DOCX 99.9 KB - Department of Transport, Planning and Local

advertisement

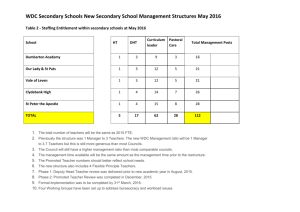

January 27, 2015 Interface Secretariat Level 4, 140 Bourke Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Mr Colin Morrison Executive Officer Victorian Grants Commission GPO Box 2392v Melbourne VIC 3001 via: colin.morrison@dpcd.vic.qov.au Dear Mr Morrison, On behalf of Interface Councils, I would like to thank you for meeting with us in December. Following our conversation we have reviewed our case and would like to present you with some of the key concerns of the Interface Councils group in relation to the Victorian Grants Commission allocation process. As per your suggestion, we would like to arrange a time to meet with yourself, John Watson, Michael Ulbrick and Julie Eisenbise to discuss how we can move forward and achieve a more equitable distribution of grants for 2015/16. As a group of councils that comprise of high growth urban, regional and rural municipalities, we feel the allocation of grants in the past has not reflected the unique needs of our communities and this letter intends to provide you with an overview of the key reasons we believe the imbalance of grants funding needs to change. Over the past number of years the allocation of grants has been based on historical data that are retrospectively inaccurate. Over time, this has meant that the calculations that are made to distribute grants across the state have consistently underestimated the requirements of Interface Councils relative to other municipalities to deliver essential services and infrastructure for our communities. Unless this information is improved, the formula used to assess the relative needs of Interface Councils will continue to unequally distribute the grant funding and the under-allocation of funds will simply grow larger. It is important to note that this shortcoming is not based on an assessment of what is fair and not fair but based what we now know is misleading data. Additionally, the formula that is being used to distribute grants, written in 2001 is based on the number of dwellings within a council’s boundaries rather than on the number of people that live in the area. This methodology does not reflect the reality that the household size is often greater in outer suburban areas compared to inner metropolitan Melbourne. For example the average number of persons living in one dwelling in the City of Yarra in 2011 was 2.15 compared to the City of Melton at 2.90. Interface Councils believe that is crucial that this formula is re-assessed to accurately assess the need of all councils. The above matters have placed Interface councils in a poor position to meet the needs of their communities. From the allocations that we have received, the focus of the Victorian Grants Commission has solely been on recurrent spending requirements rather than capital necessities. In rapidly growing communities such as ours, there is a relentless need to build, upgrade and maintain the capital that comes with growth, yet this is rarely recognised in grant allocations. City of Casey Cardinia Shire Council Hume City Council Melton City Council Mornington Peninsula Shire Council Mitchell Shire Council Nillumbik Shire Council Whittlesea City Council Wyndham City Council Yarra Ranges Shire Council The consequences of these issues include dramatically underfunded Precinct Structural Plans in Interface Councils to the tune of $1 billion. It is important to note that those plans have been approved by the State Government. Precinct Structural Plans have provided our councils with the confidence that our rapidly growing populations will be met with adequate infrastructure and services, however, the capital funding allocated to support these plans is not met. As a result communities in growth councils have significantly reduced access to basic living necessities such as roads, schools and hospitals. Furthermore, while Interface Councils are 10 per cent urban and 90 per cent rural and accommodated 46 per cent of the state’s population growth from 2008-2013 they are often ineligible for grant programs specifically targeted to assist rural and regional councils such as the Regional Growth Fund. It is for this reason that the culmination of years of under-allocation for Interface Councils has significantly disadvantaged our ability to develop and maintain liveable communities. The importance and immediacy of this issue is heightened by the impending rate capping legislation that the Victorian Government are intending on implementing. It will significantly increase the pressure that Interface councils are already bearing as a result of underfunding and under allocation of government. Without recognition of the unique characteristics of Interface municipalities, the capacity for our councils to fulfil our function is considerably reduced. We understand and acknowledge the distribution of grants must be fair and meet the needs of 79 councils across Victoria, and therefore would greatly appreciate the opportunity to discuss the issues we are facing and how we can collaborate on ensuring that the process of allocation is fair for all