Hypertext with Characters Conversations with Friends Mark Bernstein

advertisement

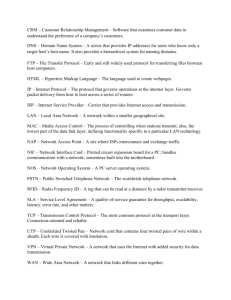

Hypertext with Characters Conversations with Friends Mark Bernstein abstract Most current hypertexts appear to the reader as a single entity, a written work that speaks with a single voice and presents a single viewpoint. Large and challenging hypertexts, whether technical, scholarly, or fictional, might benefit by introducing a dramatic multiplicity of voices and perspectives that engage the reader and each other. Characters are not merely names or pictures; to be credible and coherent, each character must be independent, persistent, and intentional. This paper proposes a framework for creating and discussing dramatic hypertexts in which separate characters participate fully and directly. The most interesting issues arise when characters are permitted to respond to other characters and to urge the reader to follow different trajectories through the hypertext. 1. Many Paths, One Voice The hypertext speaks with a single voice in "imagined conversation" between reader and creator. The authorial voice is explicit: when reading the hypertextual version of Jay Bolter's Writing Space, the reader knows that the ideas on the screen are Bolter's and that the process of exploring the hypertext is, in a sense, a dialogue with the writer. In George Landow's tour of his hypertext writing workshop, a unified authorial voice and organization mediate all the contradictory views and contrasting approaches the work presents. 1. Many Paths, One Voice In J. Yellowlees Douglas's I Have Said Nothing, the dialogue occurs between the reader and a fictional character. We know, as readers, that the narrator who begins: Remember Sherry? My brother Luke's piece: the one who got into that godawful tangle with him at Paycheck's in Hamtramck. is not actually Professor Douglas, but while we read the hypertext, our imaginary dialogue with the imagined character is exactly as real as the dialogue with Bolter or Kolb. 1. Many Paths, One Voice Familiar print forms share it: The essay: closely tied to the lecture, just as print fiction descends from storytelling and print poetry descends from recitation and song. In drama: each character as a separate voice. In a scientific workshop, a television talk show, or a political debate: from the drama of distinct voices, with the attendant possibilities of education, disagreement, conflict and resolution. 1. Many Paths, One Voice How might we create hypertexts that speak with the voices of many credible and engaging characters? Multimedia answer: To emulate the immersive qualities of performance by including video, animation, and sound. As an alternative to the intrinsic tension between links and pizzaz, I propose hypertext rich in character. 2. Hypertext Characters Characters are independent, persistent, and intentional. What is an independent character? a distinct and recognizable abstract unit, represented to the reader through a distinct and recognizable interface. Readers should be able to distinguish Hamlet from Horatio. HAMLET ACT I. SCENE IV. A PLATFORM BEFORE THE CASTLE OF ELSINEUR. HAMLET, HORATIO, MARCELLUS, AND THE GHOST. Hamlet. IT wafts me still:—Go on, I'll follow thee. Mar. You shall not go, my lord. Ham. Hold off your hand. Hor. Be rul'd, you shall not go. Ham. My fate cries out, And makes each petty artery in this body As hardy as the Nemean lion's nerve.— [Ghost beckons. Still am I call'd;— unhand me, gentlemen; [Breaking from them. By heaven, I'll make a ghost of him that lets me: I say, away:—Go on, I'll follow thee. Painted by Henry Fuseli, R. A. Engraved by Robert Thew. HAMLET One easy way to establish independence in a hypertext is to have each character's text (and other media) appear in its own pane. 2. Hypertext Characters What is a persistent character? to possess a continuous existence, even when the character is not the center of attention. Though Horatio is not on stage, we assume that he continues to exist. Moreover, persistence implies the ability to retain state; if something happens in the hypertext that affects Horatio, the effect should persist even when Horatio leaves the stage. 2. Hypertext Characters Tools like a Search dialog, on the other hand, may be independent but usually are not persistent. 2. Hypertext Characters What is an intentional character? To possess intrinsic behaviors which seems to serve some purpose or goal. The goal may be simple or complex, or not even be internally consistent; people, after all, are hard to understand. Internal rhetorical and stylistic consistency make characters seem intentional and therefore real. 2. Hypertext Characters Envision a hypertext: different characters appear as distinct hypertextual units. Characters might be implemented as separate hypertexts that interact with each other, or as distinct types or aggregates within a single work. 3. Conversations On Serious Matters The utility of characters in fiction is clear, but their relevance to technical and scholarly writing may seem far-fetched. Let us consider, then, how writing with characters might strengthen conventional technical project - writing a computer language tutorial for a professional audience. Let us describe one snapshot of this multicharacter tutorial in action. The topic at hand is the C++ auto-increment operator. 