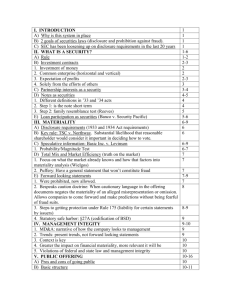

Liability under Securities Act of 1933

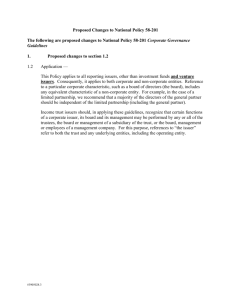

advertisement