of Victoria in 2015/16. Our secretariat will be in contact in the near future to arrange a time that is suitable to meet. If in the meantime you have any questions contact David Hawkins on 8317 0111 or via davidh@socom.com.au. Yours sincerely, Garry McQuillan CEO, Cardinia Shire Council Interface Councils City of Casey Cardinia Shire Council Hume City Council Melton City Council Mornington Peninsula Shire Council Mitchell Shire Council Nillumbik Shire Council Whittlesea City Council Wyndham City Council Yarra Ranges Shire Council Interface Councils Briefing paper for the Victorian Grants Commission March 2015 City of Casey Cardinia Shire Council Hume City Council Melton City Council Mornington Peninsula Shire Council Mitchell Shire Council Nillumbik Shire Council Whittlesea City Council Wyndham City Council Yarra Ranges Shire Council Introduction Interface Councils welcome the opportunity to provide a submission to the Victorian Grants Commission to outline in further detail our concerns regarding the grant allocation process which is contributing to the significant inequity facing Interface communities. The Interface acknowledges that the current fiscal situation in Victoria is extremely tight with revenue streams under pressure. Locally generated revenue has decreased and the amount of GST revenue from the Commonwealth has also been reduced. For its part local governments’ capacity to raise revenue is very limited, notwithstanding it has looked to maximise its funding sources as much as possible. This briefing paper intends to provide the Victorian Grants Commission with greater detail of the reasons Interface Councils feel a review of the grant allocation process is required. It does so by answering the following key questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. Why has past grant allocation not reflected the unique needs of Interface areas? What is the key issue with data used in the grant allocation process? How does the distribution of grants under estimate the requirements of Interface Councils? How has the grant allocation over the last three years disadvantaged Interface communities? Interface Councils conclude this briefing paper by stipulating the key aspects of the allocation methodology that should be revisited and some subsequent suggestions for changes to the formula that would ensure a fairer distribution of grants for all 79 states across Victoria. 2 1. Why has past grant allocation not reflected the unique needs of Interface Councils? Over the past decade Interface Councils have been responsible for 46 per cent of the state’s population growth and 53% of metropolitan Melbourne’s population growth. Although the grant allocation formula considers population growth as a factor in achieving an equitable distribution it does not consider some of the diverse and complex characteristics that Interface Councils possess, and when combined with rapid growth, creates greater financial pressures compared to non-Interface councils. Interface areas are 90 per cent rural yet 90 per cent of the population live in the 10 per cent of Interface areas that are urban Despite 90 per cent of Interface areas being rural, 90 per cent of the Interface population live in the 10 percent of Interface areas that are urban. This means that Interface Councils must service both large populations and significant areas with unique townships. This characteristic is not recognised by any of the population cost adjustors stipulated in the grant allocation process. Population density adjustor indicates that more concentrated populations may require greater council expenditure to service, for example, the waste management function is weighted 20 per cent by this cost adjustor. There is however, little evidence to support this. Interface Councils would suggest that there are in fact higher costs associated with servicing higher than average household sizes as is the case in Interface municipalities, despite these large households being dispersed across larger areas. The need to manage 90 per cent of Melbourne’s Green Wedges The non-urban green wedge areas located within Interface municipalities represent some of Melbourne’s most important assets in terms of the liveability, sustainability and prosperity of the entire Melbourne region. Yet, the Commission does not acknowledge the wider community benefit of Green Wedges, meaning the costs of preserving them becomes a financial burden that rests with Interface Councils. Interface Councils recognise that the Commission has recently incorporated an environmental risk adjustor which recognises the additional expenditure some councils face associated with flood mitigation, land erosion and fire control and management, however Green Wedges are neglected. It is important to note that Green Wedges encompass remnant vegetation, smaller areas of agricultural production and larger properties with very limited development potential under current planning legislation, which limits the capacity of Interface Councils to generate revenue. Commercial/Industrial land Interface Councils rely predominantly on residential rates, with only a small proportion of industrial and/or