History 3 Research Paper - Kansas State University

advertisement

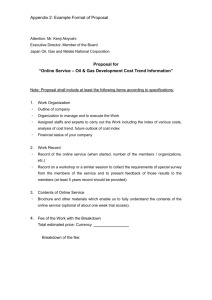

Introduction Jazz has always been seen as a male dominated musical genre, from Louis Armstrong to Benny Goodman to Charles Mingus. But Jazz has a spotlight on one Jazz musician and composer, Toshiko Akiyoshi. She is considered one of the first people from Japanese descent to have caused a ripple effect in the jazz world during the mid to late 1900s. Akiyoshi is one of the first females to dare go into a field that dominated by men and had to hurdle many obstacles from people who believed that she wouldn’t last1. Starting with be-bop jazz to her big bands ensembles, Akiyoshi has made an impact that no other man has made. In this paper I will discuss Toshiko Akiyoshi’s personal and musical background and two specific compositions Akiyoshi composed. Background and Career Toshiko Akiyoshi was born on December 12, 1929 in Darien, Manchuria, during a time when it was still under Japanese rule2. During the young years of her life, Akiyoshi’s family were financially stable with her fathers who owned textile company and a steel mill. During this time she remembers that although she lived in China, her life has always been Japanese. “There were separation between the Japanese and Chinese communities,” she says. “There were Japanese schools, Japanese stores and a Japanese hospital. I can’t remember any Chinese students, but in high school, my piano teacher was Chinese”3. Louis A. Lozzi, “Toshiko Akiyoshi,” Jazz Player 6 (1999): 31-39; see p. 31. Kevin Fellezs, “Deracinated Flower: Toshiko Akiyoshi’s ‘Trace in Jazz History,’ Jazz Perspectives 4 (2010): 35-57, 23p; see p. 39. 3 Michael Bourne, “Rising Hope,” Downbeat 70 (2003), pp. 44-47; see p. 44. 1 2 1 She was the youngest of four girls and had no brothers, which may have led her father to want her to be successful as a doctor when she grew older. But in her upper-class education expectations, girls were expected to learn Western classical music. Which led Toshiko to fall in love with the piano at age seven4. This made her the only person in her family who was not influenced by Japanese music during her upbringing. “My sister was a student of traditional Japanese dance,” Akiyoshi says in an interview. “My father was a student of noh (Japanese classical theater”). I heard Japanese music in the house, but in the Japanese schools, we never heard Japanese music. My musical education was always Western”5. When World War II ended, her family had lost their business and possessions, and was forced to move due to political and economic disenfranchisement of Japanese people. The Akiyoshi family travelled to Japan in late 1948, with expected plans that Toshiko would be attending medical school and with her hidden dream of still wanting to perform the piano. It became a difficult task to practice because of her family not having the luxury of having a piano. With the dire need to continue to play the piano, Akiyoshi comes across a help wanted position for a pianist in a dance hall that was for the occupation soldiers. She auditioned that day with an army dance band, and performed a Beethoven piano concerto for the manager. After the audition, she received the position right way and without know it, Akiyoshi started her musician career. Judith Lang Zaimont, Catherine Overhauser, and Jane Gottlieb, The Musical Woman: An International Perspective Volume II 1984-85 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1987), pp. 256-266; see p. 257. 5 Bourne, p. 44. 4 2 In this band, Toshiko develops a negative experience of jazz music. An exNavy orchestra leader led the ensemble, with violin, saxophone, accordion, drums, and piano6. In an interview taken Laura Koplewitz, Akiyoshi recalls her memory of the ensemble. “They were really bad!” says Akiyoshi. “We played from a ‘Hit Kit’ of basic arrangements of standard tunes, including some current popular music of the time. The book was published and distributed by the U.S. Military Special Services”7. From these arrangements, assumed that these were the fundamental sounds of jazz and that she had never heard real jazz because recordings were unavailable in Manchuria. A couple of the pieces that they performed were “Sweet Jenny Lee” and “Sweet Sue”, and at the time made her relate these pieces as “real” jazz music. She is quoted saying, “Boy did I hate it. All that mattered was that I could use the piano in the afternoon”8. Akiyoshi was finally exposed to genuine American jazz music when a record collector played several albums, such as Teddy