File - The Fish in Prison

advertisement

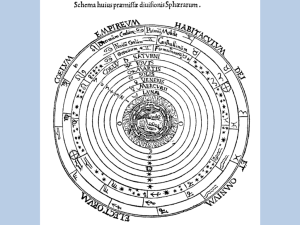

When I had seen all this sight, In this noble temple thus [thus meaning "in this fashion," or "as I have just described to you"] "Ah, Lord," I thought, "[you] who created us," [literally, "who made us"] I have never before seen such nobility Of artworks, nor such richness, [meaning the fancy/expensive trappings] As I saw engraved in this church, But I do not know who made them, Nor where I am, nor in what country. [i.e. in what place, generally] But now I will go out and see Right at the door, if I can See anywhere any stirring man [stirring as in "waking," most likely] Who might [be able to] tell me where I am. When I came out from the doors, I quickly looked around me. Then I saw [nothing] but a large field, For as far I was able to see, Without any town, or house, or tree. Key "Scientific" Concepts from Books I and II of HoF: 1) dream theory / dream guides 2) "kyndely enclynyng": gravitation and more 3) sound theory and the fluid mechanics of fame 4) spaceflight and the inhabitants of inner and outer space 5) astronomical learning? No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two, Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool, Deferential, glad to be of use, Politic, cautious, and meticulous; Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse; At times, indeed, almost ridiculous— Almost, at times, the Fool. --from T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock If you're wondering how he eats and breathes And other science facts, Just repeat to yourself "It's just a show, I should really just relax... For Mystery Science Theater 3000." The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings. [...] He also alleged a fact which travelers have confirmed: In the vast Library there are no two identical books. From these two incontrovertible premises he deduced that the Library is total and that its shelves register all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographical symbols (a number which, though extremely vast, is not infinite): Everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels' autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books. When it was proclaimed that the Library contained all books, the first impression was one of extravagant happiness. All men felt themselves to be the masters of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal or world problem whose eloquent solution did not exist in some hexagon. The universe was justified, the universe suddenly usurped the unlimited dimensions of hope. As was natural, this inordinate hope was followed by an excessive depression. The certitude that some shelf in some hexagon held precious books and that these precious books were inaccessible, seemed almost intolerable. A blasphemous sect suggested that the searches should cease and that all men should juggle letters and symbols until they constructed, by an improbable gift of chance, these canonical books. The authorities were obliged to issue severe orders. The sect disappeared, but in my childhood I have seen old men who, for long periods of time, would hide in the latrines with some metal disks in a forbidden dice cup and feebly mimic the divine disorder. [...] On some shelf of some hexagon (men reasoned) there ought to exist a book that may be the perfect cipher and compendium to all the rest... [...] I cannot combine certain characters dhcmrlchtdj which the divine Library might not have foreseen and which do not, in any of its secret languages, entail a terrible meaning. No one can pronounce a syllable that is not filled with tendernesses and fears, that is not the powerful name of a god in one of those languages. [...] I venture to suggest this solution to the ancient problem: The Library is unlimited and cyclical. If an eternal traveler were to cross it in any direction, after centuries he would see that the same volumes were repeated in the same disorder (which, thus repeated, would be an order: the Order). My solitude is gladdened by this elegant hope. "To see a world in a grain of sand And a heaven in a wild flower, Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, And eternity in an hour." --William Blake, "Auguries of Innocence" And whan that he [Troilus] was slayn in this manere [that is, by Achilles], His lighte goost ful blisfully is went Up to the holughnesse of the eighthe spere, In convers (converse/opposite side) letyng ("letting" i.e. abandoning) everich element; And ther he saugh with ful avysement (deliberation, consideration) The erratik sterres, herkenyng armonye With sownes ful of hevenyssh melodie. And down from thennes faste he gan avyse (see, consider) This litel spot of erthe that with the se Embraced is, and fully gan despise This wrecched world, and held al vanite To respect of the pleyn felicite That is in hevene above; and at the laste, Ther he was slayn his lokyng down he caste, And in hymself he lough right at the wo Of hem that wepten for his deth so faste, And dampned al oure werk that foloweth so The blynde lust, the which that may nat laste, And sholden al oure herte on heven caste; And forth he wente, shortly for to telle, Ther as Mercurye sorted hym to dwelle. --Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde Book V.1807-1827)