commercial properties and activities (e.g. parking) to generate revenue. Consequently, the ability of Interface Councils to raise revenue compared to other metropolitan councils is significantly reduced and keeps the rating burden on residential properties. Ineligibility for other grants Due to the geographical makeup of Interface Councils, grant programs that specifically target regional and rural municipalities such as the previous government’s Regional Growth Fund are inaccessible. This ineligibility compounds the ongoing underfunding of critical infrastructure in government budgets. The lack of access to funding programs consequently means that Interface communities must bear the costs, through increased rates and/or reduced access to infrastructure and services, below that of the rest of Victoria. 3 2. What is the key issue with data used in the grant allocation process? The formula that establishes the distribution of grants across the state is backwards looking. There is a lag that means that rather than predicting the need for increased expenditure to implement infrastructure and services in advance, Interface Councils are always a year behind. Precinct Structure Plans, Strategic Resource plans, structure plans and other council strategies are vital to all councils to identify critical infrastructure and services to adequately fufil their local government function. The ability to implement projects that are identified as crucial to the liveability of communities in accordance and in advance of growth is fundamental to reducing the gap that already exists. It is imperative for Interface Councils that the Commission recognise the need for the formula to consider the future requirements of councils, particularly in respect to those that are the fastest growing municipalities in the state. 3. How has the distribution of grants across the state underestimated the requirements of Interface Councils? Recurrent expenditure to capital necessities With population growth comes a subsequent need to build, expand, upgrade and maintain capital infrastructure. However, the Victorian Grants Commission states: “Under the Commission's general purpose grants methodology, standardised expenditure is calculated for each council on the basis of nine expenditure functions. Between them, these expenditure functions include virtually all council recurrent expenditure.” Thus, the nine functions that calculate the standardised expenditure of councils do not reflect the need for capital necessities, which significantly underestimates the requirements of Interface Councils. Although several cost adjusters do account for several facets of growth as well as in relation to specific demographics, it does not account for the need to invest in new infrastructure to accommodate our rapidly growing populations. For example, the Commission recognises the increased recurrent expenditure associated with high populations under six years of age. However, it does not recognise that this adjustor becomes redundant if the existing infrastructure to provide the required services is at capacity. Similarily, although the standardised expenditure is adjusted if councils must cater for greater numbers of aged pensioners, being more likely to access council services, it does not consider the expenditure associated with the subsequent aged care and community facilities that are required to accommodate the higher ageing populations in Interface areas. Unfunded liabilities in Precinct Structure Plans Precinct structure planning is fundamental to making Victoria’s growth areas liveable, both today and in the future. PSPs lay out roads, shopping centres, schools, parks, housing, employment the connections to transport and generally resolve the complex issues of biodiversity, cultural heritage, infrastructure provision and council charges. The distribution of grants across the state underestimates the funding required in order to implement approved plans, and the fact that without implementation the functionality of these communities is significantly limited. As stated by The Parliamentary Inquiry in Liveability Options in the Outer Suburbs (December 2012): “By decreasing and delaying investment in infrastructure, an infrastructure gap is emerging that will significantly hurt the quality of life of people living and working in Melbourne’s outer suburbs.” 4 Table 1 in appendix 1 outlines the unfunded liabilities in the current precinct structure plans for Interface Councils, amounting to $779,273,468. When a PSP is approved by the Department and the Minister, it allows for development to occur, subject to a planning permit. Unfortunately, while a precinct becomes populated, the developers’ contribution and Council investment does not cover the amount required to construct all the essential infrastructure. Without State Government support, precincts are left without essential services and infrastructure. It should be noted that currently, developer contributions only cover approximately 25 per cent of the infrastructure costs incurred for new residents. An unintended consequence of the foreshadowed changes to the Development Contributions legislation will