4. Implementation: Staying In Character Characters might be represented by placing their texts in different portions of the screen. This is a convenient spatial metaphor, establishing a connection between location and role. What is GOOD about it? 1) Because the notional voices occupy disjoint spaces, readers perceive them as distinct. 2) Because the visible manifestation of each character - its window - remains constantly in view, it is easy to establish temporal coherence. 4. Implementation: Staying In Character What is BAD? Dividing the screen among many characters may leave each character with too little space. The placement of each character on the screen necessarily reflects a judgment of the centrality of each character. The unchanging placement of characters is fundamentally undramatic. 4. Implementation: Staying In Character Suggestions: Retain spatial relationships and improve the screen layout by specifying constraints rather than actual placements. When we follow a link, each character's representation might change size and position as needed to satisfy its constraints. 4. Implementation: Staying In Character Include a portrait of the character within each of its nodes. Establish character through typographic convention, associating different characters with different textual appearances. For example, one type face indicates the central narrative while a different face distinguishes a melange of nightmares and refracted images thrown off by the central story. 4. Implementation: Staying In Character 5. Characters Responding to Characters More hypertextual structures arise when characters respond not merely to the stimulus of a central hypertext, but also to each other. A range of fascinating and pathological behaviors becomes possible. For example, consider a work in Roman history that includes (among other characters) a Marxist Historian and a Glossary. 5. Characters Responding to Characters “Plebiscitum“ = an enactment of the Roman popular assembly. The Marxist Historian responds to this definition, perhaps to illustrate a nascent sense of "class" in the ancient term. In so doing, the Marxist offers the Glossary a new opportunity to define "plebiscitum", to which the Marxist again responds. A succession of dense and vehement screens flies before our eyes. 5. Characters Responding to Characters The Trellis model: analytical tools needed to model these phenomena, and could allow the system to warn the writer of potential pathological interactions. 5. Characters Responding to Characters The reader as a moderator. When a character has a response to the current situation, it signals to the reader that it has something to say and waits for permission to proceed. By giving only one character at a time a chance to change the hypertext's state, we promote depth-first exploration. 5. Characters Responding to Characters Eager Links cause immediate transitions as soon as their preconditions are satisfied, and which should be written with care; Plain Links cause their character to ask for attention as soon as their preconditions are satisfied; Timid Links are identical to plain links unless the character is already seeking attention. In that case, plain links would change what the character wanted to say, while a timid link would merely add another option from which the reader could choose when giving the character her attention. 6. Advisors: suggesting What To Visit Next To create intentional characters that offer navigational advice. In this approach, each character participates in a hidden game based on the reader's trajectory through the hypertext. How? The rules are as follows: 6. Advisors: suggesting What To Visit Next Each character has a unique color. Characters seek to collect tokens of their own color, and ignore tokens of other colors. The author populates the hypertext with tokens of various colors and weights in selected nodes. Tokens are placed at nodes of particular interest to a the character. 6. Advisors: suggesting What To Visit Next When the reader visits a node, all the tokens from that node are distributed to the corresponding characters. Characters offer navigational advice, seeking to maximize value of the tokens they will have collected at the conclusion of the reading. A simple min-max search to fixed depth should prove sufficient for the hypertext system to calculate each player's recommendation. 6. Advisors: suggesting What To Visit Next A topical guide can easily be constructed by scattering its tokens at places most relevant to its concerns. Conversely, negative token weights let us construct a character that tries to steer the conversation away from sensitive subjects, a behavior not discussed in the hypertext literature but which has clear dramatic possibilities. By placing tokens uniformly throughout the hypertext, the writer can create a character that seeks out heavily textured areas.