001

Action plan: example

1. Something you WANT to do: Get more activity

2. Describe:

How: With friend

What: Walk

When: After lunch

Where: 3 times around block

Frequency: Mon, Wed, Fri, Sat

3. Barriers: Forget

4. Plan to overcome barriers: Put a note on fridge

5. Confidence rating (1-10): 7

6. Follow-Up plan: medical assistant will call me next week

Action plan

• Base goals on patient priorities

• Action plans are specific steps to help achieve goals

• Action plans should be easily achievable with confidence level 7 or greater

• Purpose is to increase self-efficacy: a person’s confidence that he/she can make changes to improve life

Assist

Problem-solving to help overcome barriers to achieving goals

Problem Solving

1. Identify the problem.

2. List all possible solutions.

3. Pick one.

4. Try it for 2 weeks.

5. If it doesn’t work, try another.

6. If that doesn’t work, find a resource for ideas.

7. If that doesn’t work, accept that the problem may not be solvable now.

Source: Lorig et al, 2001

Arrange

Schedule follow-up to provide ongoing assistance and support to adjust or change or problem-solve the action plan as needed

Arrange: follow-up

• Try a wide variety of methods, whichever patient prefers (in-person, phone, email)

• Make sure follow-up happens, patient trust can be destroyed by missed follow-up

• Use outreach and community opportunities

• Easiest is to see if patient wants to go a group, in which case follow-up takes place in the group

• Follow-up can be done by other patients (buddy system)

Opportunities for self management support

• Before the Encounter

• During the Encounter

• After the Encounter

From Russ Glasgow, PhD

Opportunities for self management support

Before the Encounter

• Pre-visit contact (phone, mail, e-mail, PDA, touchscreen computer, student, medical assistant)

• Pamphlets on “Talking to

Your Provider”

Pre-activation of patients

• 10 minute meeting with health educator to help patients formulate questions for physician led to more patient involvement in decisions

[Roter. Health Educ Monographs

1997;5:281]

• Interactive pre-visit booklet -- to write down agenda topics and learn techniques for recalling physician advice -- led to better retention of information and healthier behaviors -- lifestyle changes and medication use

[Cegala et al. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:57]

Pre-activation of patients

• 20-minute pre-visit meeting to prepare patients with diabetes to participate in decision-making

• Pre-activated patients had greater control over visit agenda (shown by audiotapes) than control patients

• Pre-activated patients had better HbA1c levels than control patients

Greenfield, Kaplan et al. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3:448

Opportunities for self management support

During the Encounter

• Assess what goals patient wants to work on

• See if patient willing to discuss action plan

• Information-giving (ask-tellask)

• Closing the loop

• Referral to community resource

Planned chronic care visits

• Group diabetes visits at Kaiser/Permanente led by nurse educator: significantly lower HbA1c levels and lower hospital use compared with controls

[Sadur et al.Diab

Care 1999;22:2011]

• Diabetes “mini-clinics” at Group Health in Seattle: for patients who regularly attended the clinics, better glycemic control than usual care patients

[Wagner et al.

Diab Care 2001;25:695]

Planned chronic care visits

• Nurse-led diabetes planned visit clinic had better HbA1c levels than controls

[Peters, Davidson.

Diab Care 1998;21:1037]

• Planned diabetes visits with nurse and endocrinologist had lower mortality and lower incidence of MI, revascularization, angina,

ESRD than control patients; median follow-up was 7 years

[So et al. Am J Managed Care 2003;9:606]

• Patients attending planned diabetes empowerment classes had lower HbA1c levels compared with controls

[Anderson, Funnell et al. Diab

Care 1995;18:943]

Planned chronic care visits

• Planned visits are essential to assist people to adopt healthy behaviors

• Planned visit is antidote to “tyranny of the urgent” -- acute issues crowding out chronic care management

• Visits can be with nurses, pharmacists, health educators, nutritionists, promotoras, or trained patients

• Group or individual visits

Opportunities for self management support

After the Encounter

• Referrals (health educator, medical assistant, community resource)

• Phone, e-mail, web follow-up

• Peer support (buddy system)

• Chronic disease selfmanagement course

Regular, sustained follow-up

• VA system: nurse-initiated phone contacts between visits improved glycemic control compared with usual care

[Weinberger et al. J Gen

Intern Med 1995;10:59]

• Cochrane Review: 5 RCTs -- better HbA1c levels in patients with regular follow-up compared with controls

[Griffin, Kinmouth. Cochrane

Library, Issue 3, 2001]

• Regular follow-up is a predictor of proper medication use

[Dunbar-Jacob. Health Psychology

1993;12:91]

Regular, sustained follow-up

• Diabetes education without regular follow-up is unlikely to result in longterm behavior change success

[Clement. Diab

Care 1995;18:1204]

• Follow-up can be done by visits with any caregiver, in groups, patient buddies, promotoras, telephone, e-mail, web

Chronic Disease Self-

Management Program

• Developed and studied by Kate Lorig and colleagues at Stanford

• Peer-leaders (patients with chronic illness), 6 sessions, 2 1/2 hours each

• Addresses multiple conditions

• Goal-setting, action plans, problem solving, skill acquisition

• Patients call each other between sessions

• Outcomes: improved health behaviors and health status, fewer hospitalizations; some improvements sustained for 2 yrs

Lorig et al. Medical Care 1999;37:5, 2002;39:1217

Who can do goal-setting, action plans, follow-up?

• Trained peers

• Health educators

• Nurses

• Physicians

• Medical assistants

• Students

• Any caring person...

Resources

• Book: Rollnick et al. Health Behavior Change. 1999.

• Book: Lorig, Holman, Sobel et al. Living a Healthy

Life with Chronic Conditions. 2nd edition. Palo Alto,

Bull Publishing, 2001.

• Bibliography on self-management: www.improvingchroniccare.org

• Download Action Plan forms in English, Spanish and

Chinese: www.action-plans.org

Web resources

• www.bayerinstitute.com

provides provider training in “Choices and Changes”

• www.motivationalinterview.org

has books, videos and training

• www.stanford.edu/group/perc home of Chronic

Disease Self-Management Program

Take-home points

• Self-management support includes

– Information-giving

– Collaborative decision-making

– Goal-setting/problem-solving

• It can be done before, during, and after a primary care visit. Planned chronic care visits are the ideal place

• A primary care physician cannot do selfmanagement support alone. It takes a team.