be a further reduction of the share of infrastructure costs paid for by Development Contributions with a greater share to be funded by ratepayers in general. Interface Councils are accommodating over 46 per cent of the state’s population growth, with which comes significant costs. The present system of local government funding, through rate revenue, developer contributions and one-off grants, fails address critical community infrastructure or services such as youth services, home and community care, maternal and child health and mental health. Impact of rate capping In addition, the impending rate capping legislation that the new government intends to enact this year will increase the pressure on Interface Councils’ ability to meet estimated recurrent expenditure, let alone their capacity to invest in capital necessities to accommodate the diverse and growing communities that define them, that are otherwise go unfunded. Rates are a key source of local government revenue and are in essence a tax based on asset value, rather than a direct fee for service. Nonetheless, for most Councils, and in particular Interface Councils, they represent the largest proportion of our budgets, and as a result there is a direct correlation between rating revenue generated and services and infrastructure delivered. Access to alternative sources of revenue is limited. An initial assessment of the impact of capping rates at CPI rather than at levels forecast in Strategic Resource Plans for Interface Councils indicates a loss of revenue of at least $220 million over the 4 years. 4. How has the grant allocation over the last three years disadvantaged Interface communities? Over the last decade the Interface has grown by 434,000 people whereas the rural and regional Councils have grown by 155,000. However, previously rural and regional Councils have received funding in the order of $1 billion over eight years to accommodate an anticipated population growth of 410,000 to 2036. Their growth equates to less than 20,000 people per year across all 42 rural/regional Councils. During that same timeframe the seven outer metropolitan growth area Councils, which form part of the broader Interface Group, will expand by 740,000 people. The underallocation of the General Purpose Financial Assistance Grants compounds an existing problem with government funding. The 2012/13, 2013/14 and 2014/15 budget scorecards prepared by Interface Councils demonstrate the significant gaps created by ongoing underfunding for Interface Councils’ infrastructure and services in government budgets. In 2014/15 there was an estimated shortfall of $810 million which proceeded a shortfall of approximately $895 million in 2013/14 and $955 million in 2012/13. Tables 2,3 and 4 in appendix 2 demonstrate the short falls within key infrastructure and servicing areas in real terms. 5 Disadvantaged communities The significant gap in funding from state government, combined with the underestimation of Interface Councils’ requirements has meant that Interface communities are disadvantaged on a number of indicators. The term "community disadvantage" represents a complex cluster of factors that make it difficult for people living in certain areas, such as the Interface, to achieve positive life outcomes and therefore make a positive and productive contribution to the community. The socio-economic profiling and benchmarking analysis in the “One Melbourne or Two?” report (Essential Economics, 2013) shows that compared to the Metropolitan Melbourne averages, the Interface Council area is characterised by: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Relatively high level of socio-economic disadvantage, as highlighted through SEIFA and VAMPIRE Relatively low average incomes Relatively low educational outcomes Evidence of poorer health outcomes Relatively high level of youth disengagement with regard to higher education and workforce participation Significant deficits in the provision of local employment opportunities Relatively low provision of professional jobs Relatively high unemployment rates Relatively low provision of higher order services (hospitals, TAFEs, Courts etc.) Relatively low provision of arts and cultural services (libraries, arts centres etc.) Poor provision of public transport options Heavy reliance on vehicle-based travel Community disadvantage emerges out of the interplay between the characteristics of the residents in a community (e.g., employment, education levels, drug and alcohol use) and, over and above this, the effects of the social and environmental context in which they exist (i.e., "place effects" or "neighbourhood effects", such as weak social networks, poor role models and a relative lack of opportunity) (Edwards, 2005; Vinson, 2007). 6 Recommendations for changes to the grants allocation process Ensure a more equitable distribution of funds based on needs Use population (instead of the number of dwellings) as the major cost driver for the waste management expenditure function – household numbers determine waste production, not property numbers. Reduce the level of the minimum grant – large metropolitan councils with access to other revenue sources (car parking fees etc.) with sizeable populations and able to achieve economies of scale have an automatic entitlement to the minimum grant – regardless of need. This reduces the pool of funds available to those councils with high need for funding assistance. Conclusion Interface Councils look forward to meeting with you to discuss the issues outlined in this paper on Wednesday 11 March, 2015. 