Word - Wake Forest College

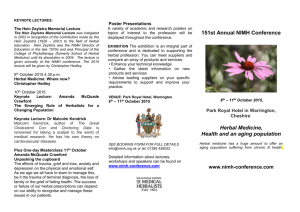

advertisement