Wilson’s “Sweet Lorraine”. From this exposure, she fell in love with the musical style and devoted herself to learn everything that she could, by copying the music from recordings and even tried to write down some of her own composition ideas. From the growth of wanting to know more about jazz music, she went against her family’s wishes and headed to Tokyo, which was one of Japans biggest jazz be-bop scenes of the time. While she was in Tokyo in the early 1950s, Akiyoshi she gained performance experience by playing in coffee-houses and playing in multiple ensembles such as Zaimont, p. 257 Zaimont, p. 257 8 Zaimont, p. 257 6 7 3 the Mori Orchestra, the Tokyo Jive Combo, Matsumoto and His Combo, the Blue Coats Orchestra, the Victor All Stars, and the Six Lemons9. Then in 1951, she started to create her own jazz combos. Like any musician who wants to get better at a specific style of music, Toshiko spent much of her time listening to some of the best artist of the time. Some of these individuals include Harry James, Gene Krupa, Teddy Wilson, and Bud Powell. From these musicians, Akiyoshi considered Powell to be one of the greatest influences she had early on in her career. Powell is known for his major contribution to the development of de-bop music in the United States during the 1940s. Akiyoshi’s piano style grew to have a “strong, sinewy right-hand capable of spinning out long melodic improvisations, accompanied in the left hand by light, sparse chord punctuations”10. With this technique, she was able to effectively play in a solo context or even in an accompaniment position in jazz combos very well. In 1953, jazz musician Oscar Peterson travels to Tokyo for the “Jazz at the Philharmonic” tour, which was managed by Norman Granz. While in Tokyo, he comes across Toshiko Akiyoshi playing the piano and stated her to be “the greatest female jazz pianist he had ever heard”11 and encouraged Granz to get Akiyoshi recorded. Later that year, she appears on Granz “Verve” label with Oscar Peterson’s rhythm section. When the album was released in the United States, it became an instant success12. Zaimont, p. 258. Zaimont, p.258. 11 Zaimont, p. 259. 12 Zaimont, p. 259. 9 10 4 During the next year, Akiyoshi is considered to be Japan’s leading jazz pianist and creates her own ensemble into an octet. At this time, she wants to develop more musically, so she starts to write and arrange her own music for her ensembles. Within the next few years, she becomes the highest paid jazz musician in Japan13. Akiyoshi wants to start expand more musically and geographically. She applies at the Berklee School of Music, which is known for their professional jazz curriculum. Berklee realized that this would bring media and recognition to the school, and was happy to accept her. Upon arriving to the school in 1956, she realized that she would gain a variety of new knowledge and a chance to improve her arranging skills, but was as a scholarship student she was restricted to Berklee for her three-and-a-half years of study. She led a jazz trio to clubs, such as Hickory House in Boston, under the sponsorships of the Berklee School of Music. This led to her receive much attention from the press and she started to appear on radio and television shows playing be-bop piano dressed in a traditional Japanese kimono14. Akiyoshi did not have an easy ride though with getting recognized and respected as a musician. Even though she was seen as an accomplished jazz composer, starting with her Granz-recording, she began to come across more of the views of people that saw her as an outsider to American jazz because she was both Japanese and a women, who were considered second class no matter what nationality or race. There were also another factor that started to make Akiyoshi from the spot light, and that is the when the rock n’ roll explosion starts to take place during the 13 14 Zaimont, pp. 259-260. Zaimont, p. 260. 5 late 1950s and early 1960s. Jazz was becoming more out of style leading into the 1970s. She left Berklee in 1959, believing that she could make it on her own as a musician, composer, and arranger. She fought to have audiences to see her like other musicians, no matter what the gender. But audiences did not necessarily agree with her ideal view. Many would even expect her to play “light patter-music and background music”15 just because she was a woman. Despite the obstacles she would run into with audiences, she was still able to play frequently with Charles Mingus and with her own quartet and trio. Even though Akiyoshi was going through some difficult times in her career, her personal life began to look up more. These were the years when she met Charlie Mariano, who was a saxophonist who developed a strong reputation during the 1950s performing with Stan Kenton and other16. They were married in 1959 and in August of 1964 they had a daughter named Michiru Mariano. They created the Toshiko-Mariano Quartet, where both musicians composed and contributed to their group’s repertoire, and they developed their sound mainly from Akiyoshi’s original compositions. When her marriage with Charlie Mariano ended in the mid-1960s, she realized that there was huge interest in her music back in Japan. She decided for the next few years to travel back and forth from New York and Japan. During these travels, she would perform with several Japanese symphony orchestras and in the 15 16 Zaimont, p. 261. Zaimont, p. 261. 6 United States was recognized as one of the top ten “Women of the Year” for her composition A Jazz Suite for String Orchestra in Mademoiselle Magazine17. For the next several years, Akiyoshi spends a majority of her time travelling Japan and Europe. She still continues to have the opportunity to compose for the Tokyo International Theater, the Swedish movie “The Platform”, and in the summer of 1964 performs in an international jazz festival with J. J. Johnson Sextet. By 1965, she starts to work in Reno, Nevada and Salt Lake City to teach summer jazz clinics. Also committing to the Japan Swing Journal in writing articles on a monthly basis18. Akiyoshi soon starts to become interested in composing for Big Band and then develops the goal to her own debut in New York City. For about a year, Akiyoshi would set aside a modest portion of what she earning from playing in clubs and lounges. Her ideal location in New York City was to perform in the Town Hall and the performance would include solo playing, trios, and premieres of new big band works as a grand finale. She looked to the Japanese community by spending days going door-to-door selling tickets. At the time she explained, “They will only buy if I come to them in person. I have spent many days going to businessmen and the nights working on my music. It is very tiring, but it must be done this way. Otherwise it is not proper.19” Her performance in Town Hall was in 1967 and developed to be a critical success. But came across some financial issues of rehearsing and performing with a big band. They were an issue because big bands had not been in its prime for about Zaimont, p. 261. Zaimont, pp. 261-262. 19 Zaimont, p. 262. 17 18 7 two decades by then and it limited Akiyoshi’s opinions in finding capable performers. With this turmoil, she almost considered to quitting music entirely, until she met Lew Tabackin. He realized that she could make major contributions to the genre and supported her to continue on composing and pushing ahead. They were married by 1969 and moved to Los Angeles to try to find more performance opportunities. In Los Angeles, Tabackin found a position in on Television’s “The Tonight Show” as one of Doc Severinsen’s Band members. Akiyoshi and Tabackin then created their own quartets that would perform in clubs in the Los Angeles area. They then came up with the idea of putting together a “workshop” situation with a big band that would rehearse weekly, never considering the idea of this being as a performing ensemble. Through this ensemble, Akiyoshi was able to compose and rehearse her big band compositions and even a year later decided to contract the band for performances. They found a small club in Pasadena for little to no money, and took home whatever was made at the door. Akiyoshi and Tabackin were able to putting together a concert that received full audience, but concert producers and club owners were still only interested in small, less expensive groups or were consider “all-star” bands. With the lack of support in the Los Angeles area, Akiyoshi turned to Japan and found enough interest there to help convince backers to invest and recording her band. With a small budget, they were able to get recording conditions in a small studio, where the album “Kogun” was recorded and first sent to Japan to be released. “The album became one of the biggest all-time jazz hits in Japan, selling an 8 immediate 30,000 copies when it first appeared and tens of thousands of additional copies to date”20. By the mid- 1970s, Akiyoshi was known to be a big band composer, arranger, and conductor. In 1976, she was recognized in multiple polls and nominations for her and her group’s accomplishments. Such as the Akiyoshi-Tabackin Big Band