7 Appendix 1- Precinct Structure Plan Liability Analysis - All Growth Area Councils Approved PSPs Council Cardinia Casey Hume Melton Mitchell Whittlesea Wyndham** PSP Name Cardinia Road Officer Cranbourne Fountain Gate Narre Warren Cranbourne East (DCP010) Cranbourne North Cranbourne West Clyde North Botanic Ridge Clyde Greenvale North Craigieburn Greenvale West Greenval Central Lockerbie* Merrifield West Melton North Taylors Hill West Toolern Diggers Rest Rockbank North Lockerbie* Lockerbie North Mernda-Doreen-Sth Morang Epping North Lockerbie* East Werrribee Employment Manor Lakes Truganina South Ballan Road Black Forest Road North Black Forest Road South Alfred Road Westbrook Quandong Bayview Oakbank Tarneit North Truganina Riverdale Total * PSP includes Hume, Whittlesea and Mitchell Councils ** The Wyndham data is currently confined solely to Community infrastructure 8 Total Unfunded Liability $27,467,942 $56,657,301 $20,000,000 $5,000,000 $8,918,761 $4,608,303 $3,270,420 $5,018,371 $7,848,330 $25,551,412 $6,771,000 $21,431,000 $3,901,000 $4,435,000 $65,690,000 $119,989,000 $12,295,121 $3,819,402 $7,790,872 $5,722,938 $18,710,114 $2,489,000 $16,208,964 $160,350,000 $104,650,000 $6,200,000 $1,103,494 $2,705,424 $1,485,650 $5,895,178 $5,454,813 $5,563,159 $990,931 $6,518,957 $1,752,624 $3,311,142 $4,838,886 $4,874,814 $4,916,051 $5,068,093 $779,273,468 Appendix 2: Disadvantage in funding for Interface Councils over the past three budget cylces Table 2: Budget Cyclical Interface Funding Estimates v Estimated Interface Requirements 2012/13 Est. 4-Year Funding Total Estimated Investment (1) Estimated 4- year Requirement (All funding sources) (2) Funding Surplus/ Deficit (All funding sources) Potential under provision (if required funding from all sources is not secured) TBC Early Childhood/ Kindegarten $9.2m $20.8m -$12.4m (note further annual grants are available over the 4-yeear cycle) Primary School $12.7m $180.4m -$167.7m 19,520/ 78 primary schools 2,220 places/3-4 secondary schools Secondary School/ all ages schools $76.6m $96.5m -$19.9m Special Education $27.8m $0 -$27.8m n/a TAFE $26.0m $94.8m -$68.8m 11,610 places/2 TAFE campuses Health $71.7m $288.3m -$216.6m 510 beds/6-7 hospitals $0 $405.6m -$405.6m 50 aged care facilities/3,000 beds $0.4m $5.2m -$4.8m (note further annual grants are available over the 4-yeear cycle) TBC $968.4m $1,440.0 -$471.60m Unable to cater for 9,320 new public service users $1,192.80m $1830.8m -$1334.80 Aged Care Library Public Transport Total Source: Victorian Budget Papers 2012/13; One Melbourne or Two – Implications of Population Growth for Infrastructure and Services in Interface Area, Essential Economics 2011 Table 3: Budget Cyclical Interface Funding Estimates v Estimated Interface Requirements 2013/14 Est. 4-Year Funding Total Estimated Investment (1) Estimated 4- year Requirement (All funding sources) (2) Funding Surplus/ Deficit (All funding sources) Potential under provision (if required funding from all sources is not secured) Early Childhood/ Kindegarten $14.2m $17.1m -$2.9m 340 places/3-4 buildings Primary School $22.5m $165.1m -$142.6m 16,740/ 67 primary schools Secondary School $29.4m $132.3m -$102.9m 10,380 places/20 secondary schools Further Education $26.0m $97.1m -$71.1m 11,990 places/2-3 TAFE campuses Health $113.2m $291.5m -$178.3m 420 beds/4-5 hospitals Public Transport $732.8m $1,127.7m -$394.9m Unable to cater for 8,010 new public service users Total $938.1m $1830.8m - $892.7m – Source: Victorian Budget Papers 2013/14, Children’s Facilities Capital Program Recipients 2012/13; (2) One Melbourne or Two – Implications of Population Growth for Infrastructure and Services in Interface Area, Essential Economics 2012. 9 Table 4: Budget Clclical Interface Funding Estimates v Estimated Inteface Requirements 2014/15 Est. 4-Year Funding Total Estimated Investment (1) Estimated 4- year Requirement (All funding sources) (2) Funding Surplus/ Deficit (All funding sources) Potential under provision (if required funding from all sources is not secured) Early Childhood/ Kindegarten $14.2m $17.1m -$2.9m 340 places/3-4 buildings Primary School $194.3m $165.1m +29.2m Adequately funded over this 4 year cycle Secondary School $82.4m $132.3m -$49.9m 5,040 places/10 secondary schools Further Education $20.8m $97.1m -$76.3m 12,870 places/3 TAFE campuses Health $26.0m $291.5m -$265.5m 625 beds/5 hospitals Public Transport Total $683.5m $1,127.7m -$444.2m Unable to cater for 9,010 new public service users $1,021.2m $1830.8m -$809.6m – Source: (1) Victorian Budget Papers 2014/15, Children’s Facilities Capital Program Recipients 2012/13; (2) One Melbourne or Two – Implications of Population Growth for Infrastructure and Services in Interface Area, Essential Economics 2012. 10