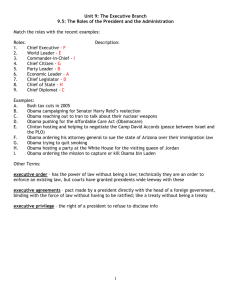

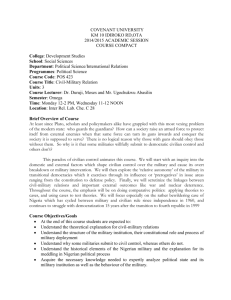

Civil Military Relations Disadvantage/Joint Chiefs of Staff CP

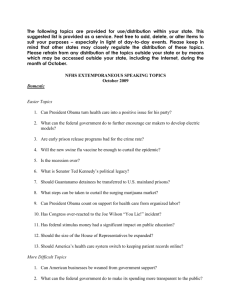

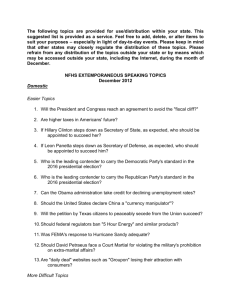

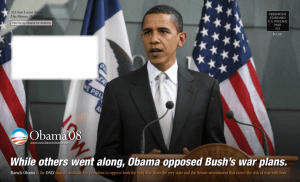

advertisement