placed first in a down beat critics poll, the album Long Yellow Road was named best album of the year by Stereo Review Magazine, the album Insights was voted Jazz Album of the Year in Japan, and Akiyoshi has received six Grammy Award nominations since 1976 for her big band albums21. Akiyoshi continued to receive more recognition at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s. By 1978, down beats selected Insights as Record of the Year, in that same poll awarded first place to Toshiko Akiyoshi as a jazz arranger, and her big band was voted number one in the big jazz band category. For the first time in jazz history that a women had received top honors in down beat’s composer/arranger and big band categories22. And every year after that, Akiyoshi is repeatedly cited in magazine polls and earned more awards up into the early 1980s. Also in the late 1970s, Akiyoshi finally formed her own jazz recording label, called Ascent. Under this label, she was able to release three more albums, Salted Gingkos Nuts, European Memoirs, and Ten Gallon Shuffle. Her later recordings began Zaimont, p. 263. Zaimont, p. 263. 22 Zaimont, p. 263. 20 21 9 to feature her big band title solely on her own name, “Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra”23. Hiroshima: Rising From the Abyss To end World War II, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. This single act killed more than 60,000 and wounded another 70,000 people in the matter of minutes. And then the United States dropped the second bomb on Nagasaki, which ended the war24. On this day, Toshiko Akiyoshi was living in Manchuria and had no idea of the details of the destruction. She only knew that the war was finally over. “I was 15 when that happened,” Akiyoshi remembers, “but all I knew was that the war was ended. We knew that a bomb was dropped, but we didn’t know the effect. People at the time tried to avoid speaking about it. Even the victims didn’t want to talk about it”25. The next big moment for Akiyoshi to think about this event, is when a priest from Hiroshima asks her to compose a piece about that day. The priest sent some pictures of the event that were taken three days after the bombing, which makes these pictures some of the first views of the destruction that Akiyoshi has ever witnessed. “I have never been shocked that much in my life. The effectiveness of this bomb was indescribable. I thought, ‘I can’t write about this.’ I couldn’t see the reason or the meaning. But I was turning the pages, and on one page there was a young Zaimont, p. 263. Bourne, p. 44. 25 Bourne, p. 44 23 24 10 woman. She was in the underground, and she wasn’t affected. She came out, and she looked so beautiful. She’s got a little smile, a fantastic smile. And when I saw that, I said, ‘I can write that!’26. That was the beginning moments that created the idea for Toshiko Akiyoshi’s jazz piece Hiroshima: Rising From the Abyss. This piece has three movements, “Futility Tragedy”, “Survivors Tales”, and ends with a movement called “Hope”. In the first movement, “Futility Tragedy”, begins with Lew Tabackin, a saxophone player and several other soloists “swinging straightahead”27. The ensemble crazily improvises, which is recognized as the A-bomb and then the explosion that takes place when it hits the target. This leads to the second movement, “Survivors’ Tales”. In contrast to the first movement, this is a serene section that uses the Korean Flute. The flute trills represent “The haunting voice of the young women tells stories of Hiroshima’s mothers and the children they’ve lost. There are also voices created by the performers, which indicate “individuals walking from the rubble and talking with each other about what’s happened”28. “Hope” is the final movement of this piece. Taking a young woman’s thoughts on how life would never be able to return to Hiroshima. But is proven wrong when nature starts to show signs of life again despite the destruction. Also representing that we learn from our past and look forward to the future29. Bourne, p. 46. Bourne, p. 46. 28 Bourne, pp. 46-47. 29 Bourne, p. 47. 