PPTX - Bonham Chemistry

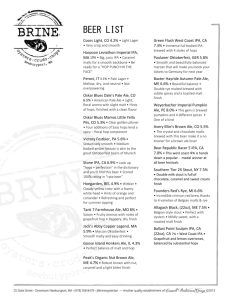

advertisement

Brewing Science Flavor and the Origins of Flavor Beer Styles What is a flavor? • A combination of taste, odor, and other sensory input – Includes mouth feel (tactile), visual, kinetsthetic, temperature, pain (nocioception), and other senses (carbonation!) • The largest contributors are taste and smell Taste • The taste buds are clusters of approximately 100 taste cells that occur as protuberances, called papillae, on the tongue • The arrival of a chemical stimulant on the surface of a receptor temporarily modifies the cell wall and produces an electrochemical impulse Smell • perceived by neurons in the olfactory epithelium (skin cells) of the upper respiratory passage • Some molecules also reach this olfactory ephithelium by way of the back of the mouth during swallowing; this is known as gustatory aroma perception Other Senses • Tactile sensations such as viscosity and the prickle from dissolved carbon dioxide, for example, are determined by the physical composition of the beer and also play an important role in zymological evaluations. • Temperature is extremely important for all aspects of flavor perception. Warmer temperatures tend to emphasize the aromatic components of the beer, while lower temperatures suppress them. It is therefore imperative to serve beer at the proper temperature for the style. • Psychological factors or the senses of vision and hearing, which may indirectly affect the results of a beer evaluation. A trained taster should be able to minimize the influence of these external factors while performing a sensory analysis. How do we measure Flavor? • Meilgaard system: concentration relative to sensing threshold value • Beer Flavor Wheel • “False” measures: IBU and Color • Strength / Alcohol Content • Others Meilgaard Thresholds Primary Flavor Constituents (>2 FU) All Beers Ethanol Hop bittering compounds Carbon dioxide Specialty Beers Hop aroma compounds Caramel and roasted flavor compounds Esters and alcohols (high gravity beers) Short-chain acids Defective Beers 2-trans-nonenal (oxidation) Vicinal diketones (diacetyl) Sulfur compounds (H2S, DMS) Acetic acid (contamination) 3-Methyl-2-butene-1-thiol (lightstruck) Others (contamination) Secondary Flavor Constituents (0.5-2 FU) Volatiles Banana esters (e.g., isoamyl acetate) Apple esters (e.g., ethyl hexanoate) Fusel alcohols (e.g., isoamyl alcohol) C6, C8, C10 aliphatic acids Ethyl acetate Butyric and isovaleric acids Phenylacetic acid Nonvolatiles Polyphenols Various acids, sugars, and hop compounds Tertiary flavor constituents (0.1-0.5 FU) 2-Penethyl acetate, o-amino acetophenone Isovaleraldehyde, methional, acetoin 4-Ethylguaiacol, g-valerolactone Background flavor constituents (< 0.1 FU) Remaining flavor compounds International Bittering Units • Distinct from Flavor profile • Based on UV/Vis measurement of extracted iso-alpha acids Color • Degrees Lovibond is derived from comparison of color to standardized scale, largely replaced by other methods (Standard Reference Method) that give approximately equal results • SRM measures light at 430 nm: SRM = 12.7 x dilution factor x Abs430 Malt Analysis Color • Traditional Method developed by Lovibond. The scale is implemented by comparing colored slides or glasses to a sample to visually see which slide agreed with the color of the sample • Current standards for measuring color – Standard Reference Method (SRM) developed by American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC) – European Brewing Convention (EBC) color rating – The two methods can be compared by the equation EBC = 1.97 * SRM Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Color • The current methods use spectrophotometers • All three scales goes from low to high, with lower numbers assigned to light colors • For light colored beers the SRM method is very close to the Lovibond scale Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Alpha-amylase (Dextrinizing Units) • ASBC metric that measures dextrin units per 100 grams • Over modified malt normally has lower dextrin units. For less modified malts, the dextrinizing units needs to be greater to apply an infusion mash. • Typical ranges for 100 grams: – – – – Six row malt 35-45 American two row malt 40-50 Pilsener malt 44-48 Vienna malt 40-45 Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Diastatic Power (Degrees Linter) • Measures the enzyme content of the malt. Specifically, the enzyme strength to convert starch to sugar • Higher diastatic power malts convert starches faster than lower diastatic power malts • Well modified malts with low protein content typically have a diastatic power between 35 and 40. On the other hand, it can be as high as 160 for six row brewers malt. • Diastatic power decreases as malt color increases. Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Protein Percent • Equals 6.25 times the total nitrogen content • The protein percent for Barley malt should be 9 to 11% • Enzymes are proteins, so higher protein levels correspond to higher enzymatic strength. Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Soluble Nitrogen/Total Nitrogen Ratio • The ratio of soluble nitrogen to total nitrogen is a measure of malt modification. A higher ratio indicates higher malt modification • For lager malts, 30-33% indicates under modification and 37-40% indicates over modification. • For infusion mashing, the ratio should be 3842% Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Mealy Percent • Malt is characterized as mealy, half-glassy, and glassy. Mealy malt is very chewable, whereas, glassy malt is very hard. • Well modified malt is mealy. • For infusion mashing, the malt should be at least 95% mealy. Malt should be at least 92% mealy for decoction and step mashes. Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Malt Analysis Example Let’s review a typical malt analysis from Briess Malt and Ingredients Co. http://www.briess.com/brew/products.shtml Provided by Ken Woodson & the North Texas Home Brewers Association Beer Strength • Most accurate (but time-consuming) method would be distillation and measurement of alcohol content • Instead, Density is usualy used as an approximation • Specific Gravity: density relative to pure water • Water is 1.000, pure alcohol is 0.789 Beer Strength • Original Gravity (OG) is specific gravity BEFORE fermentation (also called original extract) • Final Gravity (FG) is specific gravity AFTER fermentation • ABV% ≈ (105 x (OG-FG)) / (0.79 x FG) Beer Strength • Many systems for measurement of density: points, brix, degrees Plato, etc • Points is simply the thousands of a specific gravity: SG 1.020 = 20 points • British Brewers often use degrees Plato, which is roughly: points / 4 (so SG 1.020 ≈ 5 degrees Plato) Beer Styles • The idea of distinct, recognizable styles is mostly a modern invention (1977+), but has become big business • Style can include measurables such as color, flavor, strength, but also includes intangibles such as production method, history, or country of origin Beer Styles • Divided traditionally between Ale and Lager styles Types of Beer • Ales – Use “top-fermenting” yeast which is unable to metabolize certain sugars. This results in a fruitier, sweeter beer. Top fermenting yeast rises to the top of the vessel during fermentation. – Fermented at higher temperatures than lager beer (15–23°C ) – Ale yeasts at these temperatures produce significant amounts of esters resulting in a flowery, fruity aroma • Pale ale – Brewed using a pale barley malt. Hop levels can vary. • Dark ale – Brewed using dark roasted barley malts. Also called stout. • Irish red ale – The red colour comes from the use of roasted barley. Has a malty, caramel flavour. • Cream ale – Brewed to be light in colour, hop and malt flavour is subdued. • Brown ale – Brewed with a darker barley malt, lightly hopped and fairly mildly flavoured with a slightly nutty taste. Ale Styles Top Fermenting Wheat Beers Pure Yeast Belgian Witbier/ White/ Blanche South German Weissbier/ Weizen Lactic Fermentation Berliner Weisse Sweet Stout Spontaneous Fermentation Lambic Porter Ale Types Oatmeal Stout American Ale Dry Stout Cream Ale Imperial Stout Pale Mild Dark Mild Bitter Best Bitter Light Ale Pale Ale Strong Bitter Gueuze So English Brown Ale No English Brown Ale Old Ale Pale/Dark Barley Wine Faro DunkelWeizen Kriek Irish Red Ale Strong Scotch Ale Belgian Brown/”Red” India Pale Ale Belgian Ales Altbier Weizenbock Frambooise American Hefeweizen Other Fruit Beers Saisons Trappisten Types of Beer • Lager – The most commonly consumed style – Fermentation occurs at around 7-12°C using a “bottom fermenting” yeast • “Fermentation phase” – Then cooled at 0-4°C • “Lagering phase” • The lager clears and mellows • Inhibits the production of esters, resulting in a “crisper” (less fruity) tasting beer – Has more fizz than ale – Premium Lager? No such thing. Lager Styles Bottom Fermenting Vienna Type Lager Pilsener Dortmunder/ Export Strong Lager American Malt Liquor Marzen/ Oktoberfest Munich Type Pale Dark Pale Bock Rauchbier Pale/Dark Double Bock Dark Bock