26 27 11 Kogun This composition is know to be inspired by a story about a Japanese soldier found hiding in the Philippines and is unaware that World War II has been over for about thirty years before30. Akiyoshi discovered that the translated meaning of kogun is “forlorn force” or one-man war, which means somebody who stands alone and fights31. Within this piece, Akiyoshi wanted to find a way to show off Lew Tabackin on the flute. “Since I didn’t have a flute feature for Lew, this seemed to be a fitting showcase for him. Lew is a master of cadenzas”32. Another unique sound that is used in this piece is the use of traditional tsuzumi drums of the Japanese Noh drama. “I was attracted by the sound because my father was a Noh player and a longtime student of Noh. It creates such a great sound and such a sense of time and space—I really felt I could utilize it well in conjunction with the traditional western big band swing”33. Akiyoshi had a challenge to get the tsuzumi drums into her compositions because there are no tsuzumi players in the Los Angeles area. To solve this issue, Akiyoshi simply took some tapes from Japan, and isolated the segments she wanted to use and put them in a sequence34. When asked if it was difficult to add the drums into Kogun, Akiyoshi has replied, Fellezs, p. 37. Toshiko Akiyoshi, Kugon, Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin Big Band (Mosaic Select, MS-033 Disc 1, 2008). See p. 2. 32 Akiyoshi, p. 2. 33 Akiyoshi, p. 2. 34 Akiyoshi, p. 2. 30 31 12 Of course it was difficult! The point is: if you’re just going to use it for the sake of using it, then that’s not hard. And it will come out that way: very superficial. But if you turn it into a blend, if you bind it all into one music…for example, one thing I like to say is, if you put sand inside a clam shell, you get a pearl. You just bother the shell a little, so it tries to integrate the sand being there… if you are infusing something into the music, a different element, it should become richer—that’s the important part. If you infuse and element and it just remains something else, that’s not what I’m trying to do.35 Within many of her compositions, Akiyoshi uses this general idea whenever she uses Japanese instruments. When listening several pieces, the listener can hear the unique sounds of Japanese instruments but they are not functioning merely as an exotic sound just to add to the piece. They are blended in with the regular jazz instruments to create a new kind of jazz with an interest twist. “Kogun” is an arrangement that is approximately seven minutes long is scored as “Oriental/Swing.” The piece starts off with a tsuzumi drummer “utters a throaty, guttural cry whose quavering tone creates an atmosphere of urgency and a sense of distant sorrow”36. The flute soon imitating the fluid, bending tones of the voice, while playing a simple melody. The wind instruments enter in soon after the flute, imitating and amplifying the tsuzumi player’s voice with downward glissando William Minor, Jazz Journeys to Japan: The Heart Within (Ann Arbor: Oxford University Press, 2000), 31-41. See pp. 37-38. 36 Zaimont, p. 264. 35 13 that fade into silence. As the ensemble builds in intensity, the familiar swing jazz begins to push forward. The ensemble punctuates melodic phrases and chordal breaks with the snappy articulations of upbeat swing37. This ends quickly with the flutes entrance returns, copying the breathy tones and bending notes of the tsuzumi players voice and the hollow tones of the his drum. The tempo picks back up and improvisatory lines of unison melodies among the winds and brasses become more embellished to the moment that the piece peaks, and this allows the flute to take a “shakuhachi”-style solo (shakuhachi is a Japanese Bamboo flute). To end the piece, the tzuzumi drummer reenters, with the voice quavering and brief cry. With the example below, is from the conclusion of “Kogun”. The glissandos on this page represent the imitation that the instruments try to copy from the tzuzumi drummer throaty, cry that is carried throughout the piece. Figure 1 Conclusion of “Kogun.” 38 37 38 Zaimont, p. 264. Zaimont, p. 265. 14 Conclusion From starting off in classical piano lessons at seven years old to the present day jazz sensation, Toshiko Akiyoshi has been a major female composer in the Jazz genre. She takes the style and adds her own feelings and cultural background to her pieces, which make it her stand out from the other composers of the time and connect the audience a different way. As true musician, she tries to tie in her emotions to her pieces and gets them to blend together. “The feeling is the main thing and the techniques come second. I’m interested in incidents that happen to individual people that catch my heart”39. Akiyoshi is true inspiration for future composers to look up to when wanting to find ways to incorporate themselves into their pieces. Judith Lang Zaimont, Catherine Overhauser, and Jane Gottlier, The Musical Women: International Perspectives 1983 (Westpor: Greenwood Press, 1984), p